Every year we review our statistics on the students we’ve seen and the problems/challenges they are dealing with.

Year in, year out, the most common reason students present to the counselling service is ‘anxiety‘. Furthermore, we hear from other students in other contexts (e.g. when we are giving presentations) that ‘anxiety‘ is one of the biggest challenges for students.

However, when we actually dig in further, we find that it is more nuanced than this. It is certainly true that a number of students develop anxiety, but many students who describe themselves as anxious are in fact stressed.

Whilst this might sound like an inconsequential distinction, it is actually very important, as there are different treatment and self-management implications depending on whether someone is experiencing stress or anxiety.

The similarities between anxiety and stress

One of the reasons why we tend to use the terms anxiety and stress interchangeably is that they can feel quite similar.

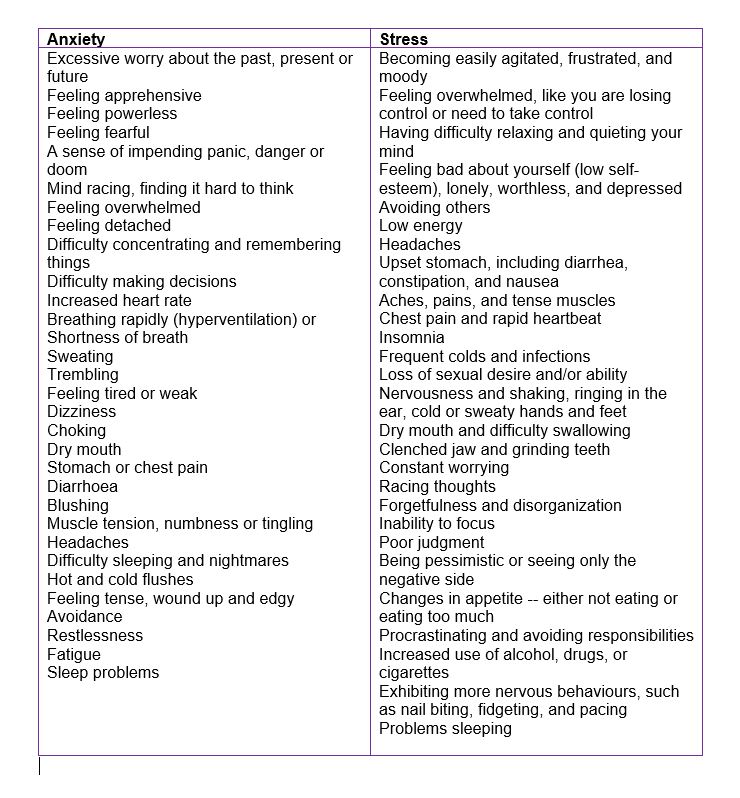

For example, compare these lists of symptoms:

You can see a lot of overlap between them, particularly in terms of physical symptoms, reflecting that similar physiological and psychological systems are activated in both (i.e. the sympathetic nervous system).

Stress and anxiety are also similar in that they can have a potent impact on our quality of life and our ability to function in the different areas of our life: study, work, family and friends.

One of the benefits of increased public education about anxiety is that people are now more willing to speak out when they are feeling stressed or anxious. However, we need to make a distinction between the two, so we can guide people more effectively to things that can help.

The difference between anxiety and stress

The primary difference between stress and anxiety is that stress is a response to a current/present stressful situation, whereas anxiety can be present regardless of whether the current situation would be considered stressful.

When we are stressed, we can usually attribute this to being overloaded in some way. Perhaps we feel like we have too much work to do and too little time. Or perhaps we are struggling to juggle study/work with other things like family, friends and health. Our stress makes sense, because we can specifically highlight the discrepancy between what we have to do (or feel we have to do) and our current mental, emotional and physical resources. When someone is stressed it is because the current demands on them are outstripping their actual or perceived ability to cope. Stress is common and not considered a mental disorder or illness.

When we are anxious though, it is not always easy to attribute this to being overloaded. Anxiety is more fear-based and relates to negative expectancies of what might happen. It commonly feels a little irrational, in that our level of fear about something exceeds how dangerous it actually is. There are common themes in terms of what people develop anxiety around. Phobias are irrational fears of specific objects or situations (e.g. snakes, heights). Panic disorder is the fear of the fear response itself. PTSD is the fear associated with memories and flashbacks of past traumatic events. Social phobia is the fear of negative evaluations by others. Generalised anxiety disorder is a collections of worries about a range of everyday situations. Whilst individuals with anxiety can definitely feel overwhelmed, their physical, emotional and mental reactions to what is going on for them is are far in excess of what you would expect. Individuals with anxiety become highly fearful and avoidant of objects or situations that actually pose little danger to them. Anxiety disorders are less common than stress and can (if severe enough) be considered a mental disorder or illness.

The problem with using these terms interchangeably (which I am as guilty of as anyone) is that people start confusing the two. They get stressed (and often quite seriously stressed) but mistake this for an anxiety disorder. There is a big difference between being stressed and having a diagnosable mental disorder – including how the conditions are managed.

