A Pragmatic Strategy to Contain the Spread of COVID-19

Executive Summary

We know that COVID-19 has a reasonably long incubation period, approaching a week and possibly longer in some individuals. We know that COVID-19 is infectious in the early, asymptomatic stages of the disease when infected individuals are unaware that they have the disease.

It is argued that substantial differences in the rate of spread in different countries is due to differences in the relative densities of infectious, but asymptomatic individuals. Where Japan and Italy had similar numbers of COVID-19 positive tests (approximately 140) on 23rdFebruary, now on 15th March Italy has 24 times the number in Japan, and this difference is growing. It is shown that some 90% of those who have the disease in Italy are asymptomatic and (presumably) still active within their communities. That figure is approximately 40% in Japan which accounts for the difference in numbers of new infections.

On this basis, a strategy to reset the number of active infected people in any country or community back to low and manageable numbers is proposed. The approach involves self-isolation (for 1-week) of everyone other than essential service providers. This allows a large proportion of infected but asymptomatic people to become aware of their infection without infecting others. At the end of the week the infected population naturally sorts into ‘ill’ and ‘not ill’. Those who are ‘not ill’ can resume normal activity, in the knowledge that the ‘ill’ are largely not among them. Provided testing continues, another reset can be organised when the numbers of infected individuals grows to the point that a) hospitals are approaching capacity limits (ventilators, ICU beds etc) and b) ‘normal’ life within the community is becoming disrupted by fear.

The proposal concludes with a short discussion on social and economic considerations. It is argued that the predictability of a single week shut-down in a cycle of some (4 or more) weeks is less damaging to a nation’s economy and the livelihoods of its workers, than the unpredictable effects of the viral avalanche that currently threatens. In addition to the lives saved, there are great gains in resilience of the social fabric and trust in governance. The cycle of periodic shut-down should continue until either a) the virus naturally fades perhaps due to seasonal effects, or b) a vaccine becomes available.

Intro

- In the past week or so, the weight of official and broadcast narratives (e.g., WHO and national leaders) on coronavirus has switched from preventing the disease taking hold, to diminishing its impact as it runs its course across each nation.

- Why has the case for containing the outbreak seemingly been pushed aside, especially as it seems that China, and perhaps Japan and the Republic of Korea, are making headway slowing and possibly halting its advance?

- Shutting down a nation and enforcing mandatory isolation are somewhat draconian measures to be sure, and they carry the dual harm of shutting down economic activity and people’s livelihoods.

- However, the question we ask is whether there is a rational proactive containment strategy, a largely voluntary middle ground so to speak, that both slows the spread of the virus and accepts a moderate but predictable level of economic damage.

- In the absence of a containment strategy it appears inevitable that many countries will experience an unchecked viral avalanche, with attendant harms to national health and health systems, as well as potentially irreversible damage to economic foundations, and social and political resilience. Are there rational, sensible and affordable alternatives?

- We argue here that such an alternative is available. There is no such thing as a free lunch and there are costs to all of us. But it’s important that we understand the ‘left and right of arc’ or what’s achievable through design and active management rather than, as the flavour of current rhetoric would suggest, there is no choice, but ‘we will come through it in the end’.

- To understand options, we first need to look at the way COVID-19 has behaved thus far.

- Many have seen the ‘dashboards’ that display the numbers and graphs of covid-19 positive tests as they have grown from mid January, initially within Hubei Province in China, then across China, and now across the globe (https://who.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/c88e37cfc43b4ed3baf977d77e4a0667).

- The data have some inconsistencies but the message is clear. Coronavirus spread, like that of many other viruses, is exponential, that is, its growth accelerates.

- With just the briefest wink at mathematics, exponential growth means that the number of cases doubles in a fixed amount of time. For the sake of illustration, let’s say that it doubles every 5 days, which is what was seen in COVID-19’s early days in China. Let’s say we start with 1,000 cases. One day later there will be (about) 1,149 cases (day-1). Another day later there will be 1,320 cases (day-2). On day-3 there will be 1,516 cases. On day-4, 1,742 cases, and on day-5, 2,000 cases, i.e., double what we started with.

