Fresh off a plane from the UK, Dr Matthew Firth has been spending his days consulting with texts dating back to the 10th century. We spoke to Matthew after his return, where he debunked one common myth about the Middle Ages, and shared about the distinctiveness of the manuscripts he studies.

What is your role at Flinders?

For the past two years I have been an Associate Lecturer in the College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, working alongside Associate Professor Erin Sebo on her ARC discovery project: The First English Speakers in their own Words. In this role, I’ve been topic-coordinating English coded topics in medieval literature and history. My favourite is ENGL3115 Medieval and Renaissance Women’s Literature and Lives as it’s closest to one of my research specialisations – medieval queenship – and it also gives me the opportunity to step outside of western Europe to look at notable medieval women from eastern Europe, Byzantium, China and Japan. I’ve also been doing research work as part of the role, examining the corpus of texts in Old English – think the language of Beowulf – and cataloguing the expressions they contain of attitudes toward a whole host of subjects.

But, that’s all about to change! On 10 March I start as an ARC DECRA fellow on my project, Contesting Conquests: Pre-Modern Attempts to Come to Terms with the Past. So, for the next three years, I’ll be looking at medieval and early modern English history writing, examining how the history of England’s medieval conquests was constructed and transmitted over time. The project’s aim is to transform our understanding of how societies experience and remember the trauma of conquest and colonisation.

Tell us a little about how you got here.

I’ve taken the scenic route to academia. I was at University of Sydney doing a BA in the early 2000s. I started out doing languages but ended up with a major in Studies of Religion! I had intended to go on to a master’s degree, but life got in the way as it does on occasion. I wound up working in a bank in Sydney for almost a decade as a data analyst (among other roles). Then, in 2011, I had a tree change and ran a small gardening business in Hobart for eight years. I’m onto my third career (hopefully the last one!).

While we were living in Hobart, I picked up that long-neglected master’s degree and did a Master of History with the University of New England. I rather enjoyed it and proved rather good at it. Along the way, I met Dr Sebo at a conference and Brisbane and the rest is history! She convinced me to do my PhD with Flinders, I moved to Adelaide to do just that in 2019, graduated in 2023, and won a DECRA on my first attempt late last year.

What’s one thing people often get wrong about Middle Ages?

There could be lots of answers to this one: there was a greater awareness of hygiene than we often think, wider networks of trade, knowledge about distant parts of the world, and so on. But one of the things I often like to point to my students is how clumsy the terms ‘medieval’ and ‘Middle Ages’ are. It’s a period that covers a thousand years, from around 500AD to 1500AD. That means that we are currently closer to the end of the Middle Ages than the end of the Middle Ages was to its start. Most of us wouldn’t lump the year 2000 into the same cultural context as the year 1500. Similarly, it doesn’t make a great deal of sense to look at the Middle Ages as a singular period of time. If we then start to think about geographical breadth of places to which the term is applied, the cultural variety becomes immense. A lot of the things that are associated with the Middle Ages in popular imagination – feudalism, knights, plague, crusades, vikings – are quite specific to place and time. As a result, medievalists tend to be a rather specialised bunch. Personally, I focus on English and Scandinavian history from the ninth to eleventh centuries.

What’s your favourite fact to tell people about your area of work?