What to do to manage stress

It is common and normal for university students to report stress. University study is intended to push you to your limits. In addition, students are often juggling other activities: work, family, health problems which means they feel ‘time poor’.

Some stress is good for us. In fact, putting yourself under some degree of stress is how you grow and get better. Consider those people who lift weights as an exercise. Lifting the weights puts stress on the muscles, which respond by growing bigger and stronger. Psychological stress pushes us to make changes in our life. It is a motivator. It is a source of energy from which to get better, smarter, faster, and more efficient.

Thus it is inevitable that you will feel stressed at some point during your studies. This typically feels like having too much to get done in the time available to you, or feeling like you can’t cope with the workload.

Tackling stress typically involves one of three things:

- Modify your workload – i.e. try to reduce the number of things competing for your attention. This might mean going part-time, or cutting back on other aspects of your life. This might sound like an overly simple method, but we see a lot of students who are simply trying to do too much. They are stressed because they have too much to do.

- Increase your coping capacity – i.e. make changes to how you go about your day to give you extra physical, mental or emotional resources to deal with your workload. This might include things like getting more sleep, improving your diet, getting more physical activity or getting more efficient at studying (using our evidence-based study tips). In fact, our self-care document was written to give students lots of different ideas for how they could build their coping capacity.

- Reframe the experience – i.e. shift how you view stress. Adopting a mindset that recognises that stress can actually provide the motivation and energy to get a lot done can mitigate some of its negative effects. The ABC has a nice article on this.

These strategies work well when we are dealing with common everyday stressors. An ‘everyday stressor’ is one that we would all accept is just a part of being a human being in a modern civilisation. This includes juggling work and family life. This includes the normal aspects of doing a degree (studying, exams, writing, public speaking). This includes the responsibilities of everyday life (paying bills, getting organised, helping family and friends, looking after your health). These are situations that we all need to learn how to manage.

These strategies don’t necessarily work as well if the types of stressors in your life are severe, chronic, inescapable or uncontrollable (e.g. exposure to domestic violence, frequent grief and loss, chronic severe illness, poverty). In these cases, it would be totally expected that the person would need to reach out for help (e.g. health and welfare services) in order to move forward.

What to do to manage anxiety

There are a couple of clues that you might be experiencing anxiety, rather than stress.

First, you might notice that the severity of your symptoms seem out of whack with the situation you are in. You might be terrified of giving presentations, even though everyone in the class is doing them. Perhaps you find you are constantly worried, even about things that don’t seem worth worrying about. Anxiety feels more like an illness (i.e. something is wrong with how I am thinking), whereas stress seems to make sense given the demands on you.

Second, you might find that your symptoms seem to coalesce around common anxiety themes:

- phobias – intense fear of specific objects or situations

- social phobia – intense fear of negative evaluations by others

- PTSD – fear symptoms based around previously experienced trauma

- panic disorder – fear of having panic attacks

- OCD – recurring unwanted thoughts, images, or impulses, as well as obsessions and repetitive rituals

- Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD) – uncontrollable worry about many different things

- find out more about different anxiety disorders – https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/anxiety-disorders

Even though the symptoms are similar as stress, you can see that there is a notable difference between feeling stressed (i.e. overloaded) versus anxious (i.e. fearful).

Anxiety can be helped through improving your self-care and coping strategies (mentioned above in the stress section), but typically those with anxiety disorders should seek some kind of formal assistance.

Treatments for anxiety are very effective but require specialist input. They involve learning specific strategies for managing fears, and commonly involved controlled exposure to the feared object/situation. For example, snake phobias are treated by getting the individual to approach increasingly more difficult situations involving snakes.

If you think you might have an anxiety disorder, there are some online sites like https://mindspot.org.au/ and https://www.mentalhealthonline.org.au/ and https://thiswayup.org.au/ for different types of anxiety. These sites use evidence-based methods to treat these disorders. They are low-cost or free. They are an excellent starting point for someone who might want to learn more about anxiety before reaching out for help.

You can also approach your GP and discuss the problems you have been having. They might then recommend seeing a psychologist or another mental health professional through a mental health care plan, or through a community agency. They may also consider medications depending on the nature of your symptoms. Typically the best results are achieved through a combination of treatments (e.g. psychological + medication) but this varies by individual.

Final thoughts

One of the benefits of increased public promotion around mental health issues is that people now have a broader vocabulary to describe the experiences they are having.

However it is important to be specific about our use of these different words.

One example is the difference between stress and anxiety.

Stress is the response to a stressful situation and is common to all of us. Stress is actually good for us in many situations. All of us have to learn strategies to manage stress.

However, anxiety relates to irrational fears and represents a disorder of thinking that typically needs to be formally addressed through treatment.

In understanding your emotional experience, can you distinguish which it is that you are experiencing?

Feel free to chat about this topic in the Wellbeing for Academic Success FLO topic