A decade of networking has led Flinders University graduate Dr Nicole (Nikki) Anderson back to Namibia as part of her work for the Kalahari African Wild Dog Conservation Trust (KAWDCT).

Her conservation efforts aim to highlight the importance of wild dogs in the Namibian ecosystem, and she continues to work with local farmers and communities to help save this critically endangered species.

Dr Anderson, who is now the KAWDCT’s research coordinator, says it’s estimated there are only about 6,500 wild dogs (Lycaon pictus) left in Africa and no more than about 300 wild dogs in Namibia.

“With an overall declining population trend their long-term future is precarious and depends on conservation efforts,” she says.

Her passion for the threatened species (also known as painted dogs) has also seen her work in the Animal Health Department at the Adelaide and Monarto zoos in South Australia, where she has also contributed to the Zoos Aquarium Association regional plan for carnivores for the African wild dog.

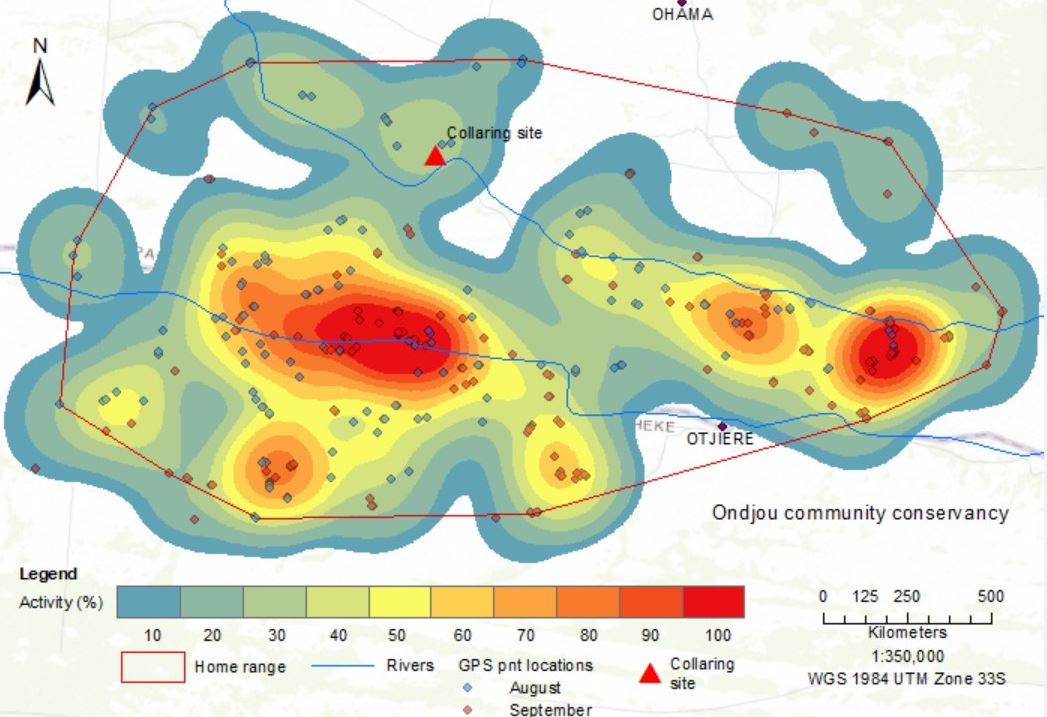

The latest field work in Namibia involved tagging and tracking two dogs with satellite radio collars to understand how wild dogs use the landscape.

“This is the first time wild dogs have been collared outside of protected areas and reserves in Namibia,” says Ms Anderson, who is also a casual academic at Flinders University.

“As is the case with many large carnivore species, there can be significant human-wildlife conflict that can affect long-term persistence.

“Information garnered from the satellite collars is initially being used as a first warning system for local farmers so they can kraal their livestock appropriately to minimise losses caused by predation.

“The information from the collars will also help to identify areas of high use and general territory size.”

In eight weeks after the collars were deployed in August, Dr Anderson has calculated the home range of this pack to be 1,177 square kilometres.

“While this is substantial, it does reflect the semi-arid environment and the low prey densities associated to the Kalahari biome,” she says.

“We are hoping to collar some additional packs in the very near future and complement this with a camera trap study to gain a better insight in the occupancy rates of other carnivores and, more importantly, the preferred prey species of the African wild dogs.”

Dr Anderson has previously been to Namibia, as well as South Africa, Zimbabwe and Zambia, to assist in conservation efforts on other wild dog projects.

Along with a Bachelor of Science (Biodiversity and Conversation) and Honours in Applied Geographic Information Systems, Dr Anderson’s PhD research examined vaccine efficacy in the African wild dog and how stressed they get during capture.

She hopes by better understanding how wild dogs behave in conjunction with giving landholders an ‘early warning’ system from tagged dogs, there will be a decrease in livestock predation and therefore incidents of human-wildlife conflict.

Along side community engagement and continual education, it is anticipated that “this can lead to greater acceptance of Namibia’s most threatened carnivore and hopefully an increase in numbers, which can then open up eco-tourism opportunities in local areas,” Dr Anderson says.