One of the most important parts of reading at university is figuring out how to read well. And it’s not as easy as it seems. We read in different ways depending on our purposes. Sometimes we need to read closely and in depth, sometimes we may only need to skim and scan, and sometimes we may not need to read a text at all. It all depends on what we need to gain from our reading, or what our expectations are. So, we’re going to look at two strategies for effective reading. The first is my simple five step process, and the second is a strategy called SQ3R.

Five Steps for Effective Reading

1. Purpose

The first and most important step to reading effectively is to understand your purpose for reading. If you know why you’re reading, you’ll have a much clearer idea of what content you will need to pay attention to.

So, begin by asking yourself some questions:

- What do you think your lecturer wants you to understand?

- How does the article fit with the topic concepts?

- Are you reading to develop an overview or general understanding of a concept?

- Do you need to discover a particular argument for an assignment?

- How familiar are you with the text or its content?

- Do you need to do some background reading?

- What are some key words and phrases to look out for?

Your purpose will determine how slowly or quickly you will need to read, how much you will need to highlight, annotate or note, how much of the text you can skim and scan, and what you may need to re-read and come back to.

Plus, thinking about why you’re reading, especially a question like how the article fits with topic concepts, can really help you understand a text. This is because you’ll be better able to frame and contextualise the information you’re reading. It can sometimes be difficult to wade through all of the complex language of a text and differentiate background information from the article’s real aim or central argument. Defining some things for yourself first can help you narrow in on what’s most important.

2. Predict

The next step is to predict what you think you will find in the text. This means thinking about what you already know about the topic. What concepts have been covered in lectures, tutorials or other readings? What do you already know about this concept from past topics, your general knowledge or your own experiences? What have you heard other people say about the subject?

This can help you figure out your expectations for the text. We all have experiences and knowledge that we’ve collected through our lives, and this means there are many associations we can make between ideas in our minds. Even if you aren’t particularly familiar with the topic, you may have other similar knowledge that can help you to frame and contextualise it.

If you have almost no previous knowledge or context to help you frame the article, you may consider doing a bit of background reading. This means picking up a topic specific dictionary or primer, or even doing a quick google of the subject. Remember though, while Wikipedia and similar sites can help you at this early stage of understanding, they should only ever be a starting point!

3. Skimming and Scanning

If you have spent some time thinking about why you’re reading and what you expect from the text, then you’ll be able to effectively skim and scan to find what you need. We skim and scan the text when we know we don’t need to read the entire article in depth, or if we’re unsure if the text is useful to us and we want to gain a quick overall picture of what it is about. This can also be a useful way to prep yourself for a difficult text, by giving you an overall idea of what content it will cover so you can do some pre-reading or look up any difficult words or concepts.

Skimming

Skimming is when we move our eyes quickly over the entire text to gain a general idea of the content. Think about how you might read a newspaper (if you still do such a thing!) You don’t necessarily read every single word, or the whole paper from beginning to end. You might read the headlines and your eyes will glance over the text and find words that jump out at them. So, by the end, even though you haven’t read the newspaper from cover to cover, you’ll have an idea of what major stories it covered, even if you didn’t read the articles. You’ll also know which articles you want to come back to and read in detail.

You can do the same thing with reading, particularly when researching for assignments. Say you’re looking for a particular theory for an essay. You might begin by downloaded five or six articles with relevant titles. Start at the beginning of one of the articles and let your eyes glide quickly over the words. You don’t need to take in every single word or detail: you’re familiarising yourself with the material and looking to see if and where the authors discuss the theory. If they do, you might go back and read the article in depth. Or, if they discuss the relevant theory but only in a certain section, read that section properly. If they don’t discuss the theory, then you know not to waste your time reading that article.

Some techniques for good skimming include:

- Read the abstract so you get an overall picture of the article first

- Think about what the author’s aim or argument is to help you sort important material from the background

- Pay closer attention to the topic sentences of each paragraph than the body

- Read vertically as well as horizontally

Scanning

Scanning is when we look out for particular and specific words or items of interest. It’s a bit like scanning a crowd to find your friend – you’re not necessarily paying attention to every single individual, you’re looking for what’s familiar to you. This is where preparation is really important. Use lecture notes, essay questions and class discussions to help you identify keywords and concepts.

You might be looking for a particular name, a fact or figure, a quote, or a theory. Let your eyes move quickly over each sentence, and pay attention to headings, subheadings and topic sentences, and stop when you find an important word or phrase. Then, slow down and read that section properly. Then you can determine if you need to read the whole article, just that section, or if you can skip it. If you’re reading a book, using an index can be super useful too.

