What kind of research is being done on programs that help students improve their academic performance AND wellbeing at the same time? I’m glad you asked! In this post I talk about a recent paper exploring an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy based intervention that seeks to help students improve BOTH their wellbeing and academic performance.

In some ways, the holy grail for ‘wellbeing’ focused interventions in higher education are those that simultaneously address wellbeing and study/academic performance. This gives students (and staff for that matter) the option to invest in a core set of practices that move them forwards in both domains. In a setting (academia) where few people report having spare time, investment in such practices would reflect an efficient allocation of time and attention.

With that in mind, I was pleased to find this recent study (2021) titled “Promoting university students’ well-being and studying with an acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT)-based intervention” by Nina Katajavuori, Kimmo Vehkalahti & Henna Asikainen.

Context

Back in 2017, Orygen published the “Under the Radar: the mental health of Australian university students” report. It expressed concern about the mental health of Australian university students. It pointed to the challenges of university life that place pressure of individual’s mental health (e.g. financial stress, lack of sleep, poor diet, balancing work and study responsibilities, living away from family and pressure to excel in the context of an increasingly competitive job market) and highlighted evidence that university students were, on average, more distressed than their non-student peers. As it turns out, both staff and students in universities are at risk of ill health.

This was not much of a surprise to those working and studying in the sector. University work/study is challenging and that challenge can become unmanaged stress, which can become burnout, which can become illness. Fortunately, mental health and wellbeing are now more of a focus within universities. Flinders (like many other universities) have started developing and actioning wellbeing strategies and are looking at what kinds of services, programs and resources can be distributed to support staff and students.

A standard approach is to provide individual support to those who are struggling (e.g. counselling, EAP) but this has limitations in that many who are struggling won’t reach out for such help. Thus, there is also interest in mental health and wellbeing promotion – getting tools, resources & practices into the hands of all students and staff through changes/additions to curriculum, university processes and community campaigns (e.g. Good Vibes Experiment).

Particularly desirable are tools/techniques/practices that have positive impacts on wellbeing AND productivity/performance. Staff and students are looking for help in both areas.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) as a contender

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is a form of psychotherapy developed by Steven Hayes and colleagues. ACT uses acceptance, mindfulness, values clarification and behaviour change strategies to increase psychological flexibility (PF) – “the ability to contact the present moment more fully as a conscious human being, and to change or persist in behavior when doing so serves valued ends”. Psychologically flexible people can better navigate the struggles of life because of more clearly defined vision (values, committed action) and capacity to make room for negative thoughts and feelings (mindfulness, acceptance, defusion).

PF is often visually represented as set of six sub-skills which can be trained. Don’t worry, I am not going to test you on these. The very short version is:

- Identify what is important to you (values)

- Outline specific steps to move meaningfully towards those values (committed action)

- Identify and make room for the difficult thoughts, feelings, memories, sensations and impulses that can show up when moving towards values (acceptance, defusion)

As Katajavuori et al., discuss, there is an ever-growing literature connecting improved PF to increased wellbeing, performance and work satisfaction. Participants in ACT interventions experience decreased depression, stress, anxiety, distress, and increased wellbeing, acceptance, engagement and life satisfaction.

Whilst the body of literature on ACT itself is large, the specifics of intervening with higher education students is preliminary, but hopeful. Other work by the study authors suggest PF predicts a number of positive study factors: positive emotions in learning, study progression, self-regulation and decreased procrastination.

The logic goes – if PF is trainable and positively impacts on both wellbeing and study outcomes, is PF (trained via ACT) a contender for the holy grail of wellbeing interventions in higher education?

The study

In fairness, the authors of the paper don’t use the term ‘holy grail’. I seem to have thrown that in there for dramatic effect.

They were interested however in “How Do Students’ Experience and Describe the Change in their Well-Being and Studying during the [ACT] Intervention Course?”

Perhaps an easier way to put that is “Can and ACT/PF-based intervention improve study and wellbeing outcomes in university students?”

