Unpleasant emotions such an anxiety, fear, sadness and confusion, whilst undesirable, can provide powerful insights into our personal insecurities and if studied, can provide strong avenues for personal growth.

In this post, my goal is to give you a more detailed understanding of how strong emotional reactions come to be.

Based on this understanding we will then explore in future posts, the various strategies that can be used to manage powerful unpleasant emotions.

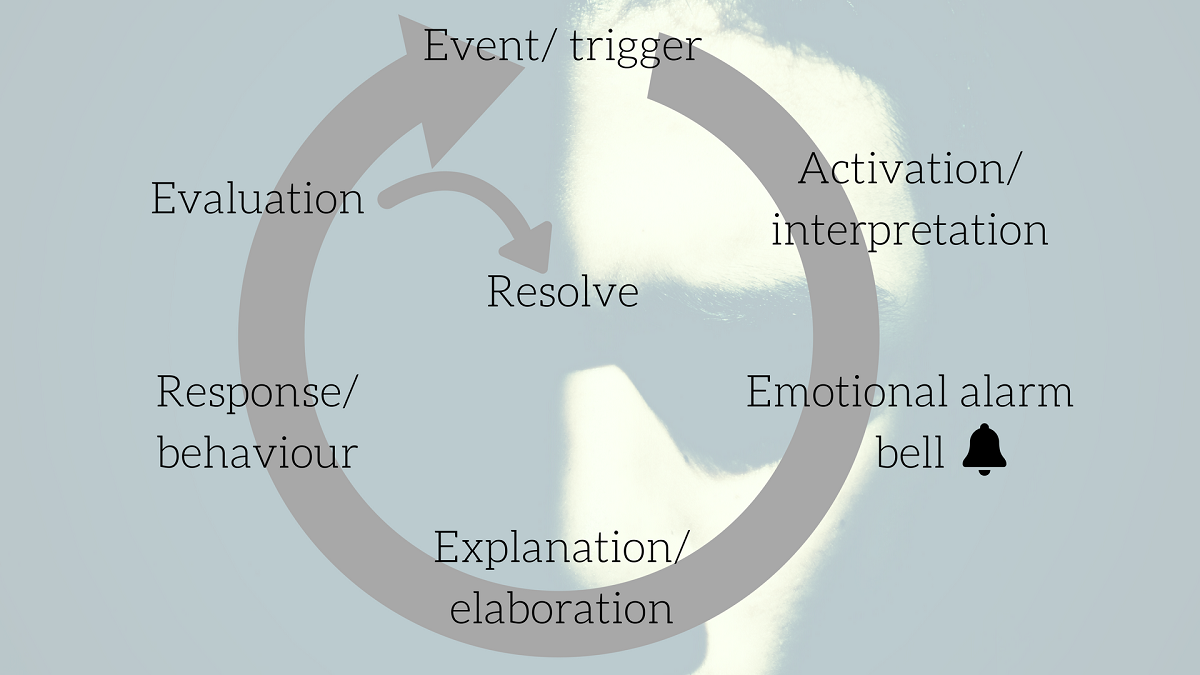

I’ve represented the experience of a powerful unpleasant emotion as consisting of 7 steps, summarised in the above diagram. Lets look at the individual stages.

Event/ trigger

All powerful emotional reactions are triggered by some event.

It might be an event external to you (e.g. something someone says, something that happens to you), or something internal to you, like a thought, memory, or physical sensation. I used to get quite distressed when I sensed digestive distress, because I believed it portended illness.

Some events are clearly expected to trigger strong emotions. These include traumas like sexual or physical assault, abuse, serious accident or illness, experiencing or witnessing violence, exposure to natural disasters, severe bullying, displacement, grief/separation, or exposure to war or political violence.

In other cases, the trigger can be, on the surface, relatively banal or minor.

For an event to trigger a strong unpleasant emotional response, it needs to be interpreted as a negative event.

Activation/ interpretation

Our brains are constantly taking information in from the senses and making judgments about the importance of the information.

As we go about our day, events activate memories, thoughts, beliefs, and images which our brain puts together in some kind of interpretation. A lot of this is out of your awareness.

In fact, our brain is a highly efficient and powerful pattern recognition engine. For the most part, it works really well. When we see food, we know its food. When we see traffic, we know not to step out on the road. When we see bad weather, we know to grab a raincoat.

A lot of the information coming in from our senses is deemed irrelevant or neutral.

When traumatic things happen to us, our brains quickly and correctly assess these as dangerous or harmful and trigger an alarm (see the next step).

But our brains can also assess some much less severe or even seemingly neutral things as dangerous and harmful.

Often this is because of the unique associations we have developed between the event/trigger and painful/upsetting memories, previous traumas, or ever-present insecurities we have. For example, for some people, receiving criticism might trigger memories of a hypercritical parent. Someone making a joke about our outfit might trigger insecurities we have about our body. Seeing someone from our past might trigger memories of abuse at the hands of that person.

Finally, sometimes brains make catastrophic interpretations, even when nothing is particularly going wrong.

Regardless of whether the event is traumatic or not, if the brain interprets it as so, it sets off alarms.

Emotional alarm bell

This is the part we feel.

So whilst it is probably not quite correct, I like to think of unpleasant emotions as a type of alarm system.