Some techniques to help you scan include:

- Scan the contents page for any key content words that leap out at you

- Have a look at the index to see if particular topics are covered

- Use graphics such as graphs and tables and read their captions for context clues

- Look out for words in bold or italics

- Read each heading and subheading

Both skimming and scanning are preparatory techniques and don’t replace close analytical reading. They help us locate what we need and put aside what we don’t. The next step is to read carefully.

4. Read Closely

Once you’ve decided what you need, it’s time to read closely and become critical and analytical. This means we need to really slow down and read in detail. Close reading a text is all about asking questions, thinking carefully and trying to fully comprehend what the author is saying. Reading closely may require you to read more than once – in fact, reading twice, or even three times, is recommended!

Read the text the first time to gain a general understanding. Underline or highlight anything you don’t understand and need to look up in the dictionary. Try not to interrupt the flow of your reading too much though. At this stage, you want to be able to figure out what the author’s main points are, and what areas you are unfamiliar with or are having difficulty with.

In the second read through, pay close attention to the main ideas of the article: what is the research question? How does the argument progress through each paragraph? You will want to pay particularly close attention to topic sentences and headings. This can give you a good insight into the key purpose of each paragraph, and how each idea connects together. If you find yourself lost in a text, always come back to the first sentence. Sometimes, I find it useful to write myself a very brief note in the margin next to each paragraph explaining what the main point was. This allows me to keep on track and ensure that I’m not getting confused or bogged down by the details. This can be especially tricky as often authors will provide lots of examples, detailed background, or refer to a lot of other literature. It’s important to try to distinguish between the author’s own points, and the ideas, examples and evidence that they are bringing in to support those points.

It’s also useful to look out for key discourse markers (I gave a run-down of some of these and what they tell us about the article’s structure in my previous post!). These will tell you when the argument is shifting, when the author is introducing a key author, when they are describing process or method, or when they are offering a contradictory point. It’s important to pay attention to tone as well, such as asking if you think the author agrees or disagrees when they refer to another author?

So, some things to pay attention to include:

- What is the overall aim or argument?

- What are the key points that support that argument?

- How does the author connect their key points to the argument?

- OR, can you identify the methods, results, discussion and implications?

- What evidence or examples does the author use to support their points?

- How do they relate these examples to the question?

- What devices do they use? (Eg, definition, explanation, evaluation, description)

Reading closely is also about evaluating and analysing a text. I have an entire post about techniques for that coming soon!

