The Preparing for Exams series was first posted in 2017. Each year now we update the posts and repost them as exams approach. Let’s face it, the rules for preparing for exams don’t really change that much over time.

A psychological tool is a way of thinking, behaving or interacting that produces a desirable outcome. Psychological tools are useful for a range of things. In this post I discuss 4 psychological tools I think have value as we head into the end of the year and exams. Reading time ~ 7 minutes.

As we head into exam season and end of year, you might be starting to accelerate your study activities.

As we push towards our goals, our minds aren’t always our best friend. For example, I’ve set out this week to improve my overall health a little and already I am fantasising about chocolate and Netflix marathons, neither of which will be particularly helpful in the health domain.

It might seem strange for our minds to play saboteur, but they weren’t really designed for modern life. We must drag them reluctantly into the modern age and develop psychological tools for managing their less-than-helpful tendencies at times.

Here are four tools which I will be discussing at a couple of exam preparation sessions with my partner-in-crime Grace over the next couple of weeks.

Non-sleep deep rest (NSDR)

This is a term coined by neuroscientist Andrew Huberman. It refers to a collection of activities (breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, meditation, yoga nidra, self-hypnosis) that have the unique capacity of providing both a calming/relaxation effect, along with a rejuvenation of focus capacity. They constitute an ideal way of breaking up long study sessions, especially under circumstances where sleep may be impaired.

Helpfully, Andrew has recorded a protocol for NSDR:

If this doesn’t tickle your fancy, I don’t mind this modernised Yoga Nidra protocol either.

NSDR isn’t just about taking a break from demanding activities. It is about the dual elicitation of calm (relaxation of the nervous system) alongside a focus on some aspect of our sensory experience (breathing, feeling of relaxation in the body, attendance to sensations). The combo seems to provide a rejuvenation effect similar to sleep. Those who use it regularly (e.g. once per day) say it is a critical piece of their productivity strategy, a piece that helps them find calm and rejuvenation when busy.

Cognitive distancing

Our minds produce a constant stream of thoughts, images, feelings, memories, beliefs, interpretations and judgements.

An eclectic mix, some of these constitute useful and relatively accurate assessments of the world, to help us navigate it better. Others are brain farts.

Humans (I’m not sure whether dogs 🐶 experience it or not) tend to believe their own thoughts. And this makes sense. It is confusing to think that one’s own mind would provide faulty or unhelpful assessments of the world. But minds do this all the time. Think how many times your mind has told you that something (e.g. an event) would suck, but then it turns out awesome. Think how many times your mind has told you unhelpful things about yourself that got you all demotivated, just at the point that you needed motivation instead.

I’m not saying that you shouldn’t trust your mind at all, but that it is a useful skill to be able to view some thoughts, beliefs, assessments and judgements with caution.

This capacity to step back from one’s thinking in order to determine if it is helpful or not is called cognitive distancing. The ‘cognitive’ part refers to thoughts/beliefs/judgements/interpretations etc. The ‘distancing’ part refers to weakening (where appropriate) the impact such thoughts/beliefs/judgements/interpretations have on us.

Two techniques are useful for cognitive distancing.

The first involves activating our inner detective 🕵🏼♀️ and examining whether our thinking is a) rational and/or b) helpful. For example, most times, after I have delivered a lecture or presentation of some sort, my mind throws at me a bunch of unkind assessments of how well I did (‘that sucked’, ‘they hated it’, ‘you know nothing’). My inner detective can look at each of these and ask ‘is that accurate?’ and ‘is that helpful?’. In some cases, the thought is just wrong (i.e. some people reported enjoying the presentation). Other times, the thought has a grain of truth but lacks nuance and precision (i.e. I might be able to increase my knowledge in an area, but it isn’t that I know nothing). Other times, the thought just isn’t helpful (i.e. ‘that sucked’ provides no valuable insights into what could be better). The detective can then offer a more accurate, nuanced and helpful assessment of the situation.