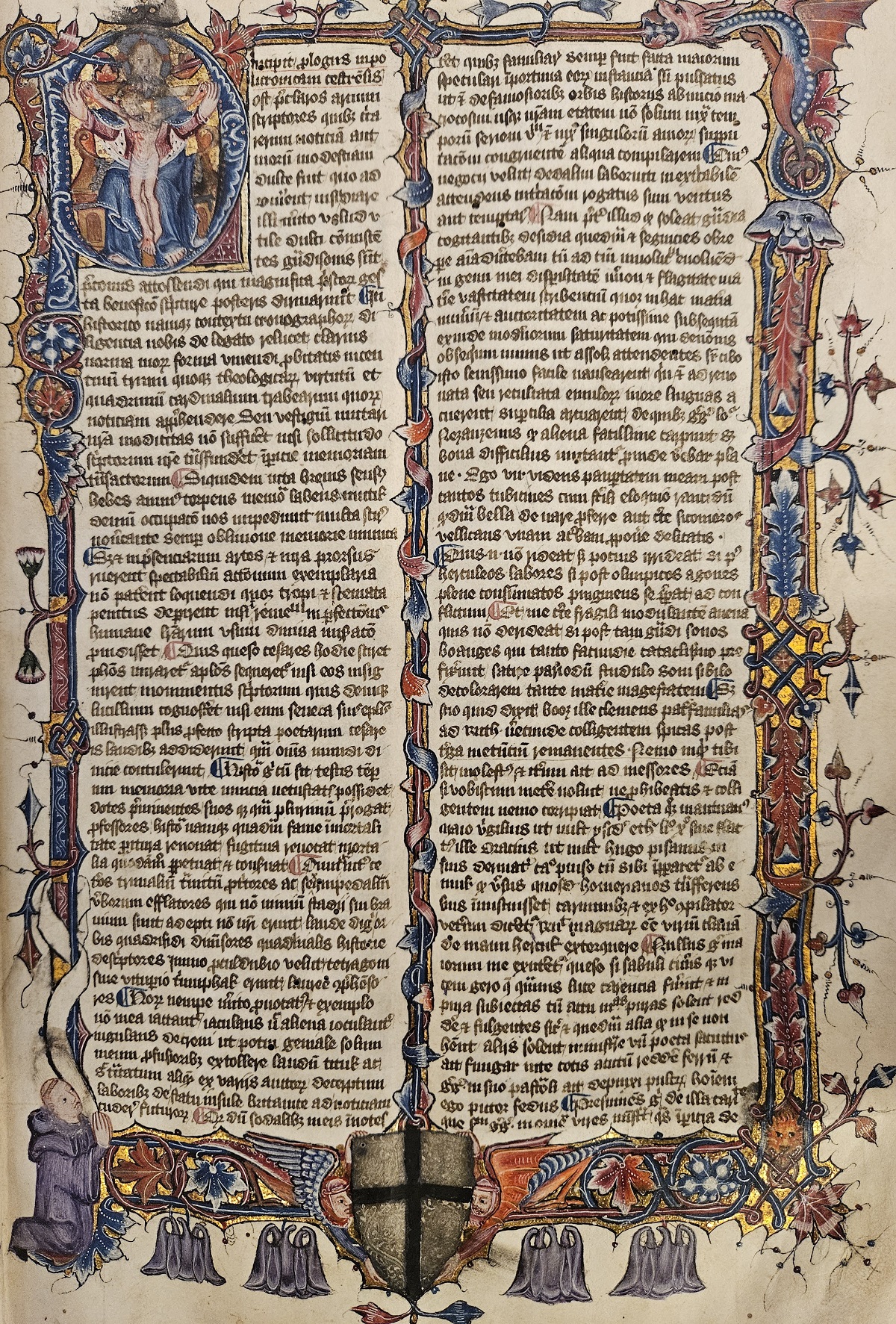

To some extent I answered this in the last question. I do like to draw attention to the sheer variety of life and culture in the Middle Ages across time and place. But probably the most important thing I need to tell people about for the context of my work is manuscripts. I work on a period of history before the advent of print in Europe. This means that I’m dealing with hand-written texts, usually in Latin. Some of these texts were quite popular. So recently I’ve been working through the extant editions of a text known as the Prose Brut – there are over 180 copies that survive. However, because they were all copied by hand, every copy is distinct. That can be as simple as layout or decoration, or it can be that a scribe adapted or abridged it, or even continued the history past where it originally ended. This means that researchers quite often have to go back to the manuscripts and compare editions to identify what is being said, the variations of it, and where those have crept it. It can be rather labour intensive. The flipside is that sometimes only one copy of text has survived into modernity, and these at times have been lost or destroyed by accident, leaving researchers to rely on transcripts or facsimiles.

