This is a topic/question I’ve encountered a couple of times in the last 2 weeks.

The first was a conversation I had with some topic/course coordinators after a presentation I gave to STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) students about to embark on their PhD.

They told me about students who experienced significant depression after an experiment they were working on failed, or didn’t work out as expected. They said these students had their whole sense of identity and self-worth wrapped up in their work, in that experiment. So when the experiment failed, it was an indication that they were a failure as a person.

The topic then came up again at a workshop on perfectionism that I attended. Perfectionism is a clinical disorder that we see reasonably commonly in students where a) they set unreasonably high standards for themselves, b) they become highly self-critical and distressed when they don’t achieve these standards and c) they dismiss or minimise any actual achievements. The result is they feel constantly anxious about performance, commonly experience ‘failure’ because they set too high benchmarks for themselves and never experience the pride of having done well.

A related characteristic of perfectionists is that their long-term self-worth is wrapped up in achievements. Given the conditions above, you can see this is a recipe for disaster. If your self-worth is defined only by your achievements, but you never actually feel like you’ve achieved something because a) you consistently set the bar too high or b) you dismiss any achievements you do make, then you are destined to never feel worthy as a person.

These two experiences got me reflecting on the relationship between self-worth and study/work and I quickly realised this is a complex topic. ‘Sounds like a good blog post’ said a little voice in my head.

What is self-worth?

Self-worth is the subjective value you place on yourself. It is a combination of your beliefs about yourself (e.g. ‘I am a worthwhile person’) and your feelings about yourself (e.g. ‘I feel loved’).

Too little self-worth and you run the risk of getting depressed and hopeless.

Too much self-worth and you run the risk of arrogance and self-involvement.

Self-worth is related to a number of other ‘selfisms’

Self-confidence – the confidence one has in their own abilities

Self-efficacy – the extent to which one believes they are capable of certain actions

Self-esteem – the opinion you have of yourself

Self-worth can be represented as a global assessment of oneself – ‘I am a good person’ but can also be context specific. For example, I might think I have worth in terms of my work, but not think I am a good person in terms of friendships.

Sources of self-worth

Our sense of self-worth is assembled out of our experiences and our beliefs. This includes, but isn’t limited to:

- How people treat us

- Our upbringing and what we learned about ourselves from our primary caregivers

- Our religious or spiritual beliefs

- The talents and abilities we have that are recognised by others

- Formal recognition by others (e.g. awards)

- Our achievements

- Our ability to regulate our own emotions and behaviour

- Our capacity to influence how our life unfolds

- How connected we feel to the people around us

- A sense of belonging

- How engaged and connected we feel to the activities of everyday life

- Our connection with nature

- Our ability to have fun

- Our capacity for creativity and imagination

- Our capacity to work towards and achieve goals

- Our appearance

- Our capacity to learn new skills and acquire new knowledge

- Our capacity to cope with adversity

Some of these sources of self-worth are more robust than others, in that they are more readily available to us. For example, someone who believes that we all have inherent value, because of their spiritual beliefs has a more continuous source of self-worth than someone who relies on recognition from others.

We are also differentially sensitive to different sources. For some people, achievement might be what influences their self-worth the most. For others, it might be the sense of belonging with family and friends.

Why is self-worth important?

Self-worth is related to subjective wellbeing. Typically the higher one’s self-worth, the higher the wellbeing.

But more importantly from my perspective, is that self-worth is a key motivator.

If you believe that you have worth and value and capacity, you will be more likely to set and pursue goals.