The second involves activating our inner zen master 🧘🏼♂️ and simply watching our thoughts/beliefs/judgements/interpretations arise and disappear, without getting tangled, hooked, lost in them. Kinda like climbing out of a river and sitting on the banks, watching the water flow, rather than diving in and being taken by the river. Those of you who have tried or practised mindfulness meditation will be familiar with the idea of observing one’s experience whilst resisting the temptation to get lost in it.

I like this sushi train metaphor

The inner zen master reminds us that difficult/unhelpful thoughts/beliefs/judgements/interpretations come and go, like clouds in the sky, leaves on a stream, buses at the exchange. We don’t need to react or respond to them. In the space that creates, we can ask ourselves, ‘how would I like to respond in this situation?’ ‘what would be a wise way of responding in this situation?’.

To give a more concrete example, imagine sitting down to study and being overwhelmed by self-doubt – thoughts and images of failure and lack of ability. To get tangled in that self-doubt might mean avoiding the study, distracting yourself with other tasks, giving up. Instead, your inner zen master would say “I’ve noticed thoughts of self-doubt showing up. You don’t need to become entangled with them. Instead focus on being the person you want to be and using this time to study”.

OK – so that sounds really easy when I write it, but I won’t pretend that it is that simple in practice. But, like any skill, regular practice makes it easier over time.

Psychological flexibility

It is worth noting that at any given point in time, we have competing motivations of what to do next. For example, when I wake up in the morning, I am usually captured immediately by a conflict between wanting to stay in bed, versus getting up and doing my morning routine (walking, journaling etc). The internal battle rages for a while whilst both sides put forward their best arguments.

So, when you sit down to study, that course of action is likely competing with the motivation to do other things (e.g. TV, YouTube, playing with pets, housework).

Depending on how challenging you perceive the study task to be, the motivation to do the other things might win out and you find yourself procrastinating.

The capacity to stay focused on and moving towards a goal, in the face of other temptations, is called self-regulation. Procrastination is sometimes called a failure of self-regulation.

Psychological flexibility is a psychological skill we can develop that is useful at these times where we have a choice to stay connected to a task that is important to us, versus being distracted by other options.