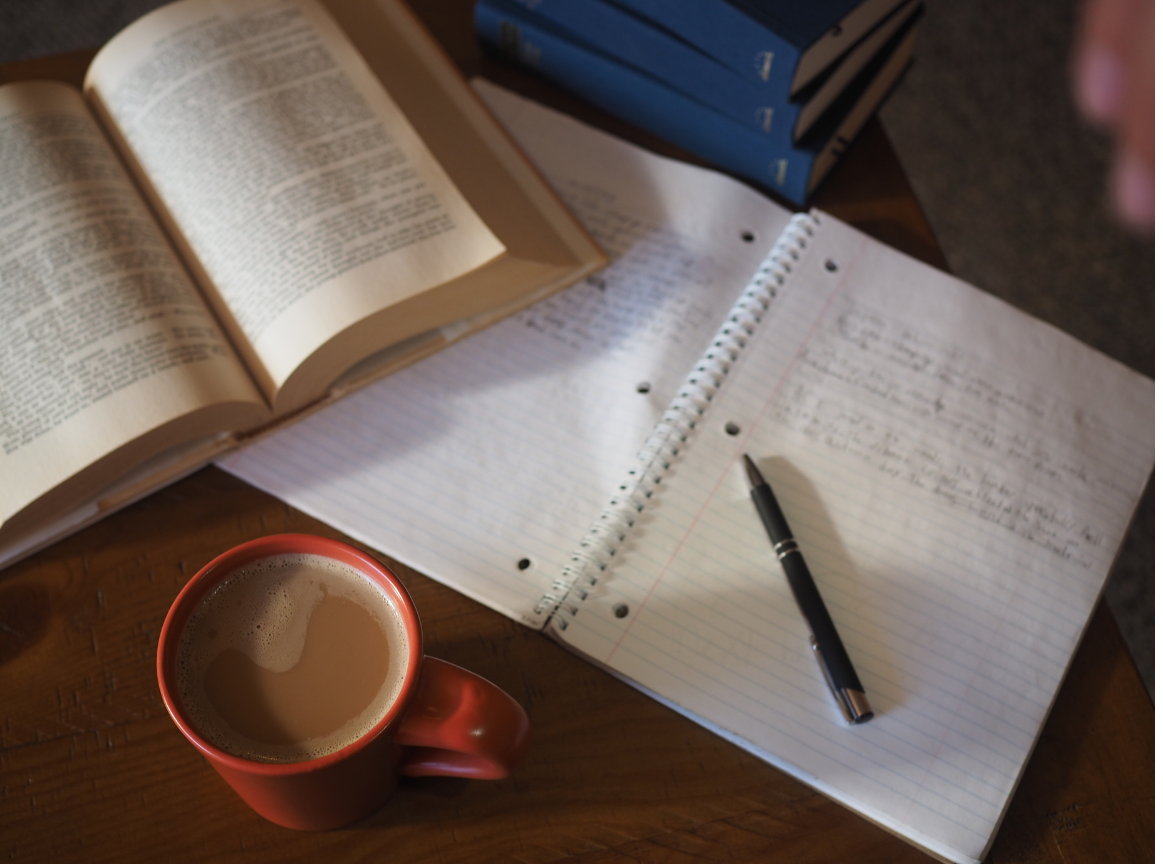

5. Take Notes

The best way to ensure that you not only remember what you’ve read, but that you understand it, is to take notes. The ability to turn information into your own words demonstrates that you comprehend concepts. Plus, this process of transcribing information will significantly increase your chances of remembering it, and develop your critical thinking skills.

But knowing what to make notes of, what to highlight, and what to leave can be very tricky. I’m super guilty of making far too many notes because I’m afraid I’ll miss something important. This can be a time-consuming process, so – again – it’s important to make sure we prepare!

Start by asking yourself why you need to take notes. Is it to understand information? To memorise for a test or exam? Or as research for an assignment?

Taking notes to understand:

- Write questions for yourself in the margins of the text

- Highlight or underline words or concepts you need to look up

- Include definitions or reference points in your notes

- Try to paraphrase as much as possible. If you can’t paraphrase, you may need to do some extra reading to help you understand the concept

- Use diagrams and graphic images to help you connect ideas together

- Make links between the reading and topic material, such as lecture content

Taking notes to memorise:

- Note only the most important information, leaving out unnecessary details and examples

- Link your points to a familiar sequence (or a song, list or rhyme), so you when you recall the sequence, you can remember all the points

- Use diagrams, sketches and concept maps to aid your memorisation

- Colour code information, or organise it according to visually distinct themes

- Write your notes on flashcards that you can use during revision

- Cover over the original before you write then check back for accuracy

- Make up your own examples to help you understand and remember

- Re-write your notes to cement them in your memory

Taking notes for research:

- Start with an overview article or book to help you understand the key points

- Create headings with key concepts or themes you need to address in your assignment.

- Only note what is relevant to the assignment question or your argument

- Record bibliographic details (at least the author and page!)

- Use abbreviations and keep notes brief. This will help you paraphrase later on

- Be clear about when you are paraphrasing and when you’ve copied word for word

It’s important to make sure you use a new notepad or Word document that is clearly labelled, and set up some kind of organisational system.

