I’m building something (to be honest, I am always building something).

It is a program intended to help students get back on track with their learning and then sustain that performance whilst also attending to their mental health and wellbeing.

It is in the early stages at the moment but it is intended to be an expanded service offering for Health, Counselling and Disability Services.

As part of building it, I am thinking more specifically about the learning experience. How do you build something that is engaging and informative but also achievable/ manageable, especially for students who have fallen behind on their studies? There is no use creating a helping service that is more complex than the studies they are having trouble engaging with.

To learn more I have been delving into areas of psychology I haven’t previously explored. One of those is cognitive load theory. I am just at the beginning, but I recently read and took notes on a paper by John Sweller – https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11423-019-09701-3 called “Cognitive load theory and educational technology”. I thought it relevant as what I am trying to build is in the digital realm.

Whilst the bulk of what I took from the paper was for my purposes, there were some concepts/ideas that I think might be relevant to students. I thought I’d explore them in this post.

How complex the learning experience is will depend on how much previous knowledge you have of the topic

When you are dealing with totally novel information, you are going to have to bite it off in pretty small chunks first as you will be taxing your working memory, which doesn’t have a large capacity for novel information.

For information that needs remembering, break it into parts first (e.g. using flash cards) and then as you learn the individual chunks, start piecing them together. The more familiar you get with the material, the easier you will find it to start remembering it in larger chunks.

For complex tasks (e.g. writing an essay, complex calculations), you are going to want to start with some worked examples. See how other people have solved the calculation or approached the essay topic.

Warning: whilst accessing and analysing existing essays on a topic is a great way to learn how to write, it doesn’t mean you can copy those essays. Plagiarism is bad mkay.

Working memory might operate like a muscle and get fatigued 💪

When you are learning new material, you are pushing your working memory to its limits over an extended period of time. My understanding is that it fatigues as a result.

In the same way that you can’t indefinitely keep working out a muscle, you can’t indefinitely push your working memory. It needs time to rest.

What does working memory rest look like?

The most obvious is good quality regular sleep. I enjoyed this talk on sleep recently – warning, it is long, but very interesting – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nm1TxQj9IsQ

Other working memory rejuvenation methods include:

- Time in nature – even just 5-10 minutes of expanding your gaze out to looking at the sky, the trees, the birds, the mountains etc, can provide some restorative effects

- 5-10 minute breaks from learning where you just sit in a darkened room and let your mind wander (preferably not to the stuff you were just learning)

- Naps (not liked by everyone)

- Guided meditations, hypnosis, yoga nidra, relaxation sessions

- Find something on https://insighttimer.com/en-au

Essentially, periods of deep rest need to be intertwined amongst periods of deep learning for consolidation (establishing long-term memory) to occur.

Where information is transient take notes

An example of transient information is a lecture, where knowledge might be shared (i.e. spoken), but possibly not captured in notes/slides/recordings. Once the person has spoken the information, it is potentially lost.

I always recommend that students, if possible, attend lectures live, because there are ideas presented during such lectures that might not necessarily resonate or make sense in the subsequent notes or recordings. Furthermore, you lose the opportunity to ask questions in the moment.

When at lectures, try to capture that transient information in your own notes. Maybe it is a case example or an anecdote that the lecturer uses to illustrate a concept. These ‘examples’ can sometimes be what helps you grasp more complex theoretical ideas.

I’m quite sure that when I teach, many of my better ideas are found in the material I speak about that isn’t on the slide.

When pooling together your notes, combine diagrams and text

There seem to be some quirks to working memory that can be used to your advantage.

If you were trying to listen to two individuals talking on the same topic at the same time, you would soon be overwhelmed.

But if you listen to one person talking, but at the same time, view visual content (pictures, diagrams, photos) that are aligned with the verbal content, then you won’t be overwhelmed. In fact, you may even have enhanced learning of the material.

You can capture this in your summary notes (for revision) by including and interspersing written content and diagrams. In fact, if an idea can be represented visually, in many cases, it is superior for learning to represent it in that way.