Self-worth and students

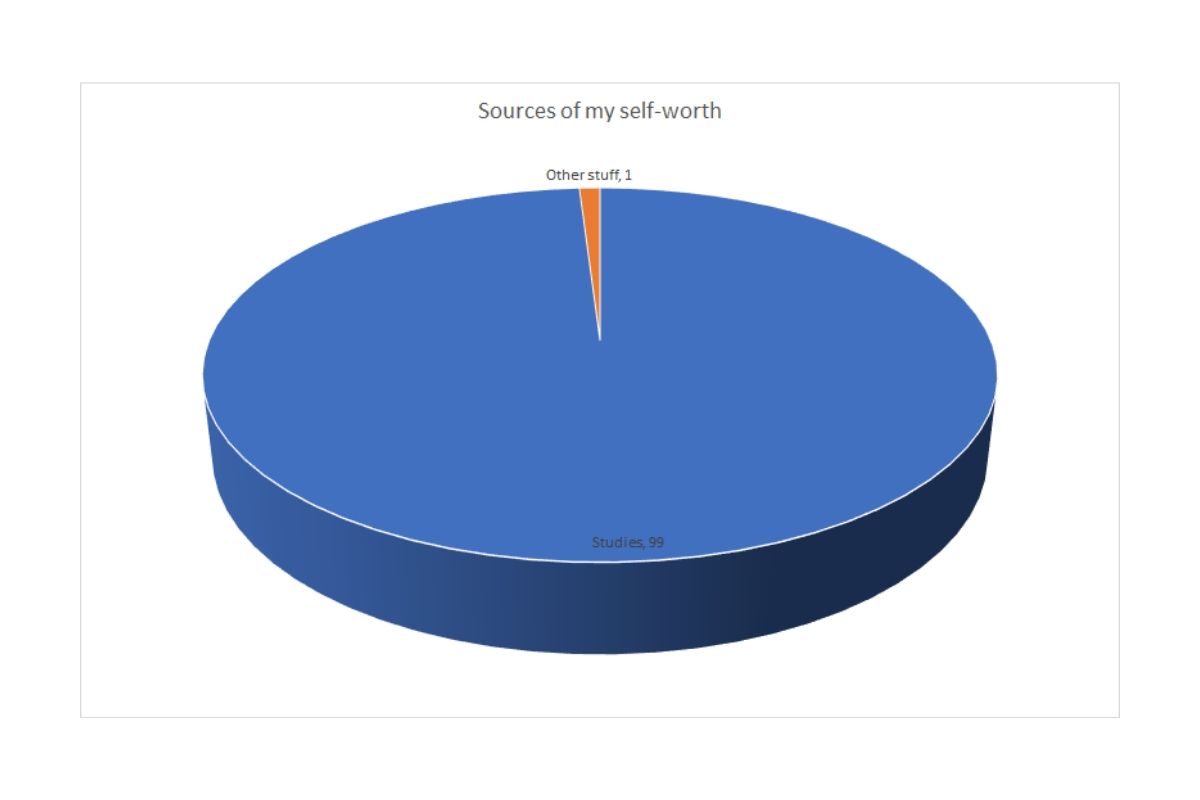

It is common for students to derive much of their self-worth from their academic study. It is why I wrote the ‘Evidence-based Study and Exam Tips‘ document – so that students can use psychological principles to boost their learning capacity.