Like an alarm system, when they go off, they aren’t particularly nice (e.g. loud, jarring) but they are attempting to tell us something is wrong.

Unpleasant emotions, athough undesirable, do have a specific purpose. They are there to motivate us to take action to address whatever is wrong.

Think about some of the different unpleasant emotions and the action they might be trying to motivate us to take.

Anxiety or fear is trying to motivate us to escape

Anger is motivating us to fight

Sadness is motivating us to remove ourselves for the purposes of recovery

Confusion is motivating us to seek clarity

And emotions can be very motivating. Take fear for example, which motivates us to escape. It floods our system with adrenaline to get us moving. Incredibly helpful if faced with a genuine danger.

Also consider the feelings of grief following the loss of a loved one. The powerful sadness forces us to simplify and focus our immediate attention in order to start mourning the loss of that person.

The difficulty, as you might be starting to put together now, is that if the brain’s interpretation of the danger of the current event is incorrect, then we are stuck with an alarm going off that is motivating us to respond to a danger that might not be there.

Consider the case of those with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) for whom everyday situations or objects might trigger powerful memories of past traumas. They are not in immediate danger, but their emotional alarm bells go off indicating they are.

Explanation/ elaboration

The experience of a powerful unpleasant emotion is not just limited to the initial interpretation and the emotional alarm.

Our brains then try to elaborate on what is happening by activating other memories, thoughts, beliefs and images that are associated with the emotion and the initial interpretation. These are to support the original interpretation and emotional response and provide a clear explanation of what is happening and what to do next.

Again, in the context of a genuine trauma, this is helpful. The brain reinforces the level of danger, and strongly pushes for escape or fight.

But in the context of less severe events or triggering of previous trauma, it can seem like overkill.

Say you are upset about a failed assignment. Your brain has interpreted this as a disaster (perhaps because of unreasonably high expectations your parents have about your performance) and you are highly distressed.

Because your brain think this is a disaster, it elaborates on the initial interpretation and emotion by activating memories of other previous failures, or thoughts/beliefs like “I’m stupid” or “i’m lazy” or “I’m going to fail this course”. The intention is to make the event so salient that you avoid such situations in the future.

But the actual event is not a disaster. Minor failures are a normal part of life. The level of distress and self-criticism experienced ends up just making you more sensitive to perceived failures, and less able to cope with future failures.

Interestingly, as we will explore in future posts, the ability to determine when emotional responses reflect gross exaggerations of the seriousness of an event, versus an actual genuine trauma, is an important component of personal growth.

Response/ behaviour

How you respond to a strong emotional reaction plays a big role in whether the emotional reaction continues, or whether it resolves. It also plays a role in whether you will have similar reactions in the future.

In talking about these responses, I’m going to use the terminology of ‘positive coping strategies’ and ‘negative coping strategies’.

Positive coping strategies involve acceptance of the emotion, soothing or distracting attempts that ae not harmful and then thoughtful reflection on the experience and a problem solving approach to addressing any tangible problems of the situation or event that triggered the emotion.

In the case of the failed assignment example, this might look like:

- accepting that you are really upset about the assignment

- initially distracting or soothing self by watching a movie or having a long shower

- when feeling less distressed, reading the comments on the assignment carefully and understanding what you did wrong

- chatting to the course coordinator about the impact of the assignment and how you can do better next time

- practising or learning more about the specific things that went wrong with the assignment for next time

Negative coping strategies involve harmful efforts to squash the emotion (e.g. drinking), ongoing self-, or other criticism, avoidance of the situation, and no attempts to learn from the situation. The regular use of negative coping strategies increases the likelihood of similar emotional reactions in the future.

Note: in the case of highly traumatic events like those listed at the beginning, behavioural responses involving avoiding or escaping the situation ARE positive coping strategies. Once safety has been achieved, then it is the case that different coping responses can lead to different outcomes.

I’ll talk more in future posts about different positive and negative coping strategies.

Final evaluation

Even in the case of highly traumatic events, most big emotional responses resolve with time – the alarm system turns off (in the case of trauma or loss, this may take a while, as an extended period of grief or fear is a normal response).

We’re left then with a process of evaluation. I think of it as the ‘final report’ the brain gives on the experience.

The nature of this final evaluation I believe either sets us up to be triggered again, or reflects a genuine resolution of the issue.

Employing positive coping strategies and analysing the emotional experience more commonly leads to resolution. This is because we typically gain a better understanding of what happened, which aids us in the future in similar situations.

Employing negative coping strategies commonly leads to us being similarly triggered again in the future. This is because we avoid processing the emotion completely and revert back to strategies that provide short-term relief, but not long-term resilience.

Final words

In this post, I’ve explored the different stages of a strong unpleasant emotional reaction. In future posts, I’ll build on this understanding to explore the different ways that you can manage strong unpleasant emotions.

I should say that even though I’ve presented the process as a series of discrete steps, the experience of strong unpleasant emotions is typically more sudden and less ordered than what I have described. We don’t experience strong emotions as ‘going through a series of stages’, but understanding them in this way provides better clues for modifying them.

Got questions? – ask them in the comments below or email me: gareth.furber@flinders.edu.au

Till next we chat

Take care

Dr G