Reconciliation and Sorry Weeks at their most fundamental level call each of us to be reflexive (thinking, evaluating and acting) about our respectful relationships with others with a particular focus on those we hold with Aboriginal peoples. Marketing of this week challenges us to engage with the key ideas set out in the Uluru Statement and precursor texts such as the Yirrkala Bark Petitions, Barunga Statement, Redfern and Sorry speeches. Examples of these challenges, include questions about how we recognise and honour differing narratives of Australia’s settlement. Another question might interrogate how we can settle the hurts and pains of historic wrongdoing through ignorance of indigenous ways or through arrogance of not wanting to know. At a more basic level, we might be asked about our own personal engagements, views, and relationships with aboriginal people. In what ways do we know them in their diversity? For just like non-indigenous peoples, individuals describe themselves and know themselves in many ways.

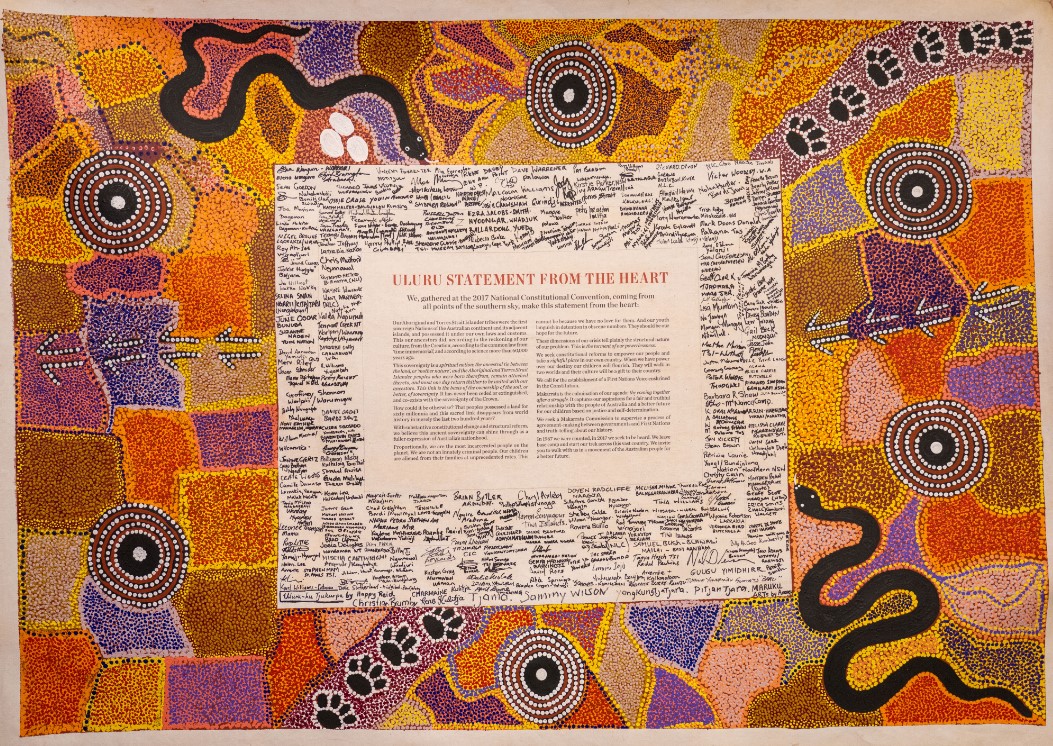

If we were to take the time to drill into some of these ideas a little more deeply, the marketing and ‘celebration’ of weeks that focus on reconciliation with or about others fails to challenge us to look at our own participation in these processes. The focus on appeasing others or being seen to do a right thing or ensuring that we say an agreed upon approach excuses us not to be accountable for our own capacity and capability for relationships. Nor do we take the time to really understand what key ideas of the Uluru Statement mean to us, in our personal and professional lives and how they are enacted through every relationship that we have. The Uluru Statement pillars: truth, treaty, voice and heart challenge us to reflect upon our ideologies but also about what we bring to our lifeworlds.

In the discourse of humanity, we proclaim that TRUTH is a quality and value we should all aspire, yet frequently in the professions, we are taught to couch the truth or to make it more palatable for the intended audience. In workplaces, the truth-teller or whistle blower becomes the pariah when they illustrate times when things are less than ideal. In the service-consumer model each participant makes conscious decisions about what needs to be known and at what time. There are many times for a doctor that the blood tests will not provide all the information that stories of life will add. The professions are increasingly positioned to know on behalf of another and make decisions accordingly. In turn, the agency of an individual is diminished, and truth is diluted or becomes something else.