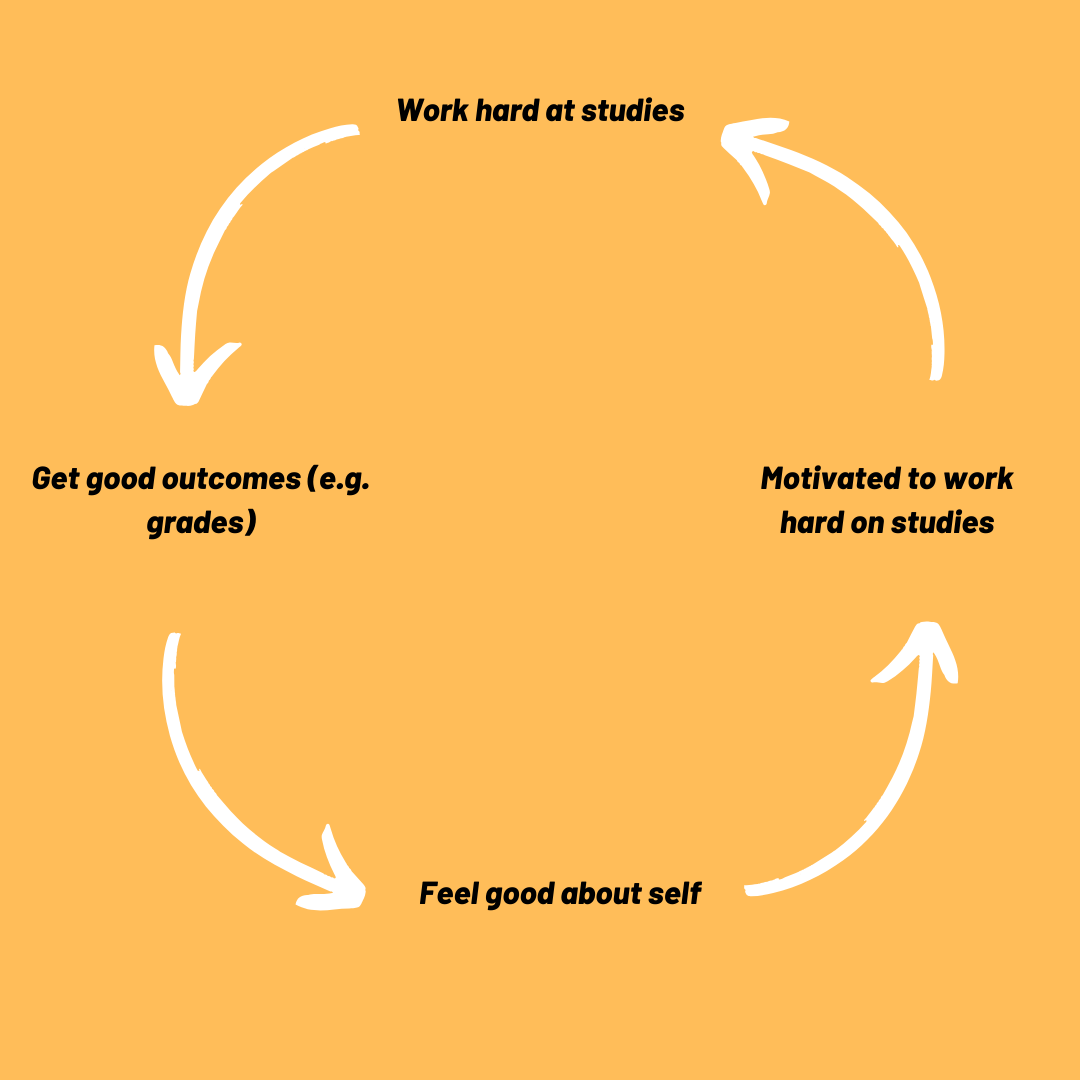

When this works well, it acts like a self-sustaining cycle that can lead to academic excellence.

However, if a student is deriving all of their self-worth from their studies, then this cycle can quickly go awry.

A couple of bad grades or assignments (or lab failures as suggested in the intro to this article) and the student can quickly lose faith in themselves, lose motivation and withdraw from their studies.

This is particularly the case for students who have had a long history of doing well academically. They are so used to academic success and the incredible boost this gives their self-worth that their first real failure at something academic is experienced as a massive gut-punch. Their self-worth spirals, especially if there aren’t other things contributing to their self-worth.

So how does one traverse this psychologically difficult space?

There are a few psychological tools/approaches that I think are helpful in this context.

Embrace failure – Failure is inevitable. For some students, experiences at university are the first time they’ve really experienced the feeling of failure. And I don’t mean the feeling of not being good at something. I mean the feeling of thinking you were good at something and then discovering you aren’t as good as you thought. That is the one that kicks you around emotionally – where your self-assessment of skill level doesn’t match your actual skill.

To embrace failure means to recognise that failure is a normal and required part of the learning process. The absence of struggle during learning breeds complacency. Those things that we struggle with, we ultimately learn better. Those things that we have to fight for a bit, we value more.

Failure is not an indictment that you have no worth. Failure is a sign that you are working at the edges of your knowledge and ability, and hence are in the best place for growth and development. Also, how you respond to failure will be information that you future self uses to assess self-worth.

Engage in self-compassion – Many of us (myself included) have come to believe that self-criticism is the most effective motivator. If I beat myself up for my mistakes, then I won’t make them again. But self-criticism erodes self-worth because your internal dialogue becomes focused on ‘not being good enough’, ‘not being smart enough’ etc.

Self-compassion is the antithesis to self-criticism and the evidence-based way to actually build productivity and wellbeing. It consists of a set of beliefs and actions that one takes, when confronted with setbacks or failures, to get back on track.

- Mindfully acknowledge that there has been a failure/setback and your role in that.

- Mindfully acknowledge that failures and setbacks are part of how people learn and are unavoidable and totally expected in the context of a complex interconnected world.

- Name and accept the presence of the suffering that accompanies the setback/failure (e.g. ‘this failed assignment has left me feeling embarrassed and stupid’).

- Expressing to yourself the same kindness you would extend to a close friend or family member in the same situation.

- Rather than ruminating on the emotional experience, map out how you might try to avoid a similar setback/failure in the future.

Self-compassion can build self-worth because it gives you a redemptive pathway and invites you to take that pathway. It gives you a uniquely human way back from the shame of failure.

Know your values – Values are descriptions of the person you want to be, the life you want to lead and the ways you want to live it. You can go online and find long lists of values, and scour them to find the ones (max 5-10) that best describe who you are now, and who you want to be moving forward.

Defining our way forward in life by values, rather than concrete goals has some advantages in terms of self-worth, especially for those students who tend to generate their self-worth on the basis of how well they are achieving their goals.

Let me try to explain the distinction.

Say you perused that long list of values that I linked to and identified that ‘learning’ was one of your top 10. You always want to be learning new things.

There are lots of ways you could manifest that value: formal courses/degrees, informal reading, mentorship, watching documentaries, attending public lectures, taking up a new hobby.

A goals-based person might say – ‘to indulge my love of learning, I need to start a university degree and get good grades (distinctions and above). They have a very concrete way of looking at learning. This is OK as long as they can achieve this specific goal. If not, they take a hit to their sense of self-worth.

A values-based person might say – ‘as long as I am engaged in a range of learning activities, then I am improving myself over time’. They take a much broader view of learning and recognise there are multiple ways to achieve this value and not to lock it down to just a single goal.