- The reason for growth is that infected people infect others. Epidemiologists talk about a reproduction number, or the number of other people that any one infectious person typically infects. The reproduction number is related to viral infectiousness and is a measurable, but unpredictable characteristic of each virus. Coronavirus seems to have a reproduction number between 2 and 3 – for every person who has it, between 2 and 3 other people will get it – which is why it grows so rapidly. If the reproduction number were less than 1 then the ‘epidemic’ would fade out.

- Some parameters characterise the virus itself, such as its incubation period [1], its infectiousness, and its virulence [2], while other parameters, like reproduction number or case mortality [3], describe its macroscopic behaviour in real communities.

- The doubling period is one such macroscopic parameter. In its early days before the Chinese imposed local and then broader lock-down, COVID-19 cases appeared to double every 5 days. By reducing healthy people’s exposures to infected people the doubling time was increased and now currently stands at several weeks. This means the growth has largely been halted, through policies and social behaviours.

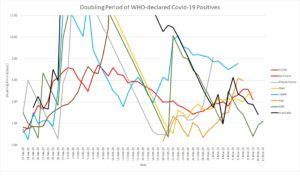

- Check the graphic below and you will see how the doubling time has changed in each of several countries, from 23rd January to 11th March 2020.

- In some countries, and in the early days after the virus first appeared in each country, the numbers remained static for several days. This is why the traces rapidly rose to large values (until late February for most). As the number of cases grew the doubling period became less erratic, and different nations settled toward different values. The red trace, for example, represents all infections outside China, as an aggregate of different country’s management and social behaviours.

- In fact China has largely halted the spread of coronavirus (at least in reported figures) and the China trace (brown) rises off the chart by 10 February 2020, and does not return. It means that whatever the number of cases was on 10th Feb, that number has not doubled yet [4].

- Japan and Italy provide an interesting contrast. Japan has, through its management of citizens’ exposure and social behaviours, achieved a doubling time above 4 days, and more recently something closer to 8 days. Italy, however, initially saw a doubling time close to 2 days which has recently risen to 4 days.

- On 23rd February the COVID-19 positive case numbers in Japan (144) and Italy (132) were essentially the same. On 15th March (3 weeks later), Italy was reporting 17,660 cases compared with Japan’s 716, a factor of 24 difference.

- This is like the old fable about doubling the rice grains on successive squares of a chessboard – there aren’t enough rice grains in the world. When Italy’s doubling time was 2 days and Japan’s was 6 days, Italy’s case numbers doubled 3 times for every one doubling in Japan. It means Italy had 4 times more cases than Japan after the first 6 days. The effect, as it accumulated over quite a short time, means that Italy now has nearly 24 times the number of infections as Japan.

- The graphic makes it clear that the various countries, through different policies and social behaviours, are achieving quite different outcomes [5]. China, the Republic of Korea and Japan have slowed the growth of COVID-19 infection greatly. Italy, Iran, the USA and Australia, by contrast, are suffering very rapid growth.

- To make this crystal clear, in the week to 15th March Japan was seeing about 30-50 [6] new cases each day, which is likely to be manageable within the capacity of its health systems. Italy, on the other hand, was seeing more than 2,000 cases a day, probably overwhelming health system capacity, and likely compromising outcomes for those with the virus, as well as all others in need of medical help.

- The difference in viral growth rates (doubling periods) relates to official policies and the behaviours of infected people, but to understand precisely why, we need to look a bit more closely at where transmission is occurring.

- The doubling period is not a fundamental characteristic of this or any other virus. It actually reflects gross community behaviours, but particularly the number of unidentified, infectious people within the community. Before we explain, we first need to understand one of the fundamental virus parameters, namely incubation period.

- It has been reported that some people have contracted COVID-19 but have not become symptomatic for up to 20 days. This is the incubation period, when people are infected but before they become symptomatic. More recent reports indicate that the incubation period for COVID-19 is, most commonly (median?), between 5 and 6 days, although some cases, as noted, have been substantially longer.

- It has also been reported, for COVID-19, that infected people shed virus (they are infectious) in the early, asymptomatic (non-symptomatic) stages of the disease. Viral shedding declines as they approach and enter the symptomatic stages.