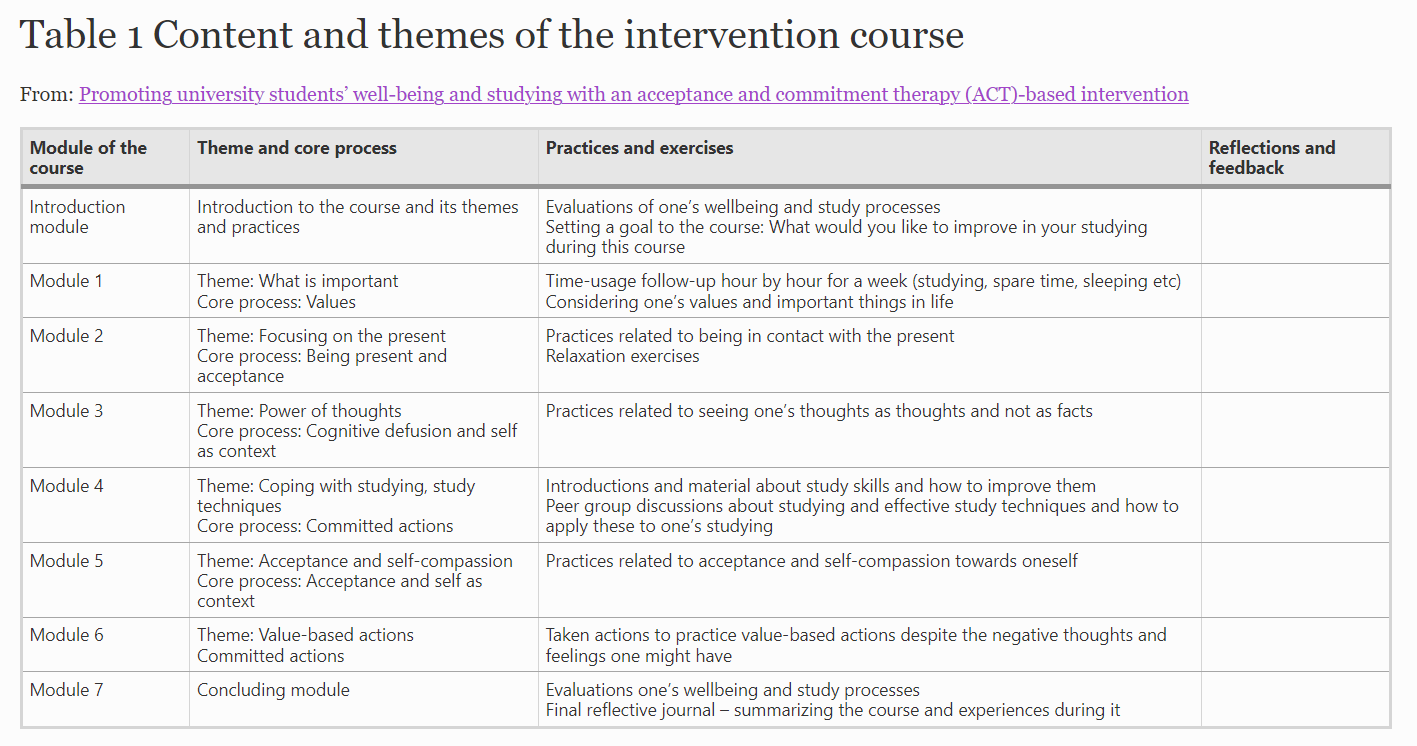

184 students from the University of Helsinki did a 7-week web-based ACT course. The course progressed week by week, with each week revolving around a specific PF theme and study processes. An overview of content is provided below. Sessions involved teaching on the theme, individual practices/ exercises and group discussions. Students also wrote and shared short reflective essays at the end of each week describing their efforts to implement the exercises.

