Today Ben and I kicked off another Studyology V2 group.

For those that haven’t heard about the program, it is a 4-session small group program designed to equip students with the psychological skills necessary to tackle common study challenges: procrastination, low motivation, avoidance, study anxiety.

In today’s session we talked about a concept, ‘psychological flexibility‘, that I think is a very interesting concept, so I thought I’d post about it here on the blog.

I am going to try to explain what psychological flexibility is, and how you might start building it in your own life.

To understand psychological flexibility, first understand psychological inflexibility

You’ve probably heard the term that humans are ‘creatures of habit’, meaning we develop patterned ways of responding to certain situations.

When those patterned ways of responding to a situation are working for us, we don’t really think about it much. Our way of responding is ‘adaptive’.

But you probably have, much like me, some ways of responding to certain situations that are predictable, but not necessarily very helpful or consistent with the person you want to be, or the way you wish you would act.

Take the example of getting a bad mark on an assignment.

My usual response to that was get angry –> get sad –> think ‘I’m an idiot’ –> think ‘I’m not good enough to do this’ –> delete or discard the assignment –> stew in my own mental juices for a while –> distract myself with next assignment

I did this reliably when I got a bad mark.

The problem with that reaction however was that it didn’t help me be a better student, which was my goal. A better response would have included me reading the feedback, perhaps talking to the topic coordinator on what I could have done better and perhaps keeping some notes for things I could do in the next assignment.

Psychological inflexibility therefore is responding in predictable and unhelpful ways to situations, counter to your wishes or goals.

Psychological flexibility is therefore about creating space/room to respond in more adaptive and goal-consistent ways to things that happen in your life

Ok, that is way too long a heading.

But the essence of it is that psychological flexibility is about responding more appropriately in situations that would otherwise lead you to respond in an automatic and unhelpful way.

Instead of getting a bad assignment grade and reliably engaging in an unhelpful response, psychological flexibility is being able to punctuate that automatic set of responses, create an opportunity to respond in a different way and then respond in a way that is more consistent with your values or goals.

How do you build psychological flexibility?

As indicated above, the challenge of responding differently to situations that typically elicit an automatic and unhelpful response is that the typical response is ‘automatic’. Our response often feels like it unfolds without our awareness of it happening.

Building psychological flexibility therefore involves practising breaking into that automatic response.

How is that done?

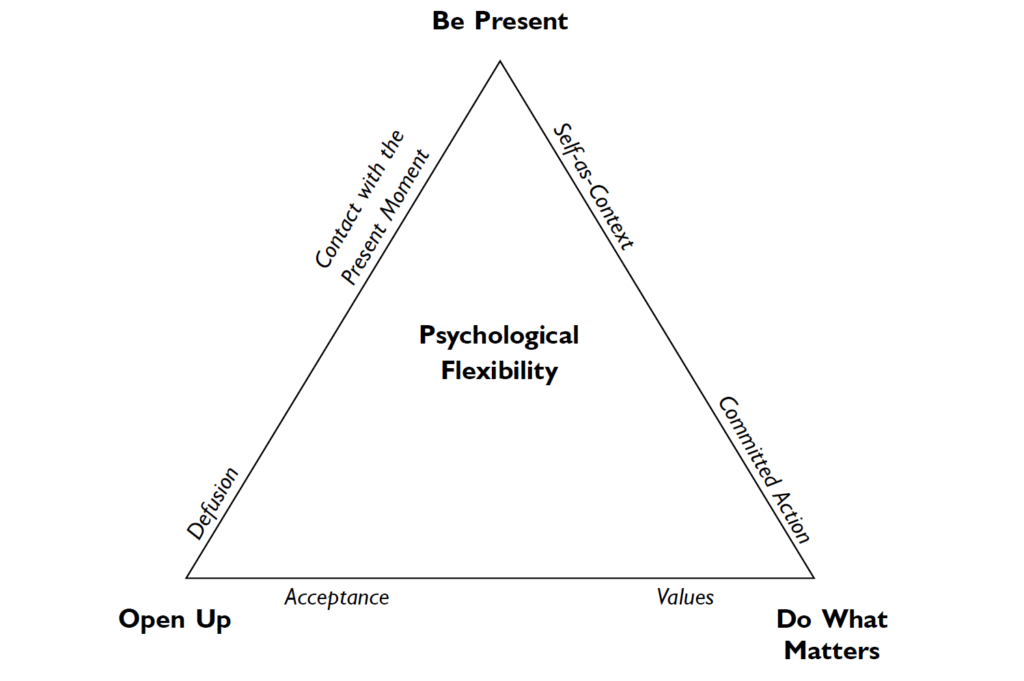

Three processes are important.

- Be present

- Open up

- Do what matters

These are reflected in the triflex diagram that ACT (Acceptance and Commitment Therapy) therapists use to describe the process to clients (see below).

I’ll try to describe these processes using the example of starting a difficult assignment, a time when lots of students notice their tendency to procrastinate.

Be present

Characteristic of responding automatically in different situations is being wrapped up in your own thoughts and thinking.

When this happens, we lose awareness of what is happening in the present moment. We lose the ability to notice objectively what is happening in our internal world because we are so wrapped up in it.

