Letters and books from Captain Matthew Flinders have been recently donated to the National Archives of Australia, which Flinders University historian Dr Gillian Dooley says highlights “two sides of Matthew Flinders”.

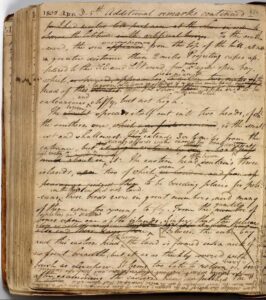

On the eve of Flinders’ birthday (16 March 1774), these items provide valuable fresh insight into Flinders’ curious nature and character – especially Flinders’ copy of British editor John Hawkesworth’s 1773 collection of accounts of four voyages to the Southern Hemisphere, which included James Cook’s observations of longitude along the east coast of Australia.

“Interestingly, Flinders recorded his corrections to Cook’s observations in the book’s margins, explaining in a later memoir that Cook was working with less sophisticated equipment 30 years earlier. But he was uneasy about it,” Dr Dooley says.

“He wrote, ‘If the corrections shall be found to approximate to the truth I shall be excused; if it should prove otherwise, I shall never excuse myself.’

“He also noted some words from the language of the First Australians in King George Sound in Western Australia, alongside Cook’s vocabulary from the east coast, demonstrating his awareness (also noted in his ship’s log) of the differences in the Australian languages.”

Another item to join the National Archives collection is a letter Captain Flinders wrote to his wife Ann’s teenage half-sister, Isabella, in April 1801, shortly after Flinders’ marriage.

“Isabella, or Belle, was much younger than Ann and when Flinders left England in July 1801, she was there to see him off,” notes Dr Dooley, author of Matthew Flinders: The Man Behind the Map.

“Isabella recalled the day in a later memoir: noting his uniform, ‘his cocked hat put slightly over one eye – his sword by his side – did he not look handsome?’

“This newly discovered letter shows that Flinders already had an affectionate and sometimes combative relationship with his teenage sister-in-law.

“These two items show the conscientious scientist, aware of his responsibilities to science and to posterity, alongside the affectionate family man who, while deeply in love with his wife, had a close and playful relationship with his in-laws.”

Belle wrote another letter to Flinders in 1810. Ann was still upset and missing him, but, Belle says, ‘for my part, if I were ever sure my husband would be taken abroad, and confined there for nine, or 10 years, I would marry tomorrow.’

Isabella never married, and lived with Ann throughout her long widowhood after Matthew Flinders’ premature death in Mauritius on July 1814.

Later buried at St James’s cemetery in London, Flinders’ remains were unearthed during an archaeological excavation preceding a major new railway development in January 2019 and his final resting place is due to be his birthplace Donington in Lincolnshire, England, in July 2024.

The Flinders Ranges, Flinders University, Flinders Chase are just a few of the important South Australian places named after the English explorer. Flinders’ and Baudin’s maritime explorations and detailed charts supported European settlement of the southern and western colonies of Australia.