In the same way, when we hear the word TREATY or MAKARRAṮA, we have flash back to understandings of mining and land challenges sung about by Yothu Yindi from far north-east Arnhem Land or more recently Midnight Oil’s collaborative effort with aboriginal artists. For those who have worked with aboriginal communities, we understand that makarraṯa is about peace keeping and coming to a fair and reasonable outcome which is agreed by the parties involved. In Yolŋu culture, makarraṯa occurs over a long period. They understand that conflict causes pain, tension and anguish for everyone involved and results in the breakdowns of relationships that are valuable and should not be lost. Yolŋu value the time to cool down and regain their heads and hearts before continuing conversations that may perpetuate traumas and do further harm before people are ready.

If we think for a minute about our professional settings, relationships are attached and bound by appointment schedules, timetables, processes and meetings. Many human facing professions work under incredible pressure and are under resourced. Most workers in these areas are also generally very committed to the profession or service they undertake and the people they are working with. It is not surprising that in the pressure cooker of these contexts, colleagues fall out, clients and consumers get angry, families feel disenfranchised and the lack of time available to sit in the discomfort of those negative feelings and to work through or resolve them when the time is right for the individual leads to compounding conflict and increasing traumas in practises and workplaces. In the hectic life that we exist, most people struggle to embody a sense of peace nor have the head space for more complex negotiations towards a notion of treaty or reconciliation with self, little own known and unknown others.

It is then little surprise that the HEART becomes worn. Wearing the stories, experiences and traumas of people we work with is exhausting and less resources frequently equate to less supervision or debriefing. Conflict with our colleagues is debilitating. Our ability to feel for another or to care for ourselves also becomes compromised. In professional speak, this is commonly referred to as compassion fatigue and though we can easily take an inventory questionnaire to diagnose, the ability of professionals to continue working and resolve the ongoing demands on their affective selves begins to deteriorate. Personal lives exhibit the toll of emotional exhaustion and frequently the fallout is felt by families, friends and absences in places where there was once the energy and drive to exist. At that point, it seems easier to not to feel which also comes at a cost.

Though we know we need to hear the VOICES of others in our practice, it can get too hard and we find the shortest route to a best outcome. Hearing what is said and more importantly, making and attaching meaning takes significant cognitive and affective investment. Using one’s voice smartly and purposefully to convey meaning and make contributions to the lives of others takes effort and scholarship. Increasingly in the information age it is more important to be discerning and critical in consumption of text and media, to not get lost in a large crevice of noise.

To sincerely and deeply engage in processes of sorrow and reconciliation, we need to have time and health to feel the emotions, attach them to a known experience and then feel some contrition or that something is worthy of creating peace. We need to understand all sides of an issue or challenge and be brave and humble enough to interrogate it, acknowledging with vulnerability that we may be wrong. Most of all, we need to go gently with ourselves and with others. Life is hard and actions taken without reciprocal engagement of others are just further actions put upon them, even though we may be ready. We must value and commit to self-care in all aspects of our life in order to put our best selves forward to others – especially our First Nations peoples who have already had so many violent encounters.

Some commitments to make for preparing the self for activities connected to sorrow and reconciliation:

- Sit quietly with someone you have had conflict. Don’t try and fix it. Talk about what happened and how you might reach a peaceful resolution. Go away and then commit to coming back together after some time to revisit that idea.

- Become familiar with what peace looks, feels, smells, tastes, sounds like to you. Achieve peace for at least 15 minutes every day.

- Watch the story of Dhakiyarr, currently featuring on ABC I-View to understand the story of makarraṯa.

- Read Thomas Mayor’s fabulous book “Finding Our Heart. A story about the Uluru Statement for young Australians”.

- Own your feelings and explore how they change. Give yourself permission and time frames to explore the sad emotions. Identify strategies that lift you from a funk and re-energise and re-focus you.

- Remember that nothing good ever comes from guilt. It is not a productive emotion.

- When you feel tired, rest.

- Only carry your own stuff.

- Make intentions to treat others with kindness and courtesy and to save your love and affection for those closest in your personal life.

- Demand great supervision and debriefing in your workplace.

- Create rituals to begin work and end it. Don’t take the stuff from home to work or work to home.

- When it gets too hard, ask for help. Have a person on each finger you can reach out to.

- Add twenty other things you could do to look after yourself better.

SWIRLS Member, Professor Debra Bateman

DipT(Prim)BEdMEd(Thesis)(ACU)GCHE(Deakin)PhD(ACU)

Adjunct to Rural and Remote Health

College of Medicine and Public Health

Flinders University

Principal and Community Advocate/Liaison – Mäpuru Yirralka College

self-determined lives of dignity on ancestral estates

To learn more about Mäpuru visit: https://www.aisnt.asn.au/schools/mapuru-christian-school and www.arnhemweavers.com.au

![]()