The current Studyology V2 group had their last session on Tuesday (3rd September).

My sincere thanks to this pioneering group (like the first) who submitted themselves to be part of an ongoing trial into whether we can provide a study-focused group program for students who find themselves distressed at their lack of progress and engagement with their studies.

The feedback we (Ben and I) continue to get on this program is very positive. It is also very constructive. The group yesterday gave us many ideas on how to improve the program and for that we are truly grateful. I’ll talk at the end of this post about upcoming chances for you to do this program.

Many of the topics discussed in Studyology lend themselves well to blog posts. For example, I’ve written previously on the kinds of study avoidance cycles that can end up with you fearing your studies.

In that last session we covered some really interesting territory that I thought I’d share in this post. We focused on what students can do when they’ve got themselves so worked up about their study that they can’t engage with it directly.

First, some background

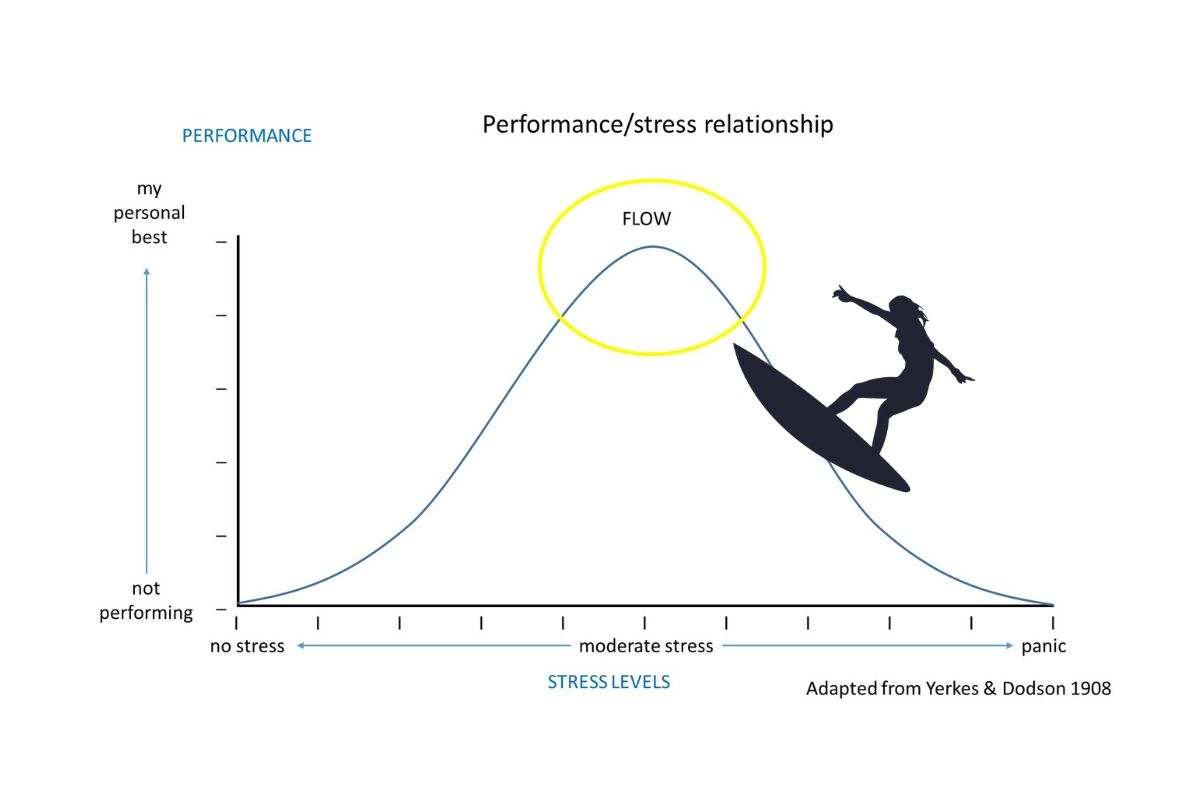

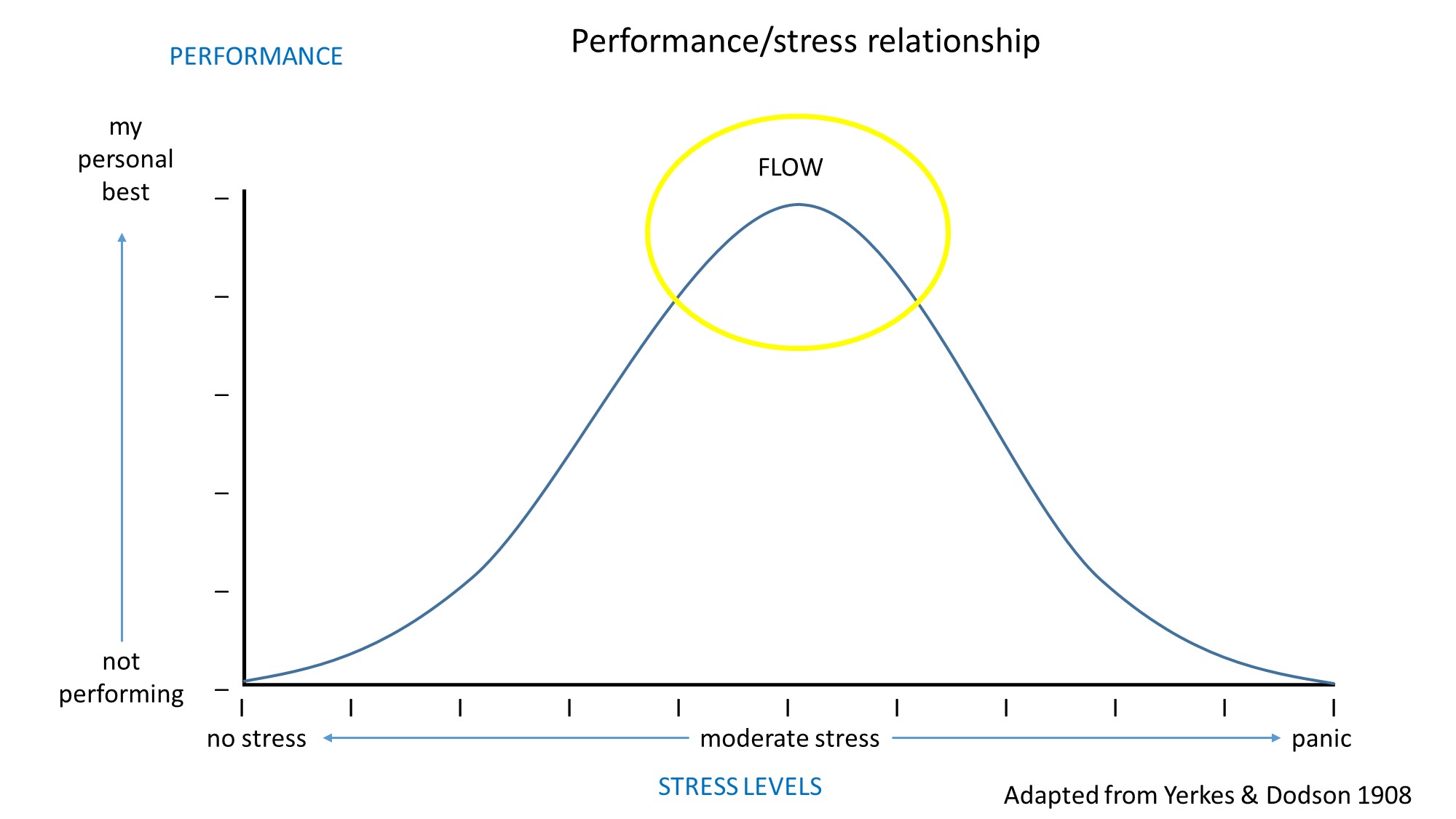

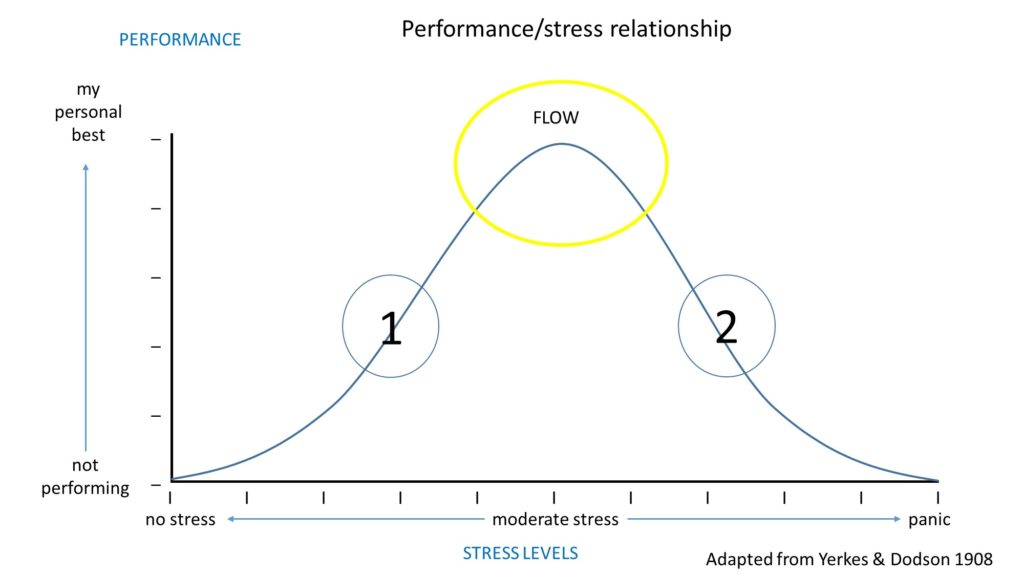

Roughly speaking, our stress level and our performance on challenging tasks like study are related as follows. With no stress, our performance is poor. We have no motivation, no real incentive or interest to perform. As our stress level increases, typically our performance starts to increase until we reach an ideal point (I’ve called it ‘flow’ in the diagram) at which we are performing at our best both creatively and productively. Beyond that stress level however, our performance starts to decrease. We get too overwrought to do good work.

