We’ve all had meltdowns.

We will all have them again.

They suck.

But they are normal.

Now despite my clinical background, ‘meltdown’ is not a clinical term. If I were to give it a clinical name, I might go with ‘response to an acutely stressful event’ or ‘an episode of severe emotional distress’.

But somehow ‘meltdown’ captures it better, at least for me.

A meltdown can range in severity from the relatively mild (i.e. something akin to a tantrum) to moderate severity (i.e. high level of emotional distress) to pretty severe (e.g. something akin to a full panic attack).

Meltdowns are typically reactions to acutely stressful events, typically things that come out of the blue and surprise us.

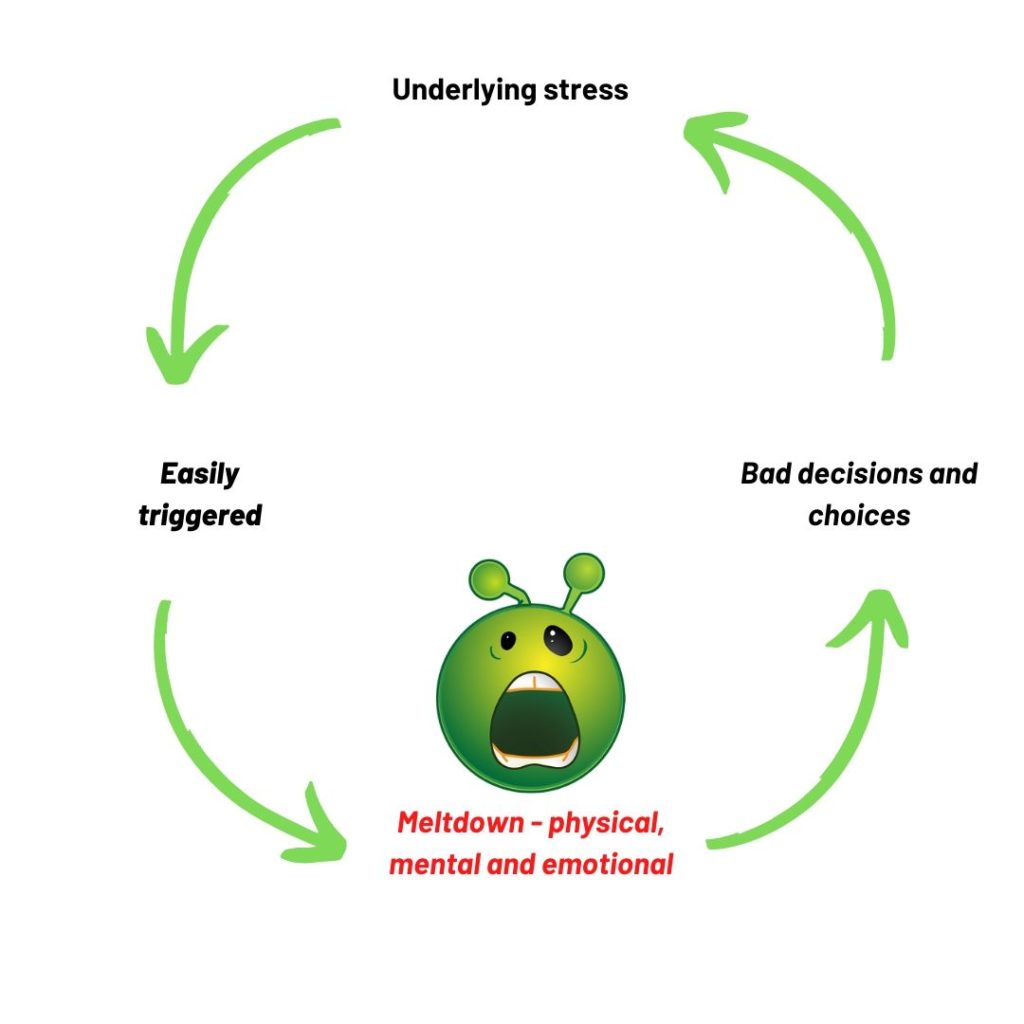

Meltdowns are different from the stress we experience in the presence of a chronic stressor (e.g. illness) but admittedly meltdowns are more likely to happen if something acutely stressful happens, on top of existing chronic stressors. For example, a student might be constantly stressed about being behind in their studies, but has a meltdown when they discover another assignment due that they had forgotten about.

