Greetings and welcome to Lesson 14 of my ‘Introduction to Mental Fitness’ course. If you are new to the course, check out the introductory post first.

Also a quick reminder that for Flinders students, these lessons can found on our FLO site as well, where you can chat about these lessons privately with other students, as comments left on this blog are visible to the general public.

Over the past few lessons I’ve been encouraging you to make a small lifestyle change, as a mental fitness experiment. I’ve been modeling this myself by trying to increase my time using my standing desk.

Practicing making positive lifestyle changes helps you achieve at least two things:

- First, if implemented successfully you get the positive impacts of the lifestyle change itself. So if you decided to spend 15 minutes each day out amongst the trees, then you will get the benefits of that particular change. These might include a lift in mood or feelings of relaxation or a feeling of interconnection with nature.

- Second, you get better at making lifestyle changes. This is a valuable set of skills that you can then apply to other aspects of your life. For example, in the process of setting aside 15 minutes each day to spend in nature, you would have picked up some skills about how to make a lasting change in your behaviour. You can then apply this knowledge to making other changes in your life (e.g. physical activity, diet, catching up with others).

Both sets of outcomes constitute an improvement in mental fitness. In one, you’ve developed the capacity to alter your mood and sense of connection through time in nature. In the other, you’ve developed further your capacity to make positive changes in your life.

These are not insignificant changes either. If you accumulated small changes like these over time, you could quite dramatically alter the overall experience of your life.

Therein lies the power the of the mental fitness model. A method for making incremental and targeted improvements in your life over time.

