Dr Deidre Morgan, Senior Lecturer, Palliative and Supportive Services, Research Centre for Palliative Care, Death and Dying, College of Nursing and Health Sciences, Flinders University

While often inductive and iterative by nature, strong qualitative research methods are underpinned and guided by a defined worldview which requires a conscious consideration of ontology (our way of being in the world, the nature of reality) and epistemology (the study of knowledge and how we examine this way of being or reality). (1)

Qualitative research plays an integral role in helping us understand the issues that face people at the end of life, from all perspectives. However, as the palliative care and end-of-life evidence base grows, so too does the number of studies reporting qualitative findings that do not articulate any ontological and epistemological foundations. This in turn affects the degree to which it can be critically interpreted and practically applied.

This blog examines one aspect of qualitative research, thematic analysis, a popular method for analysing qualitative data in studies investigating end-of-life issues and how we might strengthen our methodological approach.

What it is: Thematic analysis is applied to data from focus groups and semi-structured interviews through to free text responses collected in surveys or online through web pages. However, the quality of the thematic analysis can vary greatly.

Braun and Clark wrote a foundational and highly cited paper that outlined a structured approach to the use of thematic analysis in qualitative research. (2) What made this paper attractive was the authors’ flexible application of thematic analysis to a range of research disciplines, philosophies and its applicability to a broad range of research questions. However, in a recently published paper (3), Braun and Clark emphasise that their thinking has evolved since the initial discussion of the topic 14 years ago. They have refined their approach, now called reflexive thematic analysis. They also note with concern, the indiscriminate and inappropriate application of their thematic analysis methods to health research. Braun and Clark propose that application of reflexive thematic analysis must be consistent with theoretical foundations underpinning a study, and not simply applied post hoc (i.e. as an afterthought when looking for a reference to ‘bung in’ the methods section after the analysis is completed). They have established a website for researchers who are interested in the rigorous use of reflexive thematic analysis. The University of Auckland website contains practical information and FAQs about the application of this method, including considerations for coding, theme development and theoretical foundations. It also provides an informative checklist for researchers and reviewers to ensure research questions and methods align with reflexive thematic analysis methods. (4)

How to apply it: So how do you manage analysis of qualitative text that does not align strongly with a theoretical framework – for example, analysis of free text survey responses? Patton proposes that content thematic analysis may be a useful and pragmatic approach here, whereby free text is analysed by searching for recurring patterns (sometimes counted as frequencies) and themes in the data. (5) He suggests a pattern is a more granular description of a finding (e.g. there was a pattern amongst participants of feeling anxious about hearing bad news). A theme, on the other hand, interprets the broader meaning of the pattern (e.g. management of anxiety at the end-of-life). Content analysis is differentiated from other thematic analysis by the potential to use frequency of categories as a proxy for significance. (6) It may be used inductively where themes are constructed from the data or deductively where theme development is driven by pre-existing knowledge or theory. (7)

However, Patton and others support Braun and Clark’s contention that the analysis process should not occur within an atheoretical vacuum. (8, 9) They propose that a pragmatic worldview and approach to research fits to health research. Pragmatic by name and nature, the flexibility and relevance to everyday life of a pragmatic worldview can provide an ontological and epistemological foundation in which researchers investigating what works in real life situations can situate their research. This is particularly relevant in an end-of-life context where pragmatic decisions that affect peoples’ lives are made every day by clinicians, patients and carers.

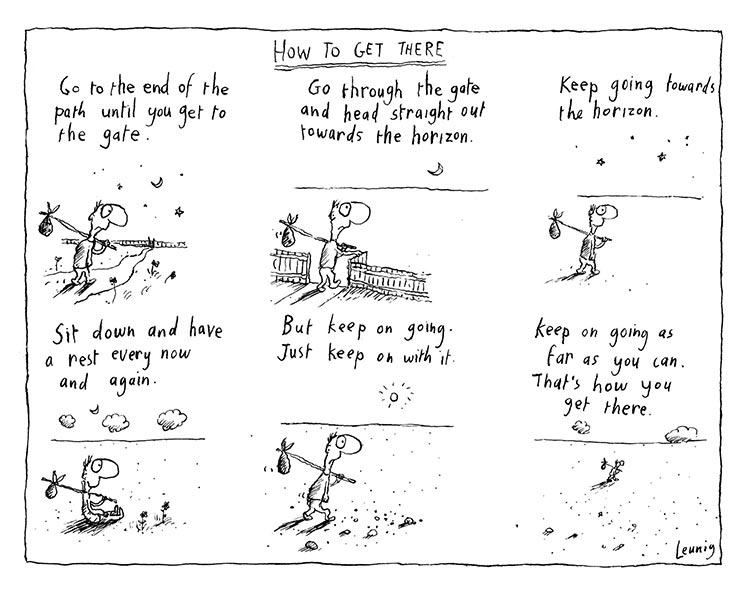

How to get there: Some take home messages as we meander back to ‘How to get there’. All researchers have a responsibility to be aware of the ontological and epistemological approaches that inform their research approach. They may be pragmatic in nature, phenomenological, or ethnographic to name a few. Importantly, all researchers need to be able to articulate what approach they are taking. The development of a clear well-defined research question at the outset of a study is critical and will guide all subsequent methods and analysis. As researchers in end of life and palliative care, we have to take responsibility for how we design our studies and collect data with vulnerable populations, but also in how we conduct our analysis. While analysis does not impose a burden on our participants, we have a duty of care to analyse it with the same rigour in which clinicians provide clinical care – with forethought and in line with best research practice wherever practicable. ‘How we get there’ is vital as our findings may inform future care and/or policy for those at the end of life.

References

1. Hathcoat JD, Meixner C, Nicholas MC. Ontology and Epistemology. In: Liamputtong P, editor. Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2019. p. 99-116.

2. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77-101.

3. Braun V, Clarke V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2020:1-25.

4. Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis | a reflexive approach: The University of Auckland, New Zealand; 2020 [Available from: https://www.psych.auckland.ac.nz/en/about/thematic-analysis.html]

5. Patton M. Qualitative analysis and interpretation. In: Patton MQ, editor. Qualitative reserach and evaluation methods. 4 ed: Sage Publications; 2015. p. 521-32.

6. Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15(3):398-405.

7. Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107-15.

8. Creswell J, Creswell J. The selection of a research approach. Research design Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches2018. p. 3-22.

9. Morgan DL. Research Design and Research Methods. Integrating Qualitative and Quantitative Methods: A Pragmatic Approach: Sage Publications, Inc; 2017. p. 1-16.