The severity of a meltdown is not always (at least on the surface) directly proportional to the stressor. I’ve had major meltdowns over very small things (e.g. hitting my knee on a table). Usually in those cases, there has been a build up of stress over time, which is triggered by a relatively small setback.

Other times however, shitty stuff happens to us and it overwhelms us in the short-term. Cue: meltdown.

A meltdown is generally a full body and mind experience:

- There can be physical sensations like racing heart, feeling sick, muscle tension, short quick breathing.

- Our thinking goes all haywire – it becomes highly negative, highly critical. All logic and sense go out the window.

- We experience powerful, uncontrollable and unpleasant emotions such as fear, anxiety, distress, anger, sadness, despair.

- During a meltdown, we are far more likely to make bad choices and decisions and engage in self-destructive behaviours – say wrong things, self-soothe in bad ways, use drugs and alcohol

Thus a meltdown is a fully encompassing experience involving physical, cognitive, emotional and behavioural changes.

But before I talk about how one copes with or manages a meltdown, I want to address that the use of the term ‘meltdown’ could imply I don’t treat them seriously. That is definitely not the case. I’ve experienced and witnessed severe emotional distress (as most of us have) and wouldn’t wish that on anyone. I am however mindful that episodes of severe emotional distress are part and parcel of being human. Hence I used the term ‘meltdown’ so we can discuss it casually, knowing it is a normal part of the human experience.

Managing a meltdown

First up, we have to accept that:

a) meltdowns will happen and we typically won’t see them coming (i.e. an unexpected trigger is often what kicks them off).

b) whilst we can do a few things (listed below) to prevent them, shorten them or reduce their severity, sometimes we just have to ride them out. A meltdown is time-limited and this is important to remember in the context of managing them.

Consideration of the the anatomy of a meltdown gives us some points at which we can try and modify the experience.

The trigger

Meltdowns are triggered by something.

That ‘something’ is often out of our control and unpredictable.

But sometimes our triggers are things we know and do have some control over.

If you are a frequent meltdowner (I just made up a word), take a moment to analyse what sets them off. Are you always discovering assignments or work to be done that you haven’t noticed? Do you always get angry in traffic? Are there certain people who always trigger you off?

Some triggers are modifiable by changes in our pre-meltdown behaviour, namely we can reduce our exposure to these triggers.

Existing stress

Meltdowns are more likely to happen when our base level of stress is high.

Chronic stressors like illness, or financial problems or bad relationships can leave us vulnerable to being set off by additional or unexpected stressors.

Thus you owe it to your current and future self to manage, as best you can, the existing stressors in your life.

This might mean having to make some big changes in your life: getting treatment, changing jobs, getting out of bad relationships. Doing so will have positive consequences beyond that of simply reducing meltdowns.

Making significant changes in our life isn’t necessarily easy. Sometimes people using counselling to get a start on the process.

Physical experience

If you’ve ever seen someone (or been yourself) in a high level of distress, you know that it is a full body experience.

Changes to heart rate, breathing, perspiration, muscle tension, pain levels, gastrointestinal distress can all happen, reflecting the release of stress hormones and activation of the sympathetic nervous system.

Most of these changes are short-lived. For example, panic attacks which are highly physical usually last < 30 minutes.

There are some exercises that can help communicate to the body to exit the ‘freakout’ mode and enter a more restful/healing mode. They aren’t 100% successful, but they can help.

Breathing – breathe out for twice as long as you breathe in (1:2 ratio), breathe into the belly (tummy raises up), versus into the chest (shoulders lift). For some help with timing try https://www.calm.com/breathe or try the Breathe app by Reachout.

