Chris Leow and James Hart are two nutrition and dietetic students who recently wrote a selection of nutrition blogs as part of the STEW program under Jayne Barbour’s supervision. I told them their posts could have a home on the Student Health and Wellbeing Blog and am very happy to include one of those posts below on salt (now where are my crisps?) See one of their previous efforts on sugar. If you want to write for the blog, see this post.

Salted – By James Hart, Nutritionist – Edited by Chris Leow

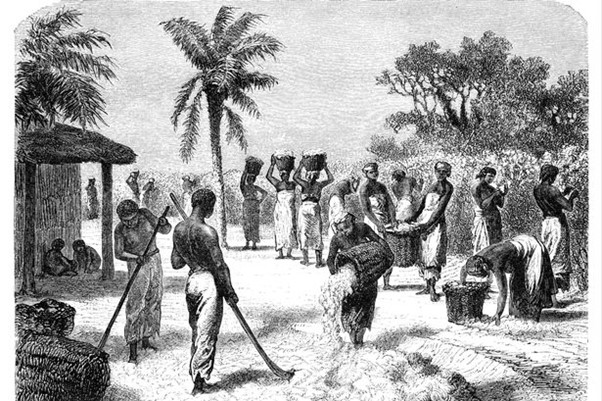

History

The little white imperishable substance, sodium, the eleventh element on the periodic table, was harvested in 6000 BC at Lake Yuncheng, China. It was the first commodity to be taxed (Ritz, 1996). The revenue from salts taxation allowed previous civilizations to finance wars, expeditions, and construction projects (Ritz, 1996). The Egyptians, one of the first civilisations to cultivate salt, which they called natron, used it to preserve mummies, meat, and fish (Ritz, 1996). Natrium, the Latin word for salt, was never more valuable than gold, yet its history would suggest otherwise.

Why is salt special?

Salt soaks up water, drying whatever it touches and hence slows the growth of bacteria. What we now call a preservative (Ritz, 1996) used to conserve and store perishables like meat and fish for long periods and was critical before refrigeration techniques (Ritz, 1996). Salt was crucial in a time where food had to be transported via horse wagon state-wide or via ships nationwide (Ritz, 1996). If history stresses the importance of using salt to preserve food, then why is there a health scare regarding its consumption? According to the ancient mythological Chinese Yellow Emperor Xuanyuan Huangdi, ‘if too much salt is ingested the pulse hardens, tears arise, and our complexion changes’ (Ritz, 1996). What the fictitious figure meant was that too much of a good thing can lead to unfavourable health outcomes.

Retention

Do you recall that I mentioned that salt holds water and is used for drying meat and fish for preservation? Well, it does the same in the human body if consumed in large amounts over time. Maybe not by drying our insides, but it can draw water and cause tension (Rakova et al., 2017). The human body can balance electrolytes such as potassium, calcium, and sodium to function normally (Rakova et al., 2017). Sodium supports muscle contractions, neurotransmission (the brain’s communication with other body parts) and maintaining fluid balance (Rakova et al., 2017). Too little sodium in the blood can cause hyponatraemia (hypo meaning low, natremia meaning salt). Symptoms include nausea, headaches, confusion, restlessness, irritability, muscle spasms and cramps. However, too much salt causes hypertension (hyper meaning high).

This tension (stress) occurs due to the narrowing of blood vessels, demanding our heart to pump harder to circulate blood from head to toe (Rakova et al., 2017). However, this increased force raises our blood pressure. Think of your downpipes clogged by leaves, which reduces water flow from rain on a stormy day. This seasonal annoyance leads to an overflow and water in unnecessary places. To ensure our pipes are clean (blood vessels) and water (blood) flows smoothly without pressure, we need to remove the leaves (reduce our salt intake) (Rakova et al., 2017).

How could the innocents of salt do this? Well, this ‘tension’ occurs because sodium holds water, and hence when consumed in excess, we produce less urine which paradoxically increases our blood volume. This increase in blood volume (amount of blood in the body) raises our blood pressure (Rakova et al., 2017). Buzzkill, right? Unfortunately, sodium is everywhere, from table salt, canned foods, packaged meats and most non-fresh food products. The question remains then, how much sodium is safe to eat, and which foods contain the most sodium?

Food Labels

Despite the negative depiction of salt, it is still a valuable nutrient in moderation. An iconic event in history saw experts in the field of medicine and nutrition came together in a white house conference in 1969 to discuss food, nutrition, and health (Kennedy & Dwyer 2020). The conference ended with the creation of what we now know as food labels and sowed the seed for dietary guidelines and nutrition labelling. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced that they will spend less time on food composition and more time on providing nutritional information on food products to inform the public to make healthier food choices (Kennedy & Dwyer 2020). This included foods with added nutrients, such as salt. Australia was not far behind, with the endorsement of the Australian Food Standards which passed the Food Authority Act in 1991 (Food Regulation Forum, 2015).