For example, when we start that difficult assignment, slowly the rest of the world fades out as we get wrapped up in feelings of anxiety, self-critical thoughts and worries. We get enveloped in a black cloud of past failures, future fears, doubts about our ability. It is not long before we’re so wrapped up in these internal experiences, that we lose track of what is happening around us and lose the ability to take stock of our situation and make good choices. We’re no longer sitting down to do an assignment. We’re sitting down to battle our internal experience.

Being present means pulling ourselves out of this black cloud and reconnecting with the present moment. There are a couple of ways to do this. One way is to do a grounding exercise which reconnects you with your five senses. The goal here is to interrupt the constant negative thinking by diverting attention to the full range of sensory experiences.

A second way (which I think is a good follow-up to the first) is to focus on noticing and categorising and naming the internal experiences you are having. For example, “I’m freaking out, and this sucks and its all going to go wrong again, and I am going to fail another assignment” instead becomes…

“I’m having the thoughts that this is going wrong again and I will fail the next assignment. I am also noticing some feelings consistent with ‘freaking out'”.

Now it might seem kinda silly to rephrase our internal experience in this way, but it is a way of viewing your internal experience with some distance. Rather than ‘being anxious’ you are noticing that you are ‘having the experience of anxiety’. To describe your experience in this way requires you to get enough distance from it that you are less likely to get wrapped up in it.

Open Up

When we sit down to start a difficult assignment, especially against a background of failed or late assignments, and we look inside to see how we are feeling, we often find content that we would label unpleasant. We might notice we are feeling anxious. We might notice that we are having lots of negative thoughts about ourselves or the situation. We might notice unpleasant physical sensations.

Common responses to this are to a) avoid these experiences by distracting ourselves or doing something else, b) get wrapped up in or keep going over these experiences in our head, or c) take actions to try and rid ourselves of these unpleasant experiences. In essence, our choices and behaviour become dictated by these experiences. We’re no longer responding to the actual situation we find ourselves in, we are responding to the internal experience we are having.

For example, when you start a difficult assignment, and get wrapped up in the negative self-talk that commonly goes with it, you start making decisions on the basis of the self-talk (e.g. admonishing yourself, avoiding the assignment, telling yourself you are stupid for feeling that way) instead of making choices and decisions specific to the assignment (e.g. doing the readings, taking notes, starting writing). You get wrapped up battling the wrong thing.

Opening up means taking a stance of acceptance towards whatever internal experiences show up without looking to modify those experiences, admonishing yourself for having those experiences or taking action to avoid them. You simply acknowledge their existence.

This might sound simple, but it isn’t necessarily as easy in practice. It is human nature to want to avoid or change unpleasant experiences, and this method works well when the source of the unpleasant experience is outside of us (e.g. getting out of the rain). The method isn’t as effective when the source of the unpleasant experience is inside of us (e.g. a feeling, memory, physical sensation). When we start an assignment, and get bombarded with negative feelings, memories, thoughts and sensations, it natural to want to modify or avoid those experiences. It’s very common to get totally wrapped up in doing so. To the point that the assignment is basically forgotten.

Rather than battling with those experiences, consider whether it is possible for you to be willing to have them, without intent to modify or change.

Instead you refocus your attention on ………..

Doing What Matters

If we are successful in punctuating our experience with moments of being present and open to experience, it means we are in a better position to make decisions that are in accordance with our goals and values.

In the case of starting an assignment, this means returning our attention to the assignment itself.

But ‘doing what matters’ isn’t just defined on the basis of the task at hand. ‘Do What Matters’ refers to acting in accordance with the person you want to be, rather than acting in response to the internal experience you are having.

So starting your assignment is not just the task itself. It is also:

- Working towards the goal of having a degree and changing your future

- Being a more conscientious person

- Being a studious person

- Showing others that you have the ability to do a degree

- Getting you closer to the kind of job you want

- [insert your own goal/value here]

You need to work out why study matters to you, and remind yourself of what it is you are actually working towards, so that you are willing to open yourself up to the difficulties and negative experiences of study. This is an important point. If you don’t have something important that you are working towards, what is the motivation to open yourself up to difficult internal experiences?

Takeaway points

Psychological flexibility is the ability to get in the present moment, be open to whatever shows up in terms of thoughts, feelings, memories and sensations, and take action in accordance with what is important to you.

In the study realm, this means:

- scheduling important study tasks into your calendar

- showing up and being present at the time when you need to start the task

- being open to, and willing to experience whatever thoughts, feelings, memories and sensations arise in the process

- motivating yourself to continue with the task by connecting the study task to the bigger picture of what is important to you

If you’ve developed quite an avoidant approach to your study, this will be a challenge.

Fortunately, this process is like a muscle. The more you use it, the stronger it gets.

Start by picking smaller more achievable tasks, then work your way up to scheduling study tasks that would once have had you running in the opposite direction.

Found this all a bit complex?

Don’t worry, this stuff takes a little digesting. Be sure to check out some of our other Studyology reflections (here, here and here), some of which are a little more accessible.

Stay tuned also for more Studyology V2 Updates.