Written by Dr Seth Nicholls, Research Associate, Research Centre for Palliative Care, Death & Dying

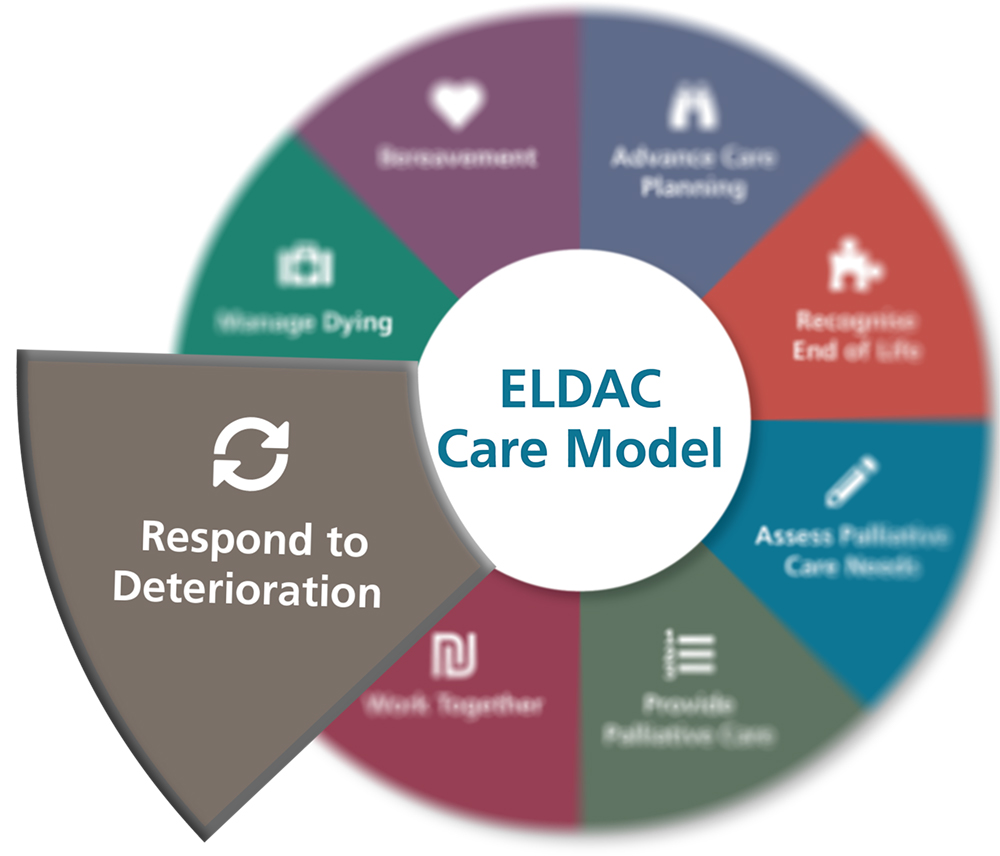

The End of Life Directions for Aged Care (ELDAC) Care Model provides health professionals and others working in the aged care sector with a framework that can be used to meet the needs of older people nearing the end of their life more effectively. Comprised of eight elements or domains a key aspect of the model is the need for health care professionals and others to respond to deterioration in a way that ensures changing patient needs are identified and met. To do so, individual care providers need the knowledge, skills and confidence to recognise deterioration; while organisations need to ensure that appropriate policies and procedures are in place to assist patients, clinicians and others.

Whether residing in a community, hospital or aged care setting, a timely and appropriate response to deterioration is often dependent on a patient and/or family members’ ability to recognise that deterioration is occurring and alert health care professionals. However, the ability to recognise – and therefore respond – to deterioration can be hampered by a wide variety of issues. These issues range from an inability to recognise and/or correctly interpret the meaning of symptoms to a patient’s reluctance to seek treatment. Moreover, deterioration itself can deprive patients of the cognitive ability needed to recognise and respond effectively.

Issues

In the course of an investigation into Older people’s decision-making and management of their chronic health conditions at home following discharge*, our research team identified a number of issues that had the potential to affect whether or not deterioration was recognised and action was subsequently taken. (1) For example, while many of the patients interviewed were confident they could recognise deterioration, descriptions of actual patient experiences with deterioration suggested otherwise; with many dependent on family members and others for recognition.

Moreover, a number of patients indicated that, in the event of deterioration, medical advice or assistance would not necessarily be sought. This inaction was attributed by patients to, among other things, ‘stubbornness’, a ‘she’ll be right’ type attitude and/or a general desire to not be a ‘burden’ on friends and family members. Determining the right course of action (once deterioration was recognised) was also identified as something that patients found difficult.

Dilemmas

Interestingly, our Study supported Rainey et al’s (2) finding that deterioration itself often deprives patients of the cognitive ability needed to recognise it. As one of our participants remarked:

“I don’t think I realised how sick I was, it was only the family that admitted me and talked to me about it later that I realised just how sick I was. I had four weeks in hospital then.”

This inability to recognise deterioration as a result of deterioration constitutes an insidious ‘Catch-22’ for health care professionals: How can patients be expected to alert family, friends, health care professionals and others to deterioration if the deterioration itself compromises their ability to do so?

Opportunities

Our research into discharge planning in Australia revealed that there are currently no national, mandatory requirements in place to ensure that clear, high quality information/instructions are consistently provided to patients. (3) Thus, a key recommendation emerging from our research is that a clear, printed plan of care be provided to patients before leaving hospital (as a means of reducing the likelihood of readmission). We also believe that such a document could act as a powerful vehicle through which to provide patients and family members with much-needed guidance in relation to deterioration; not only on ‘what to look for’, but, crucially, on precisely what action to take if/when deterioration is recognised. Taken together, these actions have the potential to prevent further deterioration by equipping both patients and family members with important and valuable information that renders appropriate and timely intervention far more likely.

References

1. King L, Harrington A, Nicholls S, Thornton K, Tanner E. Preventable readmission: older adults and family views on self-management of chronic health conditions at home after discharge. Article under consideration.

2. Rainey H, Ehrich K, Mackintosh N, Sandall J. The role of patients and their relatives in ‘speaking up’ about their own safety – a qualitative study of acute illness. Health Expect. 2015;18(3):392-405.

3. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. National guidelines for on-screen presentation of discharge summaries. Sydney 2017.

*The study involved in-depth interviews with older adults (and their family members) who resided in the community, had been discharged from hospital and managed one or more chronic conditions. Nineteen patients and eight family members were interviewed.