Students often find themselves at one of two points on this curve. I’ve labelled these 1 and 2 on the diagram below.

At 1, students are typically contemplating or attempting to start a difficult assignment or study task. As the logistics or difficulties of the task dawn on them, they get increasingly stressed and uncomfortable. Whilst this is perfectly normal (learning new things is generally uncomfortable), students may interpret this as a bad sign and bail out. This is the procrastination point, where they distract themselves with other tasks, do something simpler, convince themselves they will be better at it tomorrow. I’ve covered previously some of the procrastination classics.

For students that struggle with procrastination, what we teach them in Studyology is to learn to observe and accept their thoughts and feelings at point 1, and practice working in the presence of those unpleasant thoughts and feelings. The more they practice working in this context, the more they train their mind to embrace those thoughts and feelings in the service of getting something important done (their studies).

At 2, students are typically starting or working on an assignment at the last minute and are feeling quite panicked. They can’t really escape or put the task off any longer, so instead they have to do their best with those strong negative feelings. This can mean that their work is of a lower quality and their brain learns over time to associate study with panic.

It was this situation that we focused on in the final Studyology session.

A potential focus for students in situation 2 is to ‘take the edge’ of those uncomfortable feelings, so that they can study at a stress level more closely approximating ‘flow’ than panic. It doesn’t mean trying to remove those uncomfortable feelings entirely as that internal battle commonly ends with the feelings being worse. Instead, it is about reducing them slightly in the service of being able to focus better on the task.

We talked about 3 main strategies/techniques that people can use the take the edge of uncomfortable feelings.

Breathing retraining

When we’re stressed or panicked, our breathing can become shallow and quickened – part of the nervous system’s response to threat. The good thing about the breath though is that you have some control over it and hence some degree of control over the nervous system (see caveats below).

Breathing retraining is simply the process of slowing down and deepening the breathing process, to signal to the mind and body that it can calm down.

These instructions from the CCI are pretty good.

This app from Reachout is also pretty good.

Don’t worry too much about finding the perfect breathing retraining exercise. As long as the exercise focuses on slowing the breath, deepening the breath (breathing from stomach, rather than chest) and exhalation longer than inhalation, you will get some benefits.