- Even though a significant number of people experience fairly mild symptoms when they do appear, the appearance of symptoms makes them more likely to self-isolate reducing the probability of infecting others. This means that the spread of COVID-19 is primarily due to the presence of viral shedding, infected but asymptomatic people remaining active in the community, because they do not know they are infected. How many of these people are there?

- We can calculate their number if we know both the incubation and doubling periods. Let’s say that the incubation period is 6 days and the doubling period is 3 days. Hypothetically, today is day-zero and at noon today let’s say that 100 people are known to be COVID-19 symptomatic. With a doubling period of 3 days, then 3 days later (on day-3) there will be twice as many, or 200 symptomatic people (100 of whom contracted the disease 6 days earlier on or around day-minus 3). On day-6 there will be 400 symptomatic people, i.e., doubled again, and 200 of those contracted the disease 6 days earlier, on or around day-zero.

- If we add up all the people who contracted the disease on or before day-zero it comes to 400, i.e., 100 who were symptomatic, and 300 who were asymptomatic on day-zero (who became symptomatic by day-6). In other words, the combination of a 6-day incubation and a 3-day doubling period means that 75% (300/400) of the infected people did not know they had the disease. If they remained active in the community, this is where the new infections came from. We can see that the doubling period is actually a reflection of the number of asymptomatic people who remain active in the community.

- Typical numbers are as follows, assuming that the incubation period (from evidence) is 6 days:

- In Italy, where the doubling period was 2 days, some 87% of infected people were asymptomatic

- In Japan, where the doubling period is now close to 8 days, some 40% of the infected are asymptomatic

- If the actual number of known-symptomatic cases were the same (as they were on 23rd February) then Italy would have more than twice as many ‘hidden’ or unknown and unknowing infectious people as Japan, by virtue of their different doubling periods. Clearly Italy has the much more difficult situation to manage.

- The aware-infected are just the tip of the infection ‘iceberg’.

Resetting the clock on the growth of infections

- If we accept that the growth of new infections is primarily caused by the movement of asymptomatic but COVID-19 positive people within the community, we need a way to identify who these people are, and then isolate them so that they cannot cause further infections.

- There is no ‘remote’ sensing technique to achieve this goal, at present.

- So, the approach we advocate (as demonstrated in Asian countries) is to self-isolate as many people as possible. For how long? For a time that’s similar to the incubation period: around 6 days.

- While there is a small number of asymptomatic individuals who incubate the disease for longer than 6 days, the majority of hidden carriers will know that they are infected after, say 7 days, or 1 week.

- By removing all but those persons who are necessary for the operation of infrastructure and essential services [7], and asking all others to voluntarily self-isolate, after 1 week most of those who are infected will know who they are. Many will stay at home until they recover, and some will need healthcare intervention.

- When everyone emerges after one week, apart from

- the small number of infected people who remained active in order to run primary services, and

- the small number of infected individuals whose incubation is unusually long, the vast majority of people will be infection-free, i.e., we have removed the hidden-infected from the community and we have essentially reset the clock on the viral spread.

- At this point normal activity can be resumed, and the numbers of infections (starting from a relatively small base) can be monitored, until such time as those numbers call for another reset period of self-isolation.

- A repeat cycle of 1-week voluntary [8] self-isolation, followed by 3, 4 perhaps 6 weeks of business as normal. The cycle is repeated until either

- the virus naturally fades, as it might in warmer weather, or

- a vaccine becomes available.

- It is also important to note that the numbers of infected in Australia are still quite small and manageable and this strategy, if implemented early, will be less damaging to economics and society. The first self-isolation period must ‘expose’ as many of the ‘hidden infectious’ as possible. If current numbers are allowed to grow, the initial period may need to be longer than a week to ensure that the people returning to the community are as virus-free as possible, so that they ‘dilute’ the infections that continued to spread in those people who remained working to provide our essential services.

- It is also noteworthy that the cycle ratio (1 week off: x weeks on) will differ according to the numbers of people who are deemed to be ‘essential’ and keep working. If that number is large, then the number of weeks of normal activity before a reset will be small. If many services are cut to the bones, then the period of normal activity can be significantly longer.

Economic Considerations

- While it is certainly advisable to conduct economic modelling to clarify specifics and assist planning and communication, the principles involved in this strategy should be plainly evident.