Who is currently responsible for food labelling in Australia? The Food Standards Australia and New Zealand (FSANZ) have developed standards for the two countries food industries. Food labels help us make informed decisions about the products we are buying and consuming. Health warnings and claims must be displayed on a food label and must have valid evidence to back them. It is reassuring that FSANZ has our best interest at heart, but there are over 20,000 food products on Woolworths and Coles shelves, making a simple shop stressful. We become decision fatigued, pulling a trolley or basket around the isles battling hunger while trying to maintain a budget and make healthier food choices. Furthermore, while food shopping, we hear sale prices and catchy tunes in the background compelling us to stay longer and buy more. Please note, never shop if you’re hungry as we tend to make irritational decisions and may purchase something high in energy with little nutritional value.

Solution

So, how can you reduce your salt intake? Choosing food products with less salt is the first step and knowing how to read a nutrition information panel can go a long way. The National Heart Foundation recommends consuming no more than 2000 mg of sodium per day, which equates to one tsp (5 grams) of salt (AGHE, 2015). That’s not much, but it is the amount necessary to reduce our risk of cardiovascular disease or cardiovascular accidents such as stroke or heart attack. Reducing sodium in our diet helps us maintain a normal blood pressure reading of 120/80mmHg.

Below is an example of a nutrition panel located on the back or side of a food product. The nutrition label includes a recommended serving size which changes depending on the product and could be measured in grams, slices, pieces, ounces, or numbers. For example, cereals usually have a serving size of 30g, while bread has a serving size of 1 slice and biscuits around 25g which will vary in number depending on the weight of the biscuit. Most nutritional panels contain a 100g quantity serving size for easy comparison between brands. Today it’s all about sodium and reducing the risk of hypertension by lowering salt in your diet. For best practice, aim for 120mg of sodium per 100g, or for good measure, 400mg per 100g. Remember, the goal is to consume less than < 2000mg of salt per day. Check out the nutrition panel below and become acquainted with how much sodium and other nutrients we should aim for.

An example of a low sodium product

How easy is it to reach 2000mg of sodium per day?

Let’s find out!

Take Gary’s daily food intake for example…

Breakfast

2x slices of white bread + 2 tsp of Dairy Soft butter = 270mg

½ cup of Kellogg’s Cornflakes = 340mg

200ml of orange juice = 0 mg

Sodium Total = 610mg

Morning Tea

1x banana = 0mg

Sausage roll = 962mg

600ml Farmers Union Iced Coffee = 270mg

Sodium Total = 1,232mg

As you can see, we have not even reached lunch and Gary has consumed 1842mg of sodium!

Lunch

1 x sandwich, made with 2x slices of white bread (270mg) + 1/3 tomato.

+ handful of ice-burg lettuce + 1x slice (30g) of coon cheese (230mg) +

30g of ham (350mg).

Sodium Total = 850mg

Afternoon Snack

200g of low-fat yoghurt (100mg) + a handful of strawberries

Sodium Total = 100mg

Dinner

1 cup of pasta (70mg) + 50g of shredded parmesan cheese (753mg)

+ ½ cup of Napolitano sauce (238mg).

Sodium Total = 1,061mg

Grand Sodium Total = 4,123 mg per day.

How many of us can relate to the food choices Gary makes? I know I do! Yet, Gary is consuming 4,123mg of sodium per day, double the recommended amount.

So, what can Gary do to reduce his sodium?

For Gary to make a change, he first needs to know where the sodium is coming from.

Where does sodium come from?

Foods High in Sodium

Tinned food

Baked beans, vegetables, pickles, seafood, olives, meats, legumes and more.

Packaged food

Cakes, biscuits, cereals, microwaved meals, noodles, chips, popcorn,

Condiments

Gravy, chutney, tomato sauce, mayonnaise, mustard, relish, salsa, creams and more.

Others

Bread, fish, smoked, cured, or salted meats, salted nuts, sardines, tuna, anchovies and more.