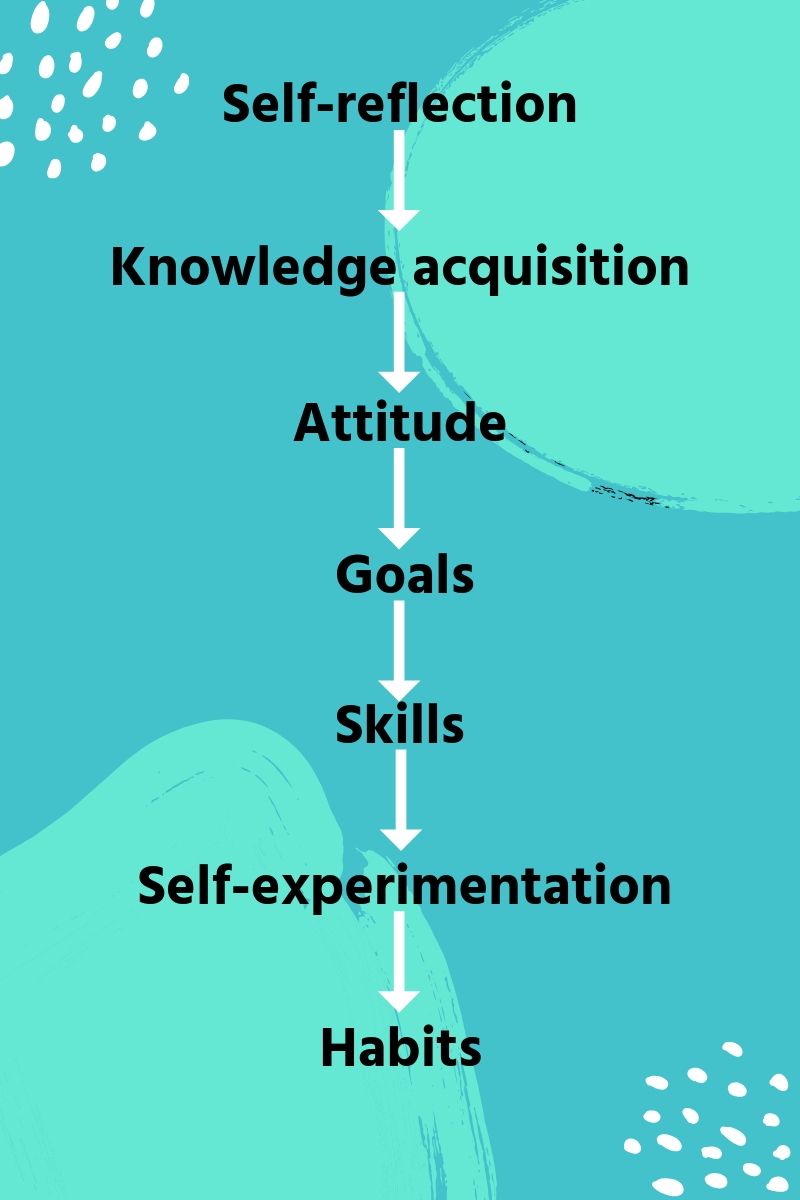

Let’s revise quickly what we’ve covered thus far

We essentially started this process in Lesson 8, when in the Suggested Tasks section I asked you consider a skill area you might consider working on. In Lesson 9, I went further and suggested you identify a simple lifestyle change you wanted to make. Essentially this was a process of self-reflection.

In Lessons 10, 11, 12 and 13, I then explored the various activities that one would go through in making such a lifestyle change. This included educating yourself about the intended lifestyle change, setting goals, developing the necessary skills required to make the lifestyle change and then conducting a self-experiment to see if the lifestyle change in indeed beneficial.

Thus far I’ve presented these activities as though you move through them in a linear way.

In reality, I don’t think this is the case.

In the process of making an important lifestyle change, you are likely to cycle through these or be tackling two or more at a time.

To illustrate, when I’ve made changes to my diet in the past, I’ve typically been educating myself and trialing changes at the same time.

However, discussing each one separately can help illuminate that the process of making important lifestyle changes is multi-factorial.

Today’s post is about the end-point of that process – habits

A habit is “something that you do often and regularly, sometimes without knowing that you are doing it“.

As you can imagine and have probably experienced, people have good and bad habits. I have the good habit of brushing my teeth. I have the bad habit of regularly buying and eating potato chips.

Habits can be observable behaviours (e.g. grabbing your hat off the hat rack before leaving home) or unobservable mental behaviours (e.g. frequently interpreting constructive criticism as a personal attack).

Our mix of habits shapes our life. If your good habits > bad habits, then you’ll tend towards health and wellbeing. If your bad habits > good habits, then you might tend towards illness and suffering.

You can look at mental fitness as the process of a) getting good at establishing mentally healthy habits and b) establishing enough mentally healthy habits to improve your psychological wellbeing.

I would argue that most long-term, sustained improvements in mental and psychological health result from the establishment of mentally healthy habits.

Consider an individual who presents for help with their anxiety. They see a psychologist for 12 sessions. During those sessions the psychologist teaches them a range of anxiety-management strategies. These include breathing exercises and cognitive strategies that the individual uses to challenge their irrational thinking. The extent to which the individual makes improvement over time will be a function of the whether they make those strategies a part of their life. Do they make focusing on their breathing and checking their thoughts a part of their daily life?

Now I’m not suggesting that the entirety of our health and wellbeing is the result of our habits. Other factors like environment and genetics play a big role. But habits are something we can control and that we know will impact on our health and wellbeing. They are a pathway to health and wellbeing that we can utilise and harness.

How to make something a habit

If you’ve been following previous lessons, you’ll know that I’ve been using the example of ‘spending more time using my standing desk’ as a lifestyle change that I want to make.

I started with broad goal of reducing my sedentary time, educated myself on the literature on standing desks, set myself a specific goal of 5+ hours standing per working day, and have been experimenting with that ever since. I’ve found that the benefits (increased energy levels, reduced sitting time) outweigh the costs (mild foot and leg pain).

I can now reliably do 5+ hours of standing work each day. I’ve made the decision that I want to continue using my standing desk. My job is to now make it a habit – something that I do pretty much automatically each day. I don’t want to have to keep thinking about using my standing desk. I just want it to become part of what I do everyday.

That is where this handout comes in handy.

