A newly described extinct family of giant wombat relatives, by UK and Australian researchers, has been made possible by a pioneering trip into outback South Australia in the 1970s.

The remains are so different from all other previously known extinct animals that it has been placed in a whole new family of marsupials.

Mukupirna – meaning “big bones” in the Dieri and Malyangapa Aboriginal languages – is described in a new paper published in Scientific Reports by an international team of palaeontologists who examined the fossil stored in the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

Experts from the American Museum of Natural History, UNSW Sydney, Salford University in the UK, Griffith University and Natural History Museum in London found the partial skull and most of the skeleton discovered originally in 1973 belonged to an animal more than four times the size of any living wombats today and may have weighed about 150kg.

An analysis of Mukupirna’s evolutionary relationships reveals that although it was most closely related to wombats, it is so different from all known wombats as well as other marsupials, that it had to be placed in its own unique family, Mukupirnidae.

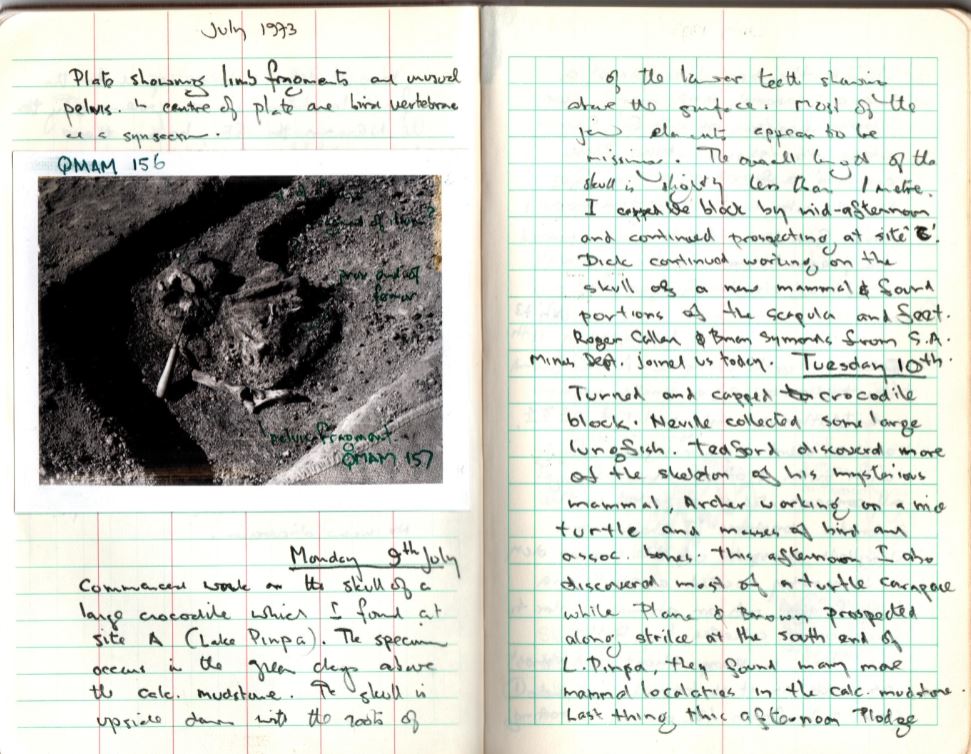

Veteran Flinders University palaeontologist Professor Rod Wells was part of an international exploration team led by the late Professor Dick Tedford from the American Museum of Natural History which found remains of the prehistoric, giant wombat-like marsupial – now named Mukupirna nambensis – embedded in the clay floor of Lake Pinpa, a remote dry salt lake east of the Flinders Ranges in South Australia.

Also on the original expedition was UNSW Science’s Professor Mike Archer who has helped describe the skeleton in a new paper.

He says their discovery of Mukupirna was in part due to good luck after an unusual change in local conditions exposed the 25 million-year-old fossil deposit on the floor of the dry salt lake.

“It was an extremely serendipitous discovery because in most years the surface of this dry lake is covered by sands blown or washed in from the surrounding hills,” he says.

“But because of rare environmental conditions prior to our arrival that year, the fossil-rich clay deposits were fully exposed to view. And this unexpected view was breathtaking.

“On the surface, and just below we found skulls, teeth, bones and in some cases, articulated skeletons of many new and exotic kinds of mammals. As well, there were the teeth of extinct lungfish, skeletons of bony fish and the bones of many kinds of water birds including flamingos and ducks.

“These animals ranged from tiny carnivorous marsupials about the size of a mouse right up to Mukupirna which was similar in size to a living black bear. It was an amazingly rich fossil deposit full of extinct animals that we’d never seen before.”

Professor Archer says when Mukupirna’s skeleton was first discovered just below the surface, nobody had any idea what kind of animal it was because it was solidly encased in clay.

Mukupirna is one of the best-preserved marsupials to have emerged from late Oligocene Australia (about 25 million years ago).

The scientists examined how body size has evolved in vombatiform marsupials – the taxonomic group that includes Mukupirna, wombats, koalas and their fossil relatives – and showed that body weights of 100 kg or more evolved at least six times over the last 25 million years. The largest known vombatiform marsupial was the relatively recent Diprotodon, which weighed over 2 tonnes and survived until at least 50,000 years ago.

The original party that discovered Mukupirna also included palaeontologists from the South Australian Museum (Neville Pledge), Queensland Museum (where Professor Archer was Curator of Fossil and Modern Mammals at the time) and the Australian Geological Survey Organisation (Mike Plane and Richard Brown).

Emeritus Professor Wells continues his research, as a co-author on a new paper ‘Variation in the sex ratio of pouch young and adult hairy-nosed wombats (Lasiorhinus latifrons and Lasiorhinus krefftii)’ by Matt Gaughwin, Alan Horsup, Christopher Dickman, Rod Wells, Faith Walker and David Taggart in Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology volume 74, Article number: 90 (2020).

Flinders University Palaeontology is working on analysing a large collection of fossils found in deposits in Lake Callabonna in the State’s Far North. The Flinders University Palaeontology Society met on Friday to discuss progress.