Questionnaires measuring wellbeing, stress, organised studying, psychological flexibility were completed pre and post. Four likert items were used post course to assess students’ experience of the course.

Students wrote a reflective journal of 2-3 pages in the final week of course reflecting on their experiences of how the course affected their studying and wellbeing.

What they found

This was not a randomised controlled trial (RCT) so we don’t have a control or comparison group. We have one cohort being tracked over time.

Pre and post questionnaires showed modest improvements on all areas: wellbeing, stress, organised studying and psychological flexibility. That’s a good sign.

90% partly or totally agreed that they had a positive experience of the exercises. 82% partly or totally agreed the assignments were useful to them. 83% partly or totally agreed that they got new tools for managing their studies. 79% said it positively affected their studying.

Analysis of 97 reflective journal entries identified that 60%+ of participants felt they had increased wellbeing, increased self-knowledge, had greater awareness of their values, improved time management/ planning and a greater ability to accept negative thoughts and feelings. ~50% felt their thinking had changed and they were more mindfully present. 23% reported no dramatic change to wellbeing.

Whilst we can’t rule out other explanations (placebo, demand characteristics, spontaneous recovery), the results are logically consistent. Students showed and reported growth in areas that corresponded to the content taught. That deserves at least one 👍🏽

Implications

I like where this literature is headed, trying to find teachable practices that students can leverage for both wellbeing and academic improvement. With heavy study loads and most students navigating other commitments (work, family, health, caring), many don’t have time to invest in developing both areas separately.

Looking at the content of the program from the table above, that was achieved by the authors by interweaving the discussion of different aspects of PF with relevant study topics. For example, a discussion of values (what is important in life?) goes with a time audit (how am I spending my time?). A discussion of committed action includes specific study strategies a student could implement. Ideally, participants experience first-hand how the underlying concepts (mindfulness, defusion, acceptance, values etc) can be applied to both study and wellbeing outcomes.

The exploration of mindfulness-based therapies/strategies in this context is consistent with other work being done in this space including this mindfulness-based intervention for medical students and Monash’s mindfulness for academic success program, which as an aside is available here at Flinders. Mindfulness practices perform well across different areas of wellbeing, so it is reasonable to hypothesise they would provide study benefits. The program also includes self-compassion components which tend to resonate with students who can be highly self-critical.

ACT incorporates mindfulness, but in an expanded therapeutic model that also includes values, behaviour change & acceptance. Students can draw on values to frame their studies in the longer term, translate that into specific commitments in the present, and develop the tools to manage the difficult thoughts and feelings that arise in the short-term pursuit of those goals. The values work is central. As the authors say – “These studies support our results, which show that when students became conscious of their own values, it helped them to guide their life and actions in a meaningful way and guide them toward important things in their lives.” Values can be a steadying agent in the face of challenge and unpredictability.

There is still a long way to go in the development and evaluation of programs that jointly address wellbeing and academic outcomes, but this study and the work of that authorship group as a whole give me hope such programs are possible. I was also happy to see the program was web-based. As Flinders is a multi-campus University, we need program delivery methods that support inclusion across campuses and online.

The authors did explore, through qualitative analysis of those reporting minimal to no benefit, reasons why such a program wouldn’t work. The reasons are familiar to most of us – not enough time, already felt good, more severe mental health difficulties, difficulty understanding ACT principles and feeling burnt out. I believe these are addressable through different program formats (e.g. microlearning), facilitator education (strong grasp of ACT), clear referral pathways for those with severe struggles and gentle self-guided pacing of content delivery.

In the final words of the authors

“Our results show that students benefited from the course both in terms of studying and well-being. Developing students’ psychological flexibility had several benefits for studying and well-being. Thus, we suggest that in order to support successful studying in higher education, both student well-being and student study skills should be supported. We suggest that the ACT-based exercises would be worth to add to higher education curriculums.

If you are interested in this kind of stuff, we have two related programs here at Flinders – Mindfulness for Academic Success and Studyology, which is built on ACT principles.