Many years back, I came across the work of Susan Michie and colleagues. They’ve spent an incredible amount of time and effort trying to understand the processes by which people make positive lifestyle changes, particularly in relation to health. Admirable work, because it is actually really hard to do.

I took their early work and built this handout on habit building strategies. Essentially I extracted from their work strategies that have been used in health interventions to get people to change their behaviour. These strategies aren’t guaranteed to help you build a new habit, but their presence should convince you that there are actually many things you can do to support a new behaviour becoming a habit.

If you had a behaviour (e.g. lunchtime walk) that you wanted to turn into a habit (i.e. a daily lunchtime walk), you could try the following:

Goals and planning – set a goal of daily lunchtime walks, make a public commitment to do so and make a detailed plan on how you will achieve that goal.

Feedback and monitoring – set up systems to track whether or not you are doing a daily walk.

Social support – get other people to help you engage in your daily walk by reminding you, or joining you for the walk.

Shaping knowledge – learn as much as you can about the benefits of daily walking as you can to motivate you.

Comparison with others – observe closely the behaviour of others to determine if they do, or do not engage in daily walks. Try to copy or learn from those that do.

Associations – set up reminders (e.g. an alarm) to engage in the daily walk. Associate the daily walk with a habit you already have.

Repetition and substitution – keep engaging in the daily walk until it becomes automatic. Replace a bad habit with the daily walk.

Comparison of outcomes – contrast your life with the walk, with your life without the walk.

Reward and threat – set up rewards for successfully going on a daily walk. Remove privileges if you fail.

Emotional regulation – find alternative ways of managing the inevitable ‘I don’t feel like walking’ that will come up.

Antecedents – set up your life so it is easier to engage in the daily walk (e.g. have sneakers in your office).

Identity – build the habit into how you think about yourself as a person – ‘i’m a walker’.

Self-belief – use positive self-talk and self-compassion to remind yourself that you can make daily walks a habit.

Covert learning – use your imagination to picture yourself being someone that walks daily.

I go into a little more detail in the handout on each of these strategies.

How long does it take to establish a habit?

You might like this article. Spoiler: anywhere between 2-8 months.

Reflection Question(s)

Think about habits you already have such as brushing your teeth, your morning coffee, your TV watching habits.

How did those habits get established? What keeps them going? Can you learn anything from those habits that you could use when trying to establish new mentally healthy habits?

Suggested Tasks

If you’ve been following along with the tasks from previous episodes then you’ll have identified a lifestyle change you want to make, have educated yourself about it, practised building the relevant skills and set about planning an experiment to see if its introduction into your life would yield positive outcomes. You may have even started that experiment.

In this suggested task, I am going to make the assumption that the lifestyle change you’ve chosen is likely to beneficial and something you want to make into a habit.

I want you to review this handout on Building New Habits. I want you to select 5 of these to use in helping you establish your new habit.

As an example, I’ll reveal the strategies I am using to lock in my standing desk use as a habit.

- I continue to check in on the literature on standing desks to increase my knowledge. For example I found this article – Caldwell, A. R., Harris, B. T., Rosa-Caldwell, M. E., Payne, M., Daniels, B., Gallagher, K. M., & Ganio, M. S. (2018). Prolonged Standing Increases Lower Peripheral Arterial Stiffness Independent Of Walking Breaks: 2251 Board# 87 June 1 11. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 50(5S), 549 which suggests that prolonged standing can have problems that may need to be alleviated through further exploration of walking interventions.

- I focus on the fact that others are not using standing desks and use this false sense of superiority as a motivator.

- I start the day by raising my desk at 8.00am, lowering it at lunchtime (12.00pm) and raising it again after lunch (1.00pm). This association between time of day and position of desk has helped me use it a lot more.

- I built up slowly from 3 hours per day to 5+ hours per day. This allowed me to get used to the physical demands of standing for large amounts of time.

- I identify as a ‘standing desk user’ and regularly extol the virtues to other people.

Good luck!

In the next lesson, I’ll try and pull everything together we’ve discussed thus far. You might be surprised just how far we’ve come.