As the world anticipates the announcement of the 93rd Academy Awards on April 26, we spend a moment with Julia Erhart, Associate Professor of Screen and Media, to discuss her continuing studies into the roles of women in cinema – both in front of and behind the cameras.

What is your role and what does your work focus on?

I’m a feminist film scholar and internationally recognised researcher on women’s screen practice, including women’s interventions into the industries of independent and commercial feature filmmaking. For so many years, the film industry has been represented as a male dominated industry, however recently more and more female filmmakers are making an impact in the industry, and this has been recognised in the 2021 Oscars, with more women filmmakers nominated than ever before.

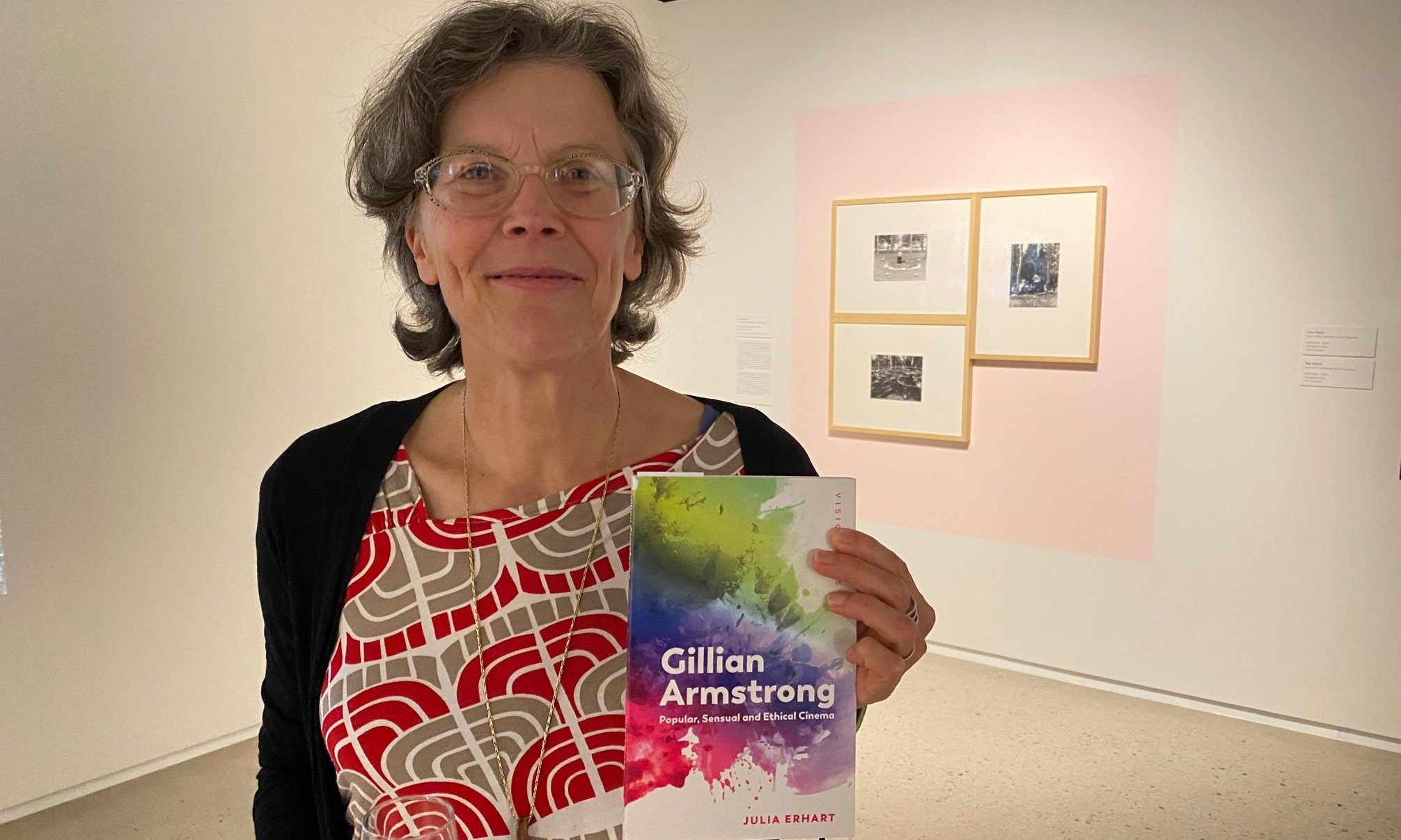

Examining what is changing in the industry fits in with the subject of books that I’ve had published – Gillian Armstrong: popular, sensual & ethical cinema (Edinburgh University Press, 2020) and Gendering History on Screen: Women Filmmakers and Historical Films (Library of Gender and Popular Culture, Bloomsbury/IB Tauris, 2018).

It’s an important and timely discussion. Variety, the specialist entertainment industry publication, estimates the global movie industry, which covers theatrical releases and home entertainment, is worth about $US100 billion. So having more women having leadership roles behind the camera in this industry comes down to a question of equity. Why should women accept being shut out of the decision-making end of an industry worth so much money?

The second important aspect of having more women leaders in film is getting the full story across. In Australia, screen entertainment has played a huge role in telling stories of great significance. If the industry only encourages males to take up the roles of directing and producing these movies, we are only hearing from half the population.

The growing numbers of female directors and producers also has an important trickle-down effect – if there are more stories about and by females, and more females being presented in front of the camera, there are also more females involved in technical or crew jobs. It’s a win for everybody.

In the 2020 Oscar nomination, there was no woman nominated in the best director category – Little Women directed by Greta Gerwig was nominated for Best Picture, but she didn’t receive an individual nomination.

While this year represents change that has brought about significant media attention and commentary – with the nomination of two female directors, Chloé Zhao and Emerald Fennell – things are not changing quickly enough across the industry. Luckily, we have community awareness and campaigns highlighting the imbalances in events such as the Oscars. These are applying pressure where it needs to be.

