As I said in the previous blog, ‘What is a Good Reader?’, reading at university is really different to reading at home, say for pleasure or for instruction.

So in this first blog, we’re going to begin by breaking down the most common kinds of texts that you will encounter at university. There’s actually heaps of different kinds of texts you might encounter, and not all of them are things you actually read. Yep, the word text really refers to material that we encounter to develop our understanding and knowledge of something, and this includes films, audio, art and all sorts! But for simplicity’s sake, let’s stick to what we actually read at uni!

Most commonly, what we read is broken up into two general categories: academic texts, and non-academic texts.

Academic Texts

Academic texts are those that are written by academics and researchers and are generally intended to be read for an academic audience – so other specialists and researchers in the discipline. These include peer review articles, which are found in academic journals, and books and edited collections by either one, or multiple academic authors. These are sources of information that are considered most appropriate in an academic environment. On FLO, you can access the Library World module which breaks down what reading in an academic context is all about too. I highly recommend it!

Journal articles

Being peer-reviewed means that a journal article must be read and accepted by a panel of other specialists before it can be published. This ensures that the research meets certain criteria. For example, does it follow standard structures, are the research aims, methods and results clear, do the methods seem appropriate and reproductible? It’s about ensuring that what gets published is of a high quality, and that we can trust the research and its findings. However, not all peer reviewed journals are equal – but I’ll get to that.

Academic Books

Academic books are the second main way that academics publish their research. They can be edited collections, containing chapters by different authors, or single authored books. They tend to be more common in disciplines such as the Humanities and Social Sciences.

While they are not necessarily peer reviewed in the same way articles are, they do go through a rigorous editing process by academic publishers. If you’re unsure if a book is academic or for a general audience, you can often tell by the publisher. Publishers like Cambridge University Press, Routledge or Elsevier are examples of academic publishing houses. You can google whether an imprint is academic or commercial.

Textbooks

Textbooks are a bit different to academic books. They are still published by academic publishers, but their target audience is students, and their purpose is to instruct and teach rather than share new research. This makes them much easier to understand. They explain concepts at an appropriate level, and scaffold information to demonstrate how concepts build upon one another.

However, while they do make things much easier to understand, textbooks are often not seen as academic texts in the same way as articles and academic books. They may not be considered appropriate evidence by your markers if you use them in your essays. This comes down to that whole instruction versus new research issue. Instead, use your textbooks as a starting point to understand difficult concepts, and then move into more complex articles and academic books for your research. Having said that, though, there are some assignments and disciplines where using textbooks is appropriate. If you’re unsure – just ask!

Why are these texts so hard?

The problem with academic texts is they are written for an audience of other academics – not for students (except for textbooks!). Their purpose is to share research findings and make original contributions to knowledge. For this reason, they are about very specific subjects, and take for granted that you, as a reader, are probably already familiar with the topic and what has come before it. This means they often do not explain concepts in depth or unpack complex ideas, and background information is usually given in the context of what research has been done before. This can make them tricky to follow.

Understanding that different types of texts will require different amounts of concentration, energy and time from us is really important in preparing to read well. These texts can be complex, particularly academic texts – journal articles, and academic book chapters.

But I also think it’s useful to remember to think about these often dense, very technical academic texts in the same way that we think about any kind of story.

After all, a story really is about communicating something. Stories, across all cultures, function as a way of sharing information, knowledge and experience. Academic texts may use very complex language, and be not quite as entertaining as other forms of storytelling, but they are still performing that essential function: they are all about sharing knowledge, information and experience. If we can figure out what the heart of that story is – what the authors really want us to learn – then it can make understanding the rest of the article much easier. So ask yourself: what do you think the take home message of this text might be? What do the author’s most want me to know?

But don’t worry, I’m going to break down academic texts, particularly journal articles, in an upcoming blog!

Dictionaries and Primers

There are some other kinds of books that can help us understand academic texts, and these are discipline specific primers and dictionaries.

These are designed to help unpack the technical language and concepts of your topics and break down often quite complex ideas into more easily digestible information. These can be an excellent place to start if you’re struggling to understand an idea in an article or academic book.

The Library Smart Search has guides by subject, so you can go in and see which dictionaries and primers your topic coordinators recommend. Check out the library Smart Guides here: http://flinders.libguides.com/?b=s.

Non-Academic Texts

There is a huge range of non-academic texts that you may be expected to read and to use as evidence in your time at university. Depending on what you’re studying, these can range from government and industry reports, to websites, to novels, plays and historical documents.

