If you are reading this and it still the exam period or you have assignments in play, then I suggest putting it aside for later. This is the kind of post to read once you have finished up for the 2019 year.

Imagine that you were going to go for a day hiking in a area of dense forest.

You pack up everything you need: food, water, map, compass, first aid kid etc.

You arrive at the entrance to the forest in the morning and check-in with the park ranger (always good practice if you are hiking an unfamiliar area). You tell them your plans and where you’ll be and then set off for the day.

The first part of the day is really enjoyable. It is serene being in the forest and you feel invigorated.

In the late afternoon, whilst trying to cross-reference a feature of the land with an entry on the map, you realise that you might actually be a bit lost. Where you thought you were, and where you seem to be are two different places.

You start to freak out a bit. You don’t know when you made a wrong turn and now you can’t locate yourself on the map anymore.

Visions of being lost overnight fill your head.

As the anxiety builds, you remember the park ranger telling you ‘if you get lost, simply orient yourself North with your compass and follow that direction. You’ll eventually hit the main forest road at which point you can signal for help, or follow the road back to the ranger station’.

But you start wondering whether you could actually re-trace your steps and find your way back. You start imagining how embarrassing it will be to have to follow the rangers advice and admit that you got lost. You start berating yourself for sucking at reading a map.

At this point, you have two choices:

- follow the simple plan outlined by the ranger

- follow the emerging plan that your anxious mind is creating

Now the smart play is to follow the ranger’s advice. That advice was given on the basis of years of experience of people getting lost in that forest. It is a plan based on logic. It is a plan designed to override any other plans that a person might try generating in a moment of panic or embarrassment.

Many people however will follow the advice of their mind in that moment. Yes, some will succeed in getting back, but others will get even more lost, even more embarrassed, feel even more stupid.

What does this mean in relation to 2020?

If you are returning to study in 2020, I want you to think about your plan of attack for the year, before study kicks off and all the stressors of the year kick in.

What days will you study? What time will you start each day? How many hours will you study each day? When will you take breaks? How will you use those breaks? What will you do to rest and recuperate?

How will you study? Will you use flashcards? Will you take notes? Will you start a study group?

What marks would you like to get? What are you most interested in learning this year?

What other activities will you engage in to balance your life out? How will you fit those in?

Remind yourself of why you chose to go to university. Remind yourself that this is your stepping stone to a more interesting life. Remind yourself that completing your degree opens up new opportunities for you in terms of career and future goals.

Really take the time to think about how you are going to approach the year.

Yes, this is a lot of self-reflection, but the purpose of asking these questions and thinking about these issues now is so that, on that random Monday morning in April, when you wake up in the morning and your brain is telling you all sorts of other things:

- I can’t be bothered studying today

- I can put this off till tomorrow

- I can’t do this – I’m stupid

- It’s boring

- I’m too tired

- Why did I choose this stupid degree

- I think I need to take time to look after ‘me’

- No-one else seems to be working this hard

you will be able to remind yourself that there is already a plan in place, and that plan was put in place for your benefit, for your safety, for your best interests. The compass point has already been set and your job is to follow it.

Be prepared to defend your plan

There is something a little intimidating about meeting someone who has a clear plan and is trying to manifest it.

Therefore expect some responses to your plan that you might need to defend against.

Your friends might encourage you to be a little lax with your study routine. They don’t want you to fail, they just want to spend time with you.

Your family or friends might get frustrated at the time you are spending on your study. They don’t want you to fail, they just want to spend time with you.

Your classmates might lightly ridicule your attempts to stick to your routine. Again, they don’t want you to fail, they might just be a little intimidated.

Resist the temptation to deviate from your plan based on these pressures.

Instead, try to explain to those people why you have the plan, what it is you are working towards and what you want to achieve. If possible, find a way to include those people in the plan. For example:

- take a leading role in organising social events with friends

- use your conversation time with family and friends to talk about some of the stuff you are learning

- invite classmates to join you in a study group

Some people may end up being inspired by your commitment to your plan and look to do something similar in their own life.

The key lesson here is one of making decisions based on values, not on feelings

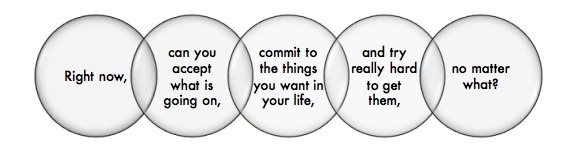

In Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), a model of therapy used to help people with a wide range of problems, there is a core idea that our choices and decisions in life should be made on the basis of our values (what is important to us and who we want to be), rather than our feelings in the moment.

This is a simple but powerful idea.

In any given moment, the decisions you make are highly likely to be driven by your thoughts and feelings at the time.

Whether I sit down to do an assignment on any given morning will be strongly related to whether I ‘feel like doing the assignment’.

ACT encourages us to instead make the decisions based on a higher set of values and goals.

The decision to do the assignment is not based on whether you feel like it, but whether doing that assignment moves you towards where you want to be in life: a productive person with a degree. The feelings in that moment need only be noticed, named, accepted and then relegated to the background.

I’m not pretending this is easy: to live a life based on values, not feelings. But it is a pathway of moving you towards what is most important to you.

Take home message

During the break, take the time to develop a study plan for 2020 that takes into account when you’ll study, how you’ll study, and how you’ll balance study and other parts of life. Include in that plan a clear statement of what it is you hope you achieve by the end of the year and how that relates to your life moving forward.

Put that plan somewhere visible as a reminder.

When your brain or someone you know inevitably shows up and tries to deviate you from the plan, remind them that you already have your compass point in place.