Important: We commonly see that when students learn the technique of breathing retraining people, they don’t actually use it until they are highly distressed – at which point, it is unlikely to be effective. For breathing retraining to be most impactful, you need to practice it regularly (i.e. daily), so you become familiar with the sensation of calm breathing. Then, when you need it, it will be more effective. Your mind and body will have memorised the feeling of calm breathing and you’ll be more likely to be able to engage in it when upset. It is also important to note that deliberate breathing may not change the anxious or stressed thoughts that accompany the nervous system arousal. Your body might relax a little, but you mind might still produce anxiety provoking thoughts.

Grounding

When we get stressed out, our brains typically get stuck in the past (regrets, things we did wrong) or the future (what if…. all the work we have to do).

Yet, where we really need to be if we are stressed about study is in the present moment, with the assignment or task at hand.

Grounding is any technique that gets you back in the present moment.

One of the simplest grounding techniques that I know is the 5,4,3,2,1 technique

Name 5 things that you can see

Name 4 things that you can touch

Name 3 things that you can hear

Name 2 things that you can smell

Name 1 thing that you can taste

It is described in a little more detail here.

At the end of using this strategy, you’d then return to the task at hand, focusing on what you need to do next.

Noticing and naming

When we are under stress, our thinking commonly falls into some set patterns (I call them our personal stories).

For example, when confronted with another last-minute assignment, a student might find themselves getting familiarly self-critical (“I always do this”, “I’m never going to learn”, “I’m an idiot”). This is their ‘failure story’ or their ‘not good enough story’.

Commonly we get wrapped up in these stories, going over all the examples in our lives where the story appears to be true. This is called ‘fusing’ with our thoughts. Where we assume that what we are thinking is an accurate description of how things actually are.

The problem is these stories are rarely fully nuanced. That student’s ‘failure story’ doesn’t include all the things they’ve successfully done in their lives. These stories may not be accurate representations of reality.

Therefore a simple strategy for defusing from these personal stories is to simply notice and name them. I had to do this this morning when some familiarly negative views about myself popped up for a visit. I named the personal story, and instead refocused my attention on what I needed to get done.

Practice, practice, practice

All three strategies require regular practice to become good at them.

This is an important point that requires further elaboration. I’ll use the example of exam anxiety to illustrate.

People with exam anxiety experience high levels of anxiety symptoms in the immediate lead-up to, and during exams. The level of anxiety they experience can derail their efforts to engage meaningfully with the exam itself and hence they run the risk of failing the exam.

One of the things we might teach students with anxiety is techniques like relaxation training, to help reduce some of the physical symptoms of anxiety.

However, if the student doesn’t practice those techniques before the exam, when the exam arrives and they get anxious, those relaxation techniques are unlikely to be of great benefit.

What the student needs to do instead is regularly practice those relaxation techniques at other times – when they are already relaxed, when they are doing some revision, when they are doing some self-testing. Practising these techniques helps train their mind to be able to reduce the physical symptoms of anxiety and achieve a more relaxed state.

Then, when the exam anxiety arises, they have a well practised procedure they can work through for dealing with it.

All of these techniques are there in the service of getting back to the task at hand

When confronted by a difficult task, with no room for further procrastination, it makes sense that stress and anxiety will emerge.

It is important that the techniques described above are not to be used to completely eliminate that stress and anxiety. In fact, you will probably find that if you use them to simply try and feel better, they may backfire.

The reality is that you need some stress and anxiety in order to be motivated to finish the task.

These techniques are simply to ‘take the edge’ off your stress level, so that you can re-engage with the task at hand. Some people try to use them as another avoidance technique (they get caught up in the battle of relaxing).

The ultimate goal is training your brain to work more frequently in the ‘flow’ zone, that zone of moderate stress, where you are at your most creative and productive.

Interested in Studyology?

Ben and I will be starting the next Studyology V2 program soon. If you are interested in participating in this 4-session program to learn more of the kinds of ideas discussed in this post, email me on gareth.furber@flinders.edu.au and I’ll add you to our distribution list to be contacted when the next program is being run.