A lot of university students are unhappy.

At least that is the picture being painted by research over the past few years into tertiary student mental health (e.g. here, here)

As with all good meaty problems, the reasons are complex.

In their article “Academic and non-academic predictors of student psychological distress: the role of social identity and loneliness“, McIntyre, Worsley, Corcoran, Woods & Bentall sought to make this complex topic a little more accessible. This blog post is about their findings.

Spoilers: it has partly to do with students not feeling like they belong.

What is the problem?

The basic problem is that high numbers of students are reporting high levels of distress but we don’t really know exactly what is contributing to this. Some students thrive at university, others suffer, so it is not a given that the issue is to do with just academic pressures.

McIntyre et al. suggest we need to consider all the various stressors on students to understand why they might be struggling. This includes financial pressures, academic pressures, and relationship stressors (i.e. family, romantic, peer, faculty relationships). We then need to balance this with the various supports available to students such as their fellow students (peer support), their psychological strengths (e.g. self-esteem) and the practical services available to them (e.g. like HCDS) .

Put simply, if the stressors outweigh the supports, then the students struggle (as a side note: this kinda means that if you are struggling, it might just be that your balance of supports to stressors is out of whack, not that you are broken)

For universities, this means that interventions to make students happier can address the stressors side of the equation, and/or the supports side of the equation. Knowing how important each of the factors are in predicting distress gives clues about where to intervene first.

McIntyre et al. hypothesised (based on previous research) that it is the relationships/social parts of the equation that is most vulnerable in tertiary students. When we feel that we belong to a group (or groups) and that group is successful, then it has lots of flow-on benefits for our health and wellbeing. Conversely, when we don’t feel like we belong to a group (or groups) or those groups are unsuccessful, this has negative impacts on our health and wellbeing.

The authors were interested in exploring this in some detail.

What did they do?

First – they did a big survey. I love a big survey.

Their target population was 1135 UK tertiary students with the following characteristics:

- health and life sciences (30%), humanities and social sciences (42%), Science and engineering (18%)

- first year 46%, second year 35%, third 21%

- mostly white (82%)

- mostly female (72%)

- average age 20.78

They asked them a lot of questions about: academic stress, expectations, relative performance, loneliness, social identity, living conditions, financial worries, perceived discrimination, cybervictimisation, childhood disadvantage, maltreatment, paranoia, depression, anxiety, and self-harm/suicidal ideation.

They then did what is one of the great joys in life; to take this massive pile of independent and dependent variables and throw them into some regression equations. Honestly, if you’ve never thrown a ridiculous number of variables in a regression equation, you haven’t lived.

What did they find?

Consistent with the broader literature, they found many students who were struggling. Using ‘moderate’ distress cutoffs, 42% of students had anxiety, 25% had depression, 22% had both.

Using ‘severe’ distress cutoffs 21% had anxiety, 11% had depression, 9% had both. 19% of students had had suicidal thoughts in the last 12 months; 20% had self-harmed at some point, 12.1% had had a lifetime suicide attempt, 2.5% a serious determined one.

What about those regression equations you were getting all excited about?

So here’s the thing. If you throw lots of things into a regression equation, you get lots of things out. So I am only going to deal with the bigger findings.

Consistent with the predictions of the authors, social identity – which is the extent to which an individual identifies with, and feels they belong to a specific group – and loneliness, were powerful predictors of symptoms of depression, anxiety and paranoia. Let’s unpack that a bit.

The authors looked at the extent to which students felt they belonged to a number of ‘groups’: country, England, the city, the university, their primary online community and their university friends. It was the extent to which students identified with, and felt they belonged with their university friends that was the most important.

The less students identified with a friendship group, the more lonely they were, and the poorer their mental health.

What does this mean?

Universities provide many opportunities for meaningful social connection.

But there are also a number of reasons why students might not be able to take full advantage of these. Students studying primarily online might find it hard to build friendships in the absence of physical presence. International students may take a while to adjust to the new culture. Mature age students might struggle to find common points of connection with younger students.

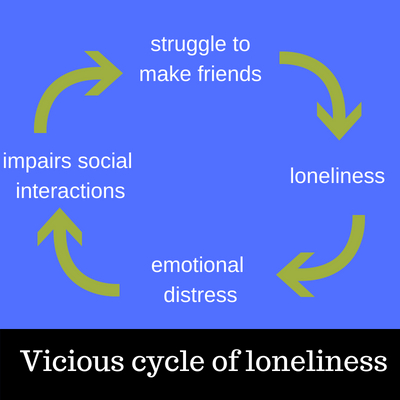

Whatever the reason, studying at university, without the peer friendships and connections can be isolating. This can end up as a bit of a vicious cycle.

The authors suggested focusing on building connections with smaller, goal focused groups. These can be a little lower pressure socially, because the purpose of the group is already defined.

For example, you might join one of the many clubs here at Flinders, based on your interests.

You might start a small study group, with students from your degree. This can benefit you socially, but also academically. Not sure how to do that? – try this set of instructions.

Health, Counselling and Disability Services/ OASIS run a number of small group activities that might be a good starting point: Mindful Yoga, Studyology, Meditation.

Finally the Horizon awards program runs a lot of ‘professional development’ events, where you can meet like-minded students trying to improve their work-ready skillset.

Takeaway message

Isolation and loneliness are powerful predictors of poor wellbeing for university students. Making more social connections can help heal those students feeling unhappy in their university experience.

Clubs, study groups, wellbeing programs and professional development events are good starting points for making such connections because they are very goal focused and less challenging socially, than simply trying to ‘make new friends’.