Progressive Muscle Relaxation – an exercise that involves tightening and then relaxing different muscle groups in the body. Helps you identify areas of tension and learn to release that tension. Often done using a guided audio file, until you know the process and can do it yourself.

Yoga – an ancient practice involving breathing, exercise and meditation. Try a yoga YouTube channel like Yoga with Adrienne this one, or an app like Down Dog. We even have a yoga teacher on our counselling team.

Changes in thinking

During a meltdown our thinking changes. The changes in thinking often further fuel the meltdown.

Our thinking becomes more negative: about self, others, the world, the future.

It becomes more distorted (i.e. you have more frequent or severe cognitive errors)

It becomes more ruminatory or obsessive – i.e. we get stuck on going over the same concept or event or fact again and again.

Sometimes the distress might be so high that we dissociate a bit (space out, go blank).

It is important therefore that we not make important decisions during a meltdown, as we are not perceiving and seeing the world accurately (with the exception of decisions to remove yourself from a stressful or dangerous situation).

In fact, the shifts in thinking that are associated with distress are so well known that ‘thinking’ is often the primary target in psychological therapies like Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT).

You can learn about CBT by doing an online course with a group like Mindspot or This Way Up. The more you learn to identify irrational thinking and modify it, the better you’ll get at countering the negative thinking patterns that can fuel a meltdown.

Meditation is another avenue that people often explore to help them develop a different relationship to their thoughts. Consider trying one of the popular meditation apps or doing an online course with a well-established meditation teacher.

Finally, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy is a style of therapy that combines mindfulness and psychological techniques to help people learn more about their thinking. Russ Harris and his book The Happiness Trap and companion app are a good starting point.

Overwhelming feelings/emotions

Strong emotions typically accompany a meltdown.

For me, anger tends to be the most common. For others it is anxiety or sadness or despair.

Emotions are intricately tied up with our physical sensations and our thinking. Thus the activities described above to modify either of those will often have an impact on our emotions.

In addition, there are strategies to directly target difficult emotions.

Self-soothing is about finding activities that relax you and elicit positive emotions. It might be as simple as a walk in the garden, a hot shower, playing music.

Grounding is about getting out of your head and reconnecting with the physical world. When we are highly distressed, we tend to disconnect from the physical world and get trapped in our thoughts and feelings. A simple example is the 5,4,3,2,1 exercise which requires you to:

- Name 5 things you can see.

- Name 4 things you can touch.

- Name 3 things you can hear.

- Name 2 things you can smell.

- Name 1 thing you can taste.

Learn more about grounding and self-soothing in this article.

Changes in behaviour

In the same way that we don’t tend to make good decisions during a tantrum, we also don’t tend to make good choices behaviourally either.

We might lash out at others. We might use drugs and alcohol to modify our experience. We might engage in other self-destructive behaviours.

These can sometimes have a short-term positive impact (hence why we do them), but they typically have negative medium to long-term consequences.

For example, I might have an anger meltdown and tell someone what I think about them. This might feel good in the short-term, but in the longer-term I feel regret and shame and I’ve also damaged the relationship.

You want to have at your disposal a small set of fallback behaviours that you can use during a meltdown to self-soothe but which don’t have negative longer-term consequences.

Maybe it is meditation. Maybe it is a luxurious jojoba bath. Maybe it is writing in a journal. You will need to experiment with different soothing behaviours to see what works for you.

The goal is to get to a point where you can identify that you’re having a meltdown and implement some simple and non-destructive behaviours, so that you don’t engage in behaviours that are destructive.

If you are having trouble thinking of things you could do, try this fun activities catalogue from the CCI.

Getting further help

Having a meltdown is not automatically a sign that you need further help.

We all have them and we all find ways to cope. It might be one of the suggestions above or something you find that works specifically for you.

But if you are experiencing frequent and/or severe episodes of emotional distress, it is worth having a chat to a/your GP. If you don’t have one, chat to one of ours.

It is also worth thinking about how you will respond when someone you know has a meltdown. How might you help them? You’ll gain insights into how you might help yourself in the process.