In reality, a mix of the two perspectives is best. It is good to set specific goals and work hard to achieve them. But it is also important to recognise that you can work towards who you want to be in many different ways and that goals will come and go, but the important thing is that you are moving towards those values. This gives you some psychological flexibility in being able to respond to individual setbacks or failures along the way.

Emotional acceptance – We tend to use our emotions as a guide on whether we are doing well. If I feel good, then I am doing good. If I feel bad, them I doing badly.

However they aren’t always the best guide. For example, at the time of writing, I am working hard to finish my Mental Fitness Workbook. The pressure of getting that done before Orientation 2020 is high and I am feeling the stress. If I were to use my emotional state as a guide to how I’m going at that task, I’d conclude that it is going badly. However, that isn’t the case at all. I am writing regularly, and putting it together slowly. I am on track.

We can make this same error with our self-worth. We can use our emotions/moods as a guide to whether we are a good person or not. Feel good = good. Feel bad = bad.

Emotional acceptance is a skill we can develop which helps us become more mindful and connected with our emotional state, but less reactive to it. One of the primary avenues to developing emotional acceptance is mindfulness training. I’ll speak more about this in the section below.

Adopt a growth mindset – A growth mindset says that improvement in any given area is more a function of deliberate practice, persistence and effort, than it is about natural talent. It isn’t that natural talent/ability isn’t important, it’s just that the human brain is set up to learn and improve with focused repetition (neuroplasticity) so we can take advantage of that when confronted with challenges.

A growth mindset is also more adaptive in terms of self-worth. Rather than base our self-worth on our natural abilities/talents (which we don’t really have a choice over), we can instead base our self-worth on our capacity to grow and improve (something which is in our control).

It isn’t easy to just shift mindsets. If you’ve spent a long time admonishing yourself because of a lack of ability/talent, then you aren’t just going to read this and suddenly have a new outlook. However, just knowing that humans have a tendency to judge their value/worth on ability/talent and discount the value of persistence and effort, is a good starting point. You might discover that you have this bias in thinking.

Self-as benchmark – When we evaluate our self-worth, we often use benchmarks (e.g. ‘I’m not as good as ‘X’). We also tend to choose benchmarks that are out of our immediate reach. For example, students often compare themselves to the most capable student in the class. This can have the paradoxical effect of de-motivating you, because the distance between you and the most capable student might be too far to traverse in a single step.

Thus, the best comparison point for you in your efforts to improve is yourself. What mark did you get for the last assignment? Can you aim in the next assignment to increase that by 5% or 10%. if you’ve just been getting passes, can you upgrade a few of them to credits?

Striving for incremental improvements over your previous level of performance is more protective in terms of self-worth. You are not setting yourself unrealistic standards and you are increasing the likelihood of you actually being able to show improvements over time.

This doesn’t mean you don’t set yourself the long-term goal of being as good as the best student in class, it just means that you efforts in the short-term are focused around making realistic improvements over your current level of performance.

Other focus – If you equate self-worth only with what you’ve achieved, you may be missing out on the psychological benefits of helping others.

When we assist others in achieving their goals, we get to practice vicariously all the techniques described above. We tend to me a lot more compassionate, accepting and helpful towards others than we might be to ourselves.

We also get the chance to experience self-worth arising from belonging and connection with others – something that can be ignored by those who have a very achievement focused way of looking at the world.

How does one develop those psychological capacities?

In relationships. In discussions with people you trust, where you can reveal the full extent of your victories and challenges in life.

These might be close friendships or family relationships where you feel free and safe to talk openly about what is happening in your life, as well as provide a space for the other person to do similar.

It might be in formal therapy or professional coaching where you are bouncing your life off a mental health professional.

It might be doing a group program (real-world or online) where you get to interact with other people trying to improve themselves. I’m working on a Mental Fitness Program at the moment that I hope to launch in 2020, where you’ll be able to join a community of other students working on their mental fitness.

It might be online forums.

It might mean getting a mentor (or even being a mentor). Getting mentorship has been one of the best things I’ve done in terms of my career and mental health.

The key is to open up conversations with people you trust and/or admire. In those sharing of experiences, you get the chance to trial different mindsets and perspectives that may help you gain insights into how to generate self-worth from multiple sources.

Final words

The value we place on ourselves is the result of a complex array of experiences over the course of our lives.

It is not uncommon however, to see students for whom their self-worth is tied up primarily in their academic performance. The post-university equivalent is the person who derives their self-worth entirely from their work.

This can be motivating and push someone to a high level of performance. But is a fragile state of affairs.

In relationships and sharing our life with others, we open ourselves up to perspectives that enhance our ability to generate self-worth from sources other than our studies/work. This is a more psychologically flexible way to be, and better prepares us for the inevitability of setbacks and failures in our primary area of focus.