(For more about this subject, read Associate Professor Erhart’s article published in The Conversation: How the Oscars finally made it less lonely for women at the top of their game.)

All this is having an impact on the film industry – in Australia we are introducing our own policies through individual state film bodies, and it proves that movies about women and by women are definitely saleable. Look at the box office success of Wonder Woman. And women have such a high proportion of awards for per capita representation. So things are changing.

What journey brought you to this point in your career?

Film and television are formidable representation systems, and what we see on screen shapes our understanding of the world and our place in it. Filmmaking can both replicate and resist the status quo, and it’s very empowering to know this, whether you’re an arts student, an academic or an emerging filmmaker. This is something I’ve learned over the years through close study of less commercial media forms, like documentary, and this was reinforced when I did a brief stint working in the film industry in New York City.

Can you describe a challenge in your life and how you dealt with it?

I really felt enraged by the policies of the Trump administration and its war on facts, journalism and democracy. I’m lucky to teach in the arts, where we try to empower students to find their voice and explore the issues they’re most passionate about. The postgrad students in Screen are doing very important work and that’s always inspiring. I’m also a massive hazy IPA fan and that helps too!

What does a normal day look like for you?

Since last year I’ve been leading a pilot study exploring the workplace experiences of women workers in the “below-the-line” or technical sectors of the screen industries. This has been hugely rewarding and all-consuming; most days include contact with one of the team members to touch base, knot out issues in a paper we’re working on, and to discuss what’s next. My teaching numbers are high, so there are always lectures to prepare, assessments to mark and students to meet with.

What is something you are most proud of?

Professionally, I’m proud of the achievements of the Screen graduates; they are amazing. Personally, my two kids are truly thoughtful, creative, ethically minded humans. I’m proud of the family that my partner Susan and I have created.

How do you like to relax or spend your spare time?

My down time includes lots of contact with a network of family and friends in Adelaide, California, Minnesota and Texas, plus there’s dogs and chickens and gardening and a lot of reading non-fiction. I’m a runner, so if I can squeeze in a run, that’s a good day.