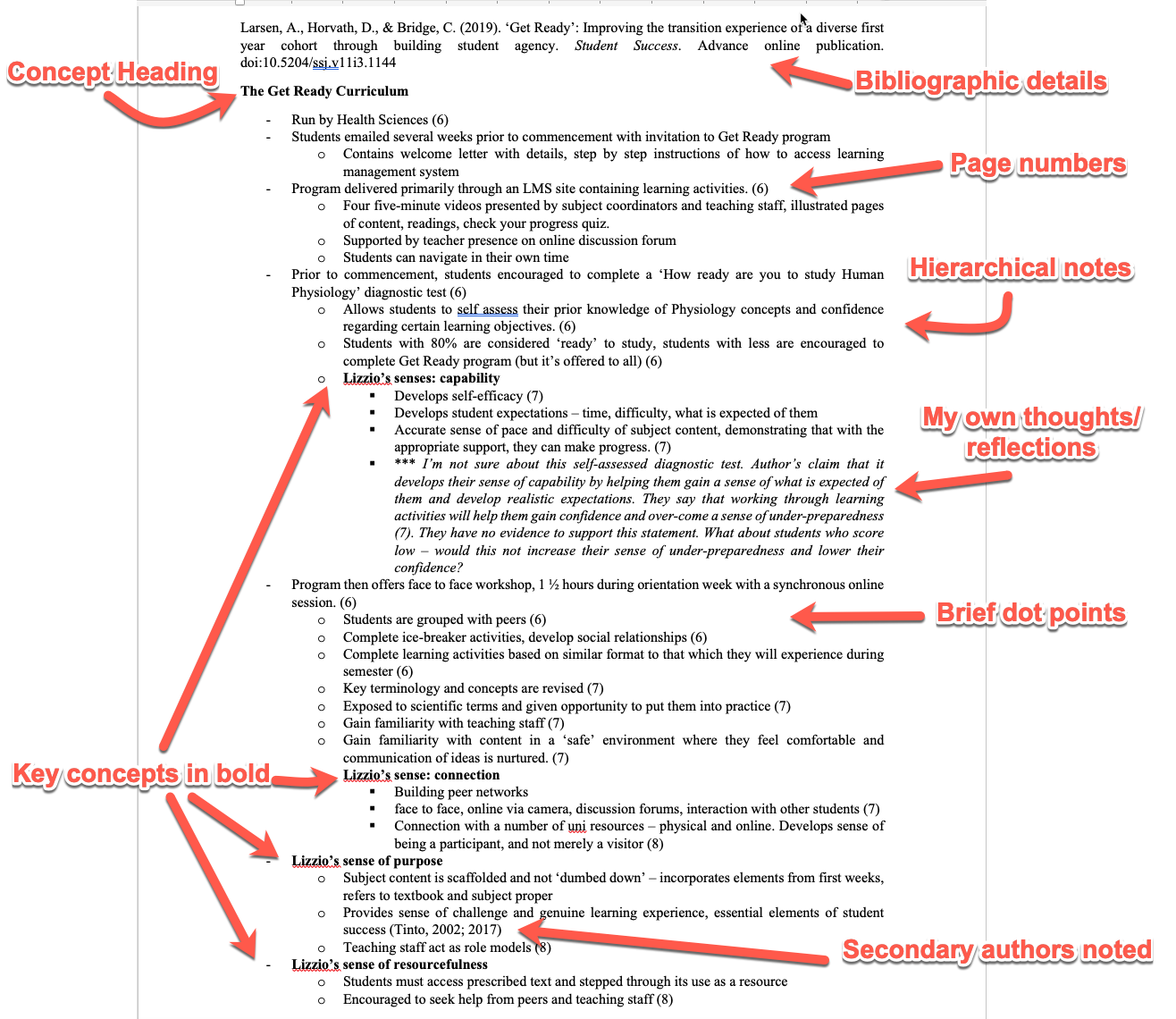

Personally, I always use headings to organise notes according to key ideas, concepts or themes. I include the bibliographic details at the top (you never want to forget where you got something from!) and pop the page number of the article next to every dot point that I write. I use a hierarchical method of note-taking so that I can see links between ideas, and I try to keep my notes as brief as possible so that I’m paraphrasing and capturing only the most important ideas. If I have ideas about what I’ve read, including what I may agree or disagree with, or links I can make to other ideas, I include them and clearly seperate them from the rest of my notes to avoid confusion.

Also, try to be very sparing with your highlighting. If you highlight too much, you may as well highlight nothing at all! I only ever highlight the article when I want to be able to find an important idea again. This way, highlighting becomes a useful reference tool for myself, rather than an information processing tool.

Here’s an example of my note-taking:

SQ3R Method

One particular method that is recommended by academics is called the SQ3R reading method. It uses very similar techniques as I’ve described above.

Survey: Scan the material you want to learn to get a picture of the overall argument or the are covered by the book or article you are reading

Question: Ask questions of the text. Turn any headings or subheadings into questions, and then try to answer them in your own words.

Read: Go through the text in the light of the questions you have asked, and take notes at your own pace and in your own words.

Recall: Close the book and try to remember what you have read. Try to write down what you remember in your own words. Only by testing your recall will you know how successful your learning has been.

Review: Later, go back over all your notes to make sure you don’t forget to see how what you have learned relates to the course as a whole, your other reading and what you still need to do.

References

Hay, I., Bochner, D., Blacket, G., & Dungey, C. (2012). Making the grade: A guide to successful communication and study. Oxford University Press.

Weinstein, Y., Sumeracki, M., & Caviglioli, O. (2018). Understanding how we learn: A visual guide. Routledge.