A feasibility and pilot study led by Flinders Caring Futures Institute researcher Professor Nicola Anstice and delivered through the University’s Health2Go clinic is investigating the efficacy of a dual-method pharmacological-contact lens management therapy for children with myopia.

Commonly known as short-sightedness, myopia normally develops between the ages of eight and thirteen. Often progressive into early adult years, the condition is irreversible. People with myopia report difficulty seeing objects in the distance.

“It develops because the eyeball has grown excessively long,” Professor Anstice explains. “So light focuses in front of the retina at the back of the eye rather than focusing on the retina itself.

“While it’s inconvenient for things to be blurry in the distance, the real issue is because the eyeball has grown too long, the retina becomes stretched. And so later in life, patients are two to 10 times more at risk of eye diseases like retinal detachment maculopathy, cataracts and glaucoma.”

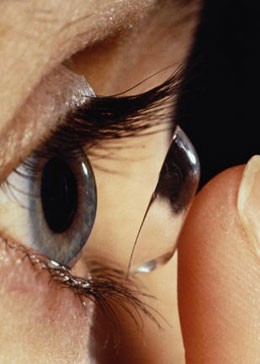

Traditionally, people with myopia have been given glasses to improve their vision, which need to be adjusted as the eyesight changes. Due to advancements in the management of myopia, a range of interventions are now available to slow the progress of the condition – including the use of specially-designed soft contact lenses.

A new project, funded in partnership with US-based contact lens provider Cooper Vision International, aims to establish whether wearing MiSightTM one-day disposable contact lenses during the day and applying low-dose atropine eyedrops at night can significantly slow the progression of myopia in children.

“We already know these lenses slow down myopia progression by about 50 per cent,” Professor Anstice says. “But if you add another method to that, with low dose atropine eyedrops in the evening, after you take the contact lenses out, do you get better efficacy?”

The research team led by Professor Anstice is recruiting children who have worsening myopia, and are comfortable wearing contacts lenses and using eyedrops, to find out.

“We’re trying to get them at the early stages of the condition, for two reasons,” she says.

“Firstly, because that’s when the progression tends to be the fastest. Secondly, every little incremental amount of increased myopia significantly increases the risk of eye disease later in life. So there’s no safe level of myopia. The lower we can keep it, the better we are long term.”

The participants will be randomised into three groups, with eye focus and eye size measured at three stages of the six-month study. These consultations will take place at Flinders’ Health2Go clinic, with students involved in the research.

“As part of the study, we’ve purchased special equipment that actually allows you to measure eye focus when children look in the distance. But you can also use it to measure how much they focus on close work as well,” Professor Anstice says.

“There’s that teaching and research Nexus going on, with our Optometry students helping out. This also makes what we’re doing translatable to clinical practice.”

The team hopes the intervention will halt the growth of the eyeball over the six month period, to reduce the likelihood of complications later in life. Professor Anstice says her team will also be measuring the daily variation in pupil size between the different groups of participants.

“We bought a special infrared camera that takes multiple measurements in about a three second period, and actually gives you a quantitative measure of the size of someone’s pupil.”

If successful, a longer-term trial may be conducted in the future.

“We’d like to recruit more participants to measure long term, over two or three years, whether this is a feasible treatment that we can use, in terms both of acceptability to patients, and also increased efficacy.”

The study complements an existing service led by the Flinders Optometry team, where community-based optometrists who don’t have the necessary equipment to manage myopia refer patients to the Health2Go clinic. The service gives Flinders students the opportunity to apply different theories and management options to these patients under the supervision of professionals, delivering a real-world experience before they enter the workforce.

Fellow Flinders researcher Dr Ranjay Chakraborty joins Professor Anstice on the study, with other research sites running at the University of Canberra and University of New South Wales.