- Without such intervention, as we have seen in Hubei Province China and in Italy, relatively ‘heavy’ social management policies and enforced controls may be required. Such controls have been imposed without communication of when they might be lifted. Allowing unfettered viral spread has the potential to cause many different forms of damage to a nation and its social structures. Health systems will certainly be overwhelmed and many people will die who would otherwise be treated if the system were less overloaded. The unforeshadowed lockdown of businesses without a communicated end date will cause considerable economic damage and many businesses will fail where (perhaps) a known end date may keep the creditors at bay. When not in lockdown, fear can cause unpredictable social responses, such as the irrational stockpiling of toilet paper seen in Australia (which occasionally sparked violence) – this was relatively benign but could cause considerable hardship if other commodities were involved – distrust of fellow citizens and distrust of government. Fear of meeting infected persons will cause people not to visit business premises when they are operating (cafes, restaurants, hairdressers, movie theatres, shops, libraries etc) and any form of mass gathering (schools, universities, sports, clubs etc) will see little or no activity. At least one parent of young children will be forced to stay home for childcare and fear of going to work could disable many essential and important services, for example, in the distribution of food and other logistics. Defence may provide a partial but limited fallback in both numbers and durations.

- This is the future we are currently exposed to on the news, and one that we are being prepared for by commentators and spokespeople. But it is unnecessary.

- Adopting a planned and scheduled cycle of 1 week off (perhaps) 4 weeks on for all but essential services, together with a campaign of communication about personal/community responsibilities, handwashing etc., has the potential to keep infection numbers low enough in the community to largely eliminate fear. The health system will perhaps be stretched, but this is one of the criteria that should be weighed in modelling to understand the cycle timing ratios (how long it is possible to operate business as normal before another reset isolation period).

- While no one would voluntarily close their business for a significant fraction of the year, the fact that the entire country is in predictable, voluntary self-isolation for a set period, means that losses are calculable and negotiable with creditors. It also means that compensation or economic stimulus packages can be budgeted in advance. This becomes a method for managing the economic and other forms of harm until such time as they are no longer necessary.

- Left to spread through the community, the economic harm is difficult to estimate (how many businesses will fail?), and even though current rhetoric focuses on the upturn ‘on the other side’, such an upturn may take place within a society which has been traumatised by the deaths of many family members and workmates, tearing the social fabric of the nation.

- As well as economic and social harm minimisation, other key benefits of a structured approach to containment are predictability, which enables planning and effective communication, and strengthened trust in government.

- We have the opportunity to keep the country running, albeit at a fractionally slowed pace, and accept limited but calculable harm. A containment strategy means that we no longer need to close borders because COVID-19 monitoring allows us to understand growth and adjust when the next reset period should occur. A country that has effective infection management and is largely infection-free (since the objective is to reduce numbers so that fear is largely eliminated) becomes a very attractive travel destination, which may partially compensate for expected economic losses.

Professor Rick Nunes-Vaz & Professor Paul Arbon, Torrens Resilience Institute, 15th March 2020.

[1] how long between contracting the disease and becoming symptomatic

[2] how severe an infection it causes

[3] approximately how many people of a certain age, health status etc. it kills

[4] This is slightly more complicated because of the numbers of recovered people, but the principles hold

[5] provided testing continues and case numbers are valid

[6] ibid

[7] arrangements to strengthen food delivery capabilities and capacities are important to prevent panic buying and assure that supply chains keep functioning.

[8] This requires an education campaign through media, giving each individual part responsibility for the community’s continuing health, i.e., not causing unnecessary pain to vulnerable members

“Where Japan and Italy had similar numbers of COVID-19 positive tests (approximately 140) on 23rd February, now on 15th March Italy has 24 times the number in Japan, and this difference is growing. It is shown that some 90% of those who have the disease in Italy are asymptomatic and (presumably) still active within their communities. That figure is approximately 40% in Japan…”. It means that there are 9 times the number of known infections in Italy (i.e., over 150,000 people) who are unaware that they are infected, and are presumably still active in the community. This compares with 2.5 times the number of known infections in Japan (i.e., about 1,800 people). That’s over 80 times more unaware-infected people walking around in Italy than in Japan, which explains the massive difference in their rates of spread.