Grey Literature

Grey literature refers to documents and material that is published in non-commercial form. These can include government reports, policy statements, conference proceedings, geological surveys, fact sheets, maps, research reports, newsletters and more. These can often be your best sources of direct, up to date information about a certain subject.

Say for example you’re writing a paper about homelessness in Australia. The Australian Bureau of Statistics might have some of the best, most relevant data for you to use. Or, you might choose to check out a fact sheet released by a non-for-profit organisation. Both of these would be considered grey literature, and in the right context, can be very useful for your research. It is important to consider where this information comes from though. While many organisations are trustworthy, some might have an agenda!

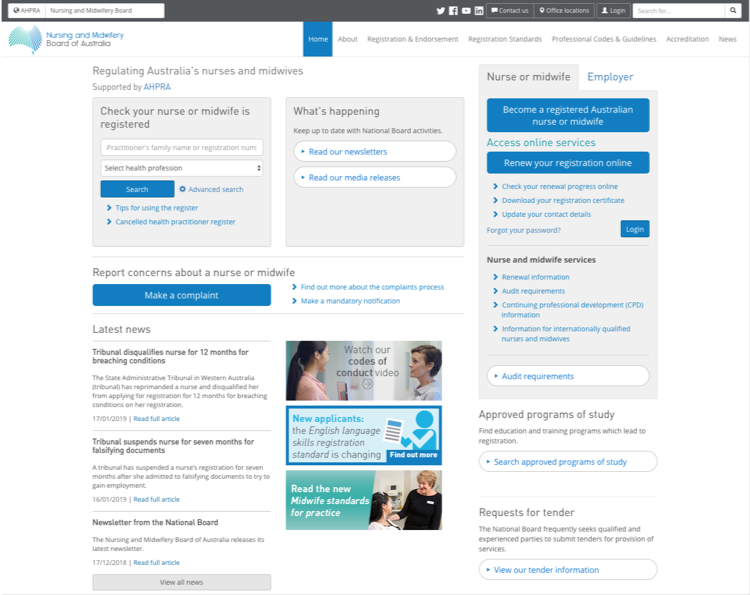

You can find a lot of grey literature through FindIt@Flinders and Google Scholar. However, you may need to broaden your search to find other kinds. This is where you can return to a normal Google search, particularly if you’re looking for government or organisational data. You will also become more familiar with the most trustworthy and frequently used organisations and websites in your field. For example, if you’re studying Nursing, you’ll probably use the Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia website to find policies, guidelines and fact sheets pretty often.

Primary Sources

Primary sources are immediate, first-hand accounts or documents. These can include newspaper reports, speeches, diaries, interviews, books, poems, survey data or statistics, photographs, and more. Primary texts present a subject in its most direct form, and it is often our job to analyse them to gain an understanding about something.

Different kinds of primary texts are used in different disciplines to varying degrees. If you’re studying English or Drama, you will use a lot of primary texts such as books, plays and even diaries and social media accounts. In History, you will read speeches and historical newspaper articles, or look at photographs, songs and old footage. In topics such as Psychology, you might be given some raw data to interpret and discuss. In the Sciences, you will often create your own primary data by conducting experiments.

In each of these cases, you will be expected to interpret and analyse the primary source yourself, or in conjunction with secondary sources. In topics like English and History, your ability to interpret and write about primary sources without relying on the interpretations of secondary authors will be really important!

Secondary sources, by contrast, are those that interpret and/or analyse the primary source. This is what most academic texts are – an analysis or discussion of primary material. These can include articles about research findings, analyses of laws or policies, reviews of plays, essays about novels or poems, or books or articles about particular subjects, historical periods, concepts, theories or genres.

Remember that at uni, you will encounter a variety of different types of texts. Some disciplines will really privilege academic texts such as journal articles, while others will have a broader scope, and allow you to draw from lots of different kinds of other sources. Check the guidelines for you topic and if you’re ever in doubt about whether something is appropriate, just ask.

Also, remember that these are the kinds of texts that are privileged in a university context. It doesn’t mean other texts aren’t important outside of the academy, and that other ways of sharing knowledge are not significant!

In the next blog, we’ll break down how to understand academic texts – how are they structured, and what are some strategies to help you understand them?

If you have any suggestions for future posts, please let me know! And, of course, if you’d like to contribute I’m super keen to hear from you!

And last of all, don’t forget to subscribe!