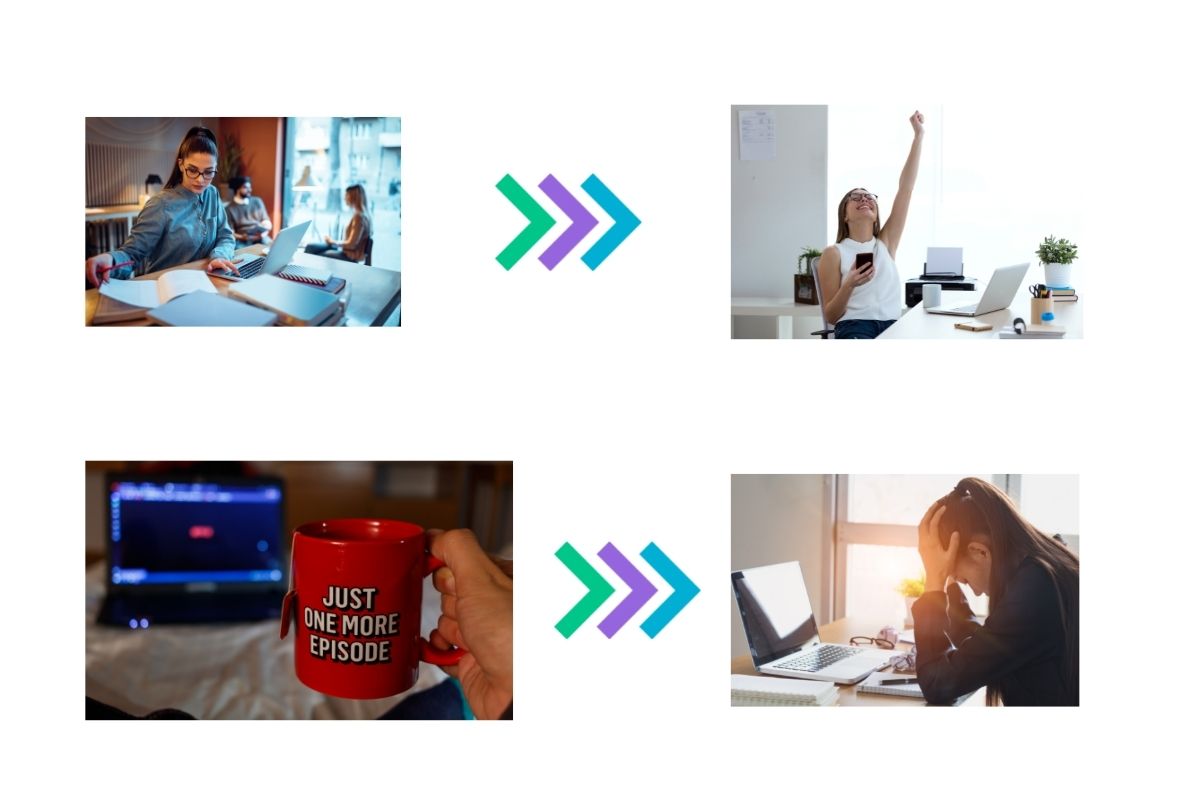

Diagrams are particularly good for representing processes or stages or steps or comparisons. Take this simple example, representing the benefits of study vs Netflix.

Pictures and diagrams are powerful memory aids, so use them in your notes.

Try pulling in all the relevant content to be learned into a single document

I remember revising for exams and having papers and notes and books lying all over the place. I’d be trying to remember something from a book at the same time as I was reading an article or looking at my notes.

Trying to split one’s attention across different documents can cause additional load on your working memory. If possible, try to consolidate what you need to learn into a single document that becomes the primary focal point of your learning.

Maybe this means taking screenshots of relevant book chapters and interspersing into your notes. The shift to most of our content being on laptops and electronic devices, makes it easier to create single documents that contain the relevant content to be learned.

An extension of this is also that if possible, try to limit your attention to a single item at a time. Most of us have other content open at the same time as we are studying (e.g. websites, email, social media, music, videos, etc). I am as guilty of this as anyone.

But try shutting down everything that isn’t related to the task you are doing right now. See if it can help create a little bit of mental room in which you can better focus on the task at hand.

For more study tips see our Evidence-based study tips document

We’ve been collecting together what we think are the best study tips into a single document. Yes, it is jam packed and maybe a little intimidating as a result, but have a read and see if there is just one thing you could change for the better about how you study.

Improvements to study habits are made gradually, piece by piece, as you develop a productivity system that works for you. Don’t fret about getting it perfect the first time. I continue to experiment and refine how I get my work done. It is simply a part of being in the modern workforce. Just commit to making small incremental positive changes to the way you work and get started whilst you are student, so you can enter the workforce with these habits already in play.