There’s very little scholarship that is more useful to the wider community of medievalists than a modern, edited edition of a medieval text with original language and translation. It’s often work goes unrecognised outside of the field, but truly those who take on one of those labour-intensive tasks are doing the Lord’s work!

You’re currently in the UK as part of Australian Academy of the Humanities’ Travelling Fellowships – how is it?

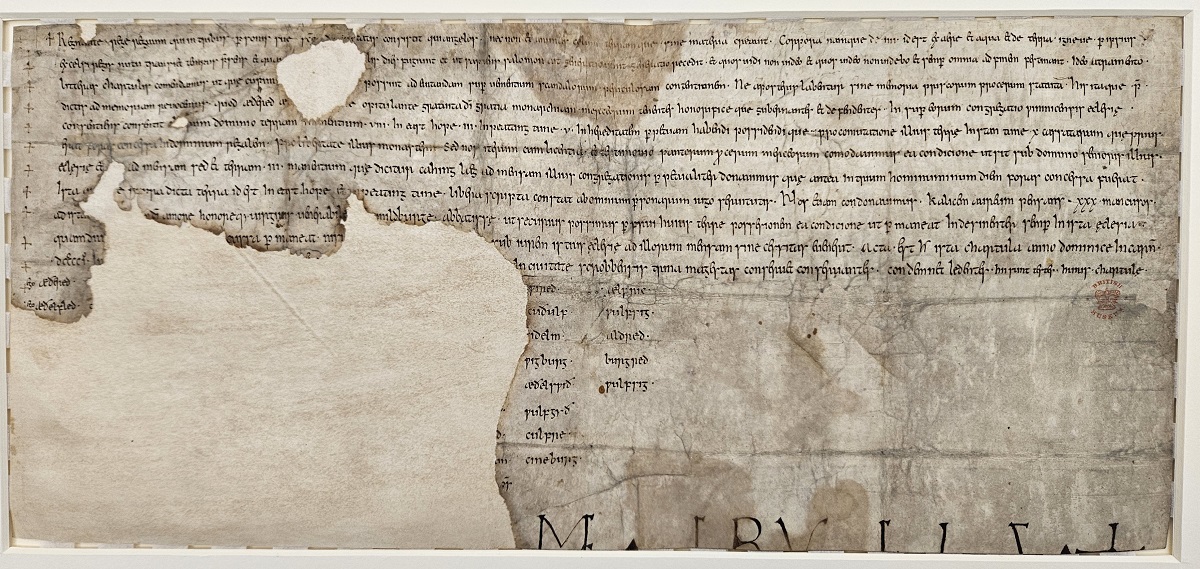

I’ve actually just made it home! I spent my time split between London and Oxford in the archives of the British and Bodleian libraries. I always enjoy being able to get my hands on pre-modern documents. The oldest one I consulted on this trip is a single-sheet charter held in the British Library. It was issued in 901 by Æthelflæd and Æthelred, the rulers of the English kingdom of Mercia. It’s the original document and records a grant of land to the church of Much Wenlock in modern Shropshire.

Mainly what I have been looking at, though, is chronicles – medieval historical texts. This does double time on both my ARC and AAH projects. The topic of my AAH research is life-writing: how were figures of England’s Anglo-Saxon history reimagined in the histories of later generations? So it’s a similar approach as I will be taking for my ARC project, just more narrowly focused. There are quite literally hundreds of manuscripts that I’m going to consult over the next few years, and all the images I’ve taken and transcriptions I’ve made on this trip give me a head start on both projects.

But to circle back around to the question: I’ve had a great time. I’m really confident that I’ve identified some very useful material, including two histories that have attracted very little commentary in modern scholarship. Now I just need to transcribe and translated them from Latin!

What are your favourite ways to pass your spare time?

What spare time!? I have a ten-year-old daughter, so much of what I have is spent with her. But I also keep tropical fish. It wasn’t something I ever intended to get into. My daughter asked for a small tank with three fish several years ago and somehow that’s turned into three tanks, 300l of water, fifty fish, hundreds of shrimp, and a large yellow snail named Kevin. It’s all surprisingly time consuming.