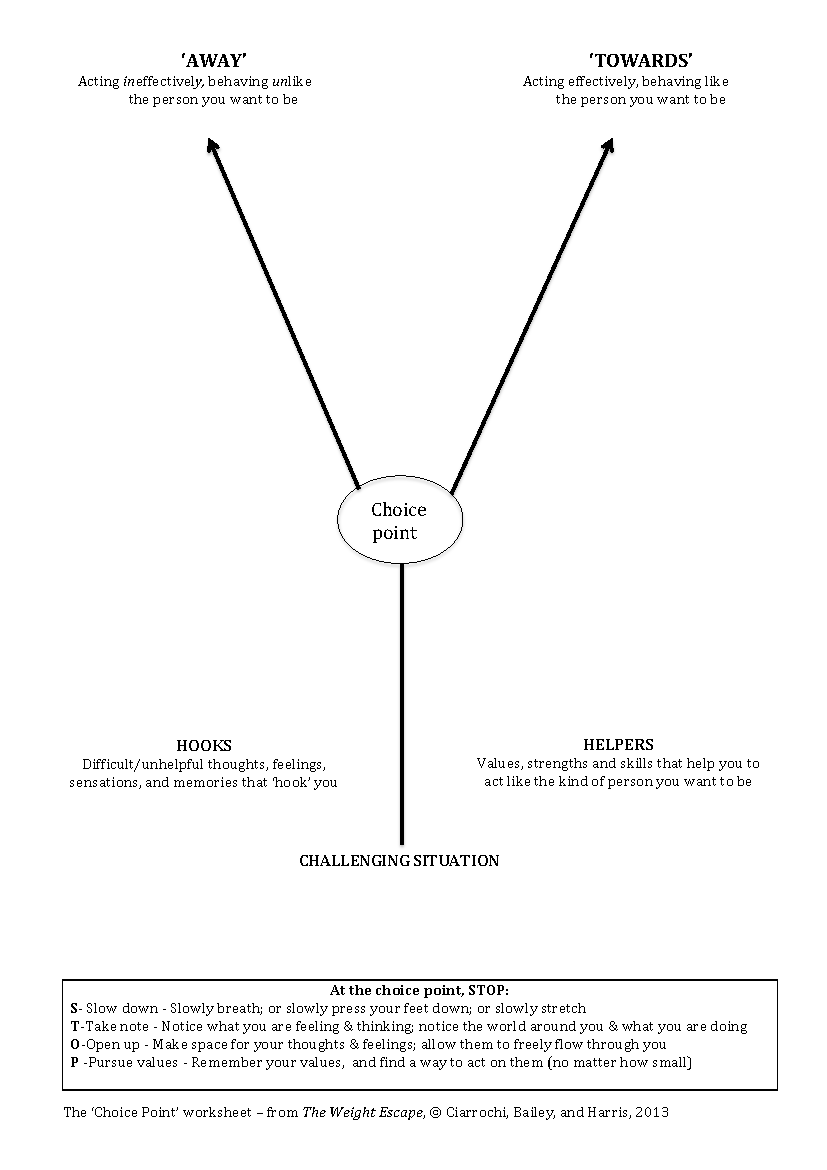

I think this handout from the Act Mindfully website by Russ Harris captures the whole process wonderfully (illustrated below).

Psychological flexibility is the set of instructions at the bottom. They are what to do when we are confronted by a choice. Let’s use a study example.

You wake up one morning and you have a couple of hours before a work shift in the afternoon. The person you want to be is the person who uses that time to work on an assignment or study for an exam. But your internal dialogue (“I’m tired, I don’t really want to study, I’d rather have fun, that assignment is hard”) and desire for short-term satisfaction mean you end up watching TV instead. That moment before you decided to watch TV instead was a choice point. We have many of these each day. Moments where we can choose ‘towards’ moves or ‘away’ moves.

At those points, the instruction is to:

S – Slow down – Slowly breath; or slowly press your feet down; or slowly stretch

T – Take note – Notice what you are feeling & thinking; notice the world around you & what you are doing

O – Open up – Make space for your thoughts & feelings; allow them to freely flow through you

P – Pursue values – Remember your values, and find a way to act on them (no matter how small)

Psychological flexibility is the combination of these four moves. It creates a little psychological space in which we become more acutely aware of the competing motivations and make a wise choice in the face of them.

As you prepare for exams, you’ll have many of these choice points. Times where you could study but will be tempted to do otherwise. Practice these four moves at those times. See if it helps create a bit of space in which you can make wiser choices than if you just mindlessly followed your impulses.

Self-compassion

In the pursuit of our goals, especially bold and ambitious ones, failure and setback are inevitable.

How we talk to ourselves at those times can influence how well we cope with the failure and how quickly we bounce back.

Most of us have a self-critical voice in our heads. It can be useful at times, especially if it is assessing our choices and working out where we might have made poor choices.

But that self-critical voice tends to overstay its welcome. It moves from telling us what we did wrong, to telling us that we are bad, stupid, unlovable, incapable. At that point, it goes from being useful, to instead just leaving us curled up in a ball, ruminating over how shit we are, which isn’t the best coping strategy.

Developing a self-compassionate voice is like developing the capacity to talk to ourselves in the same way that a friend or loved one might talk to us when things get hard. Generally, if we tell a good friend about a failure or setback, they are much kinder to us, then we are to ourselves (if they aren’t, get a new friend). We can learn to treat ourselves in that way.

I just published another blog post that describes how to develop a self-compassion script. If you are interested in boosting your capacity for self-compassion, that activity might be of value. Essentially it involves developing an affirmation/mantra that you rehearse and deliver to yourself when things don’t go to plan. It may feel artificial to do this at first, but it provides a good counterpoint to self-criticism and reminds us there are ways to speak to ourselves that are more helpful.

Psychological tools

If you want to learn more psychological tools for wellbeing or productivity, keep perusing the blog. You’ll find other similar articles to this one. I also suggest you register for a Be Well Plan in 2023. You can learn about the program at this post. To register your interest, email me – gareth.furber@flinders.edu.au – and I’ll add you to the mailing list for 2023.

Remember, I am talking about these and other study tools with Grace at a couple of exam preparation sessions on the 26th and 31st October.