A study of more 10,000 students in China showed that low-performing students negatively affect their peers’ grades in Year 7.

The more struggling students in the grade, the worse the effect. But parents anxious about bad influences shouldn’t panic just yet.

There was no effect on high-performing students. And by Year 9 in the same group of students, the negative effect from peers had largely vanished, suggesting concerns may be misplaced in the longer term.

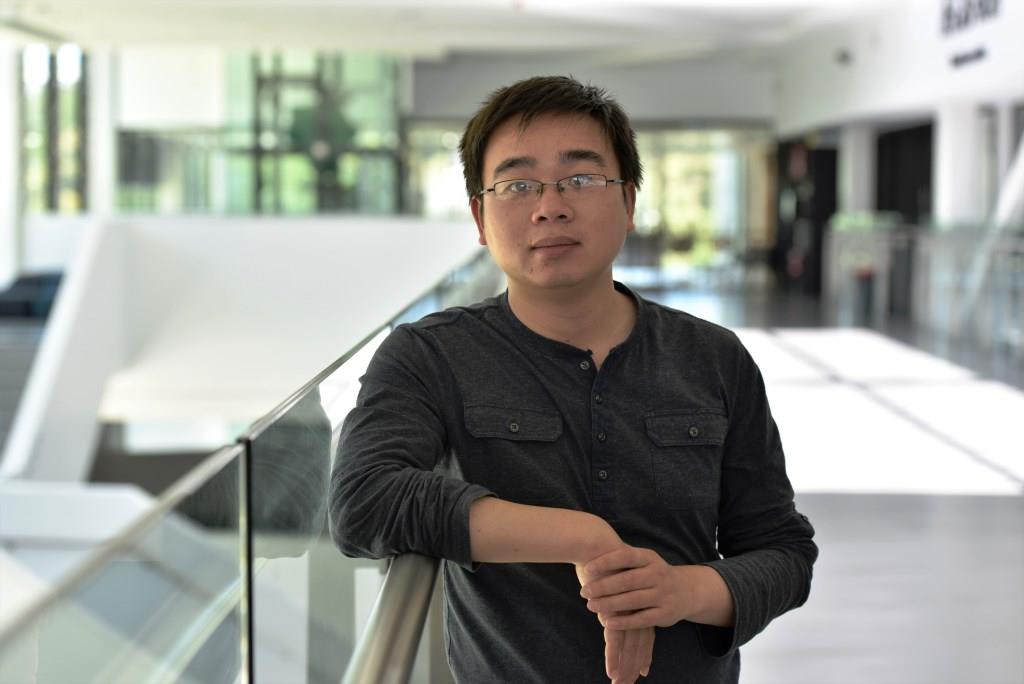

“The short-term negative peer effects generated by low achievers can fade out in the longer run,” write authors Dr Rong Zhu and Professor Bin Huang, who are based at Flinders University and the Nanjing University of Finance and Economics respectively.

To find low-performing students for the study, the researchers picked children who’d repeated a grade. They say repeaters appeared to reduce their peers results in two ways.

“Firstly, in Year 7, repeaters made middling students less likely to make friends with their high ability peers,” says Dr Zhu. “Secondly, they had a negative effect on the classroom environment. Peers of low-performing students were less likely to say their classmates were friendly, or that they got along well with them.”

“On the other hand, repeaters didn’t seem to have any major effect on their peers’ efforts to study, or on the quality of teaching.

“And by Year 9, they didn’t have any significant effect on their peers’ grades.”

Dr Zhu and Professor Huang suggest this may be because by Year 9, academic pressure was piling on ahead of high school entrance exams, and students’ approach to class and friendships shifted.

“With increased academic stress, students may change the way in which they interact with classmates,” they write. “Relative to repeaters in the seventh grade, repeaters in the ninth grade report improved class/school learning environment.”

“Compared with regular students in grade seven, those in grade nine tend to increase interactions with best academic performers and hardworking classmates, and low achievers may voluntarily or involuntarily improve their behaviours and be less disruptive in the classroom.”

The research took place in China, and the effect in each grade will relate to the local context. However, given their huge sample size and careful methods, say the researchers, educators and parents in other countries should take heed.

Dr Zhu says that he and Professor Haung, economists by training, took pains to screen out factors that might muddle the causal links in the study.

For example, their study only considered students who’d been randomly assigned to classes – a common practice for students entering Year 7 in China – to make sure the effects they observed weren’t really caused by family factors or school choices linked to the presence of lower performing students.

“The adverse peer impacts barely vary with regular students’ background – including gender, parental education, and whether they’re a rural student,” say the researchers.

One of the reasons they picked children who’d repeated a grade, says Dr Zhu, is because repeaters were unlikely to have shared a classroom with their Year 7 peers previously, cutting out conflating factors. And repeating a grade was a good indicator for ongoing academic struggles, he says, since these students typically had much lower academic achievements in Chinese, English, and maths.

The Year 7 peer effects were strongest in Chinese, and weakest in maths. They were worst in big classrooms.

Bin Huang & Rong Zhu (2020). ‘Peer effects of low-ability students in the classroom: evidence from China’s middle schools’ has been published in the Journal of Population Economics

This article was prepared by MCERA, an independent, not-for-profit organisation which raises public awareness of education research and researchers in the media.