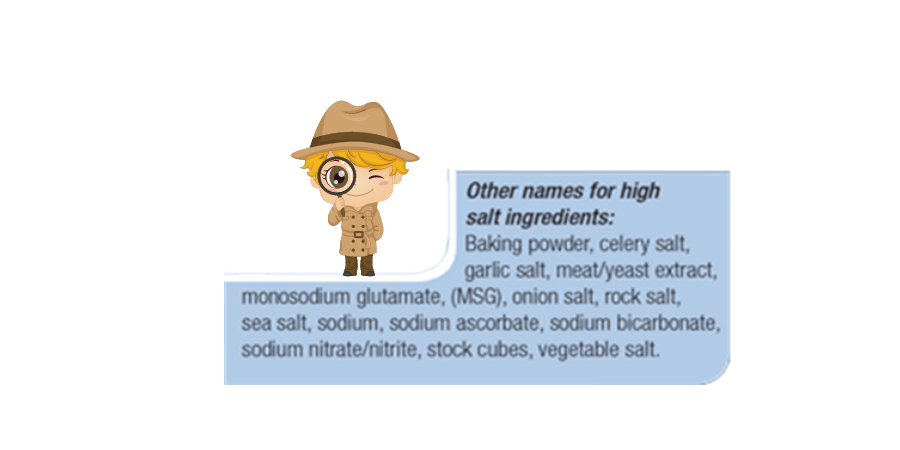

Therefore, it is important that we check the nutritional panel.

Foods Low in Sodium

Any fresh vegetables, such as tomatoes, cucumbers, carrots, pumpkin, and potatoes.

Any fruits, such as apples, oranges, and bananas.

Frozen, canned, or dried fruits with no added sugars.

Frozen vegetables without added butter or sauce

Wholegrains, like brown, wild rice, quinoa, or barley.

Whole-wheat or whole-grain pasta and couscous.

Check the nutrition label for the following:

Low sodium options

Unsalted popcorn or low-sodium chips and pretzels.

Tinned or packaged vegetables, fruits, meats, or seafood with the words reduced salt on the label (OK choice).

Tinned or packaged vegetables, fruits, meats, or seafood with low salt on the label (Good choice).

Tinned or packaged vegetables, fruits, meats, or seafood with no added salt on the label (Best choice).

Now that you have a better idea of where sodium comes from, lets reduce Gary’s sodium intake to under <2000 mg per day, he could try the following. In bold are the lower sodium changes.

Breakfast

1 x slice of white bread + 1 tsp of Olive Grove margarine = 135mg

1/3 cup of Uncle Toby’s rolled oats = 8 mg

½ cup of skim milk = 50 mg

200ml of orange juice = 0 mg

Sodium Total = 193 mg (Good)

Morning Tea

1x banana = 0mg

1 small tub of low-fat yoghurt = 30 mg

425 ml Rokeby Farms Chocolate Protein Smoothie = 102mg

Sodium Total = 132 mg

Lunch

Sandwich, made with 2x slices of white bread (270mg) + 1/3 tomato.

+ handful of ice-burg lettuce + 1x slice (30g) of cream cheese (50mg) +

30g of Deli fresh lean turkey (30mg).

Sodium Total = 350mg

Afternoon Snack

200g of low-fat yoghurt (100mg) + a handful of strawberries

Sodium Total = 100mg

Dinner

1 cup of pasta (70mg) + 50g of shredded Swiss cheese (213mg)

+ ½ cup of Passata sauce (120mg).

Sodium Total = (403mg)

Grand Total = 1,178 mg of sodium per day. <2000mg/day

Well done, Gary, by changing your type of cheese, cereal and tomato sauce to lower sodium options and by swapping your sausage roll for a low-fat yogurt and piece of fruit, we have lowered your sodium intake by a third.

Maybe you could do the same?

Summary

Sodium is an important nutrient like any other but should be consumed in moderation. As you witnessed from Gary’s diet, sodium is hidden in a variety of food products such as cheese, biscuits, some canned foods, sauces, pies, pasties and other processed foods and condiments. Overtime, our taste buds adjust to the amount of salt we are eating, which means we need more salt to detect its flavour. However, lowering the amount of sodium in our diet, by eating more fresh foods or choosing lower sodium packaged options, can increase our taste perception of the little white substance, meaning it takes less salt to notice its flavour. Remember, for good measure choose food products with <400mg per 100g or for best measure <120mg per 100g of sodium. Don’t be afraid to spend a few seconds reading the back of a nutritional panel, because eventually, the ‘pressure’ will fall right off! 😊

References

Australian Guide to Healthy Eating. (2015). Retrieved July 21, 2021, from the Australian Government & National Health and Medical Research Council. Web site: About the Australian Dietary Guidelines | Eat for Health

Factual Food Labels: A Closer Look at the History. (April 2018). Retrieved July 25, 2021, from the University of Texas at Austin, Department of Nutritional Sciences, College of Natural Sciences and School of Human Ecology. Web site: Factual Food Labels: A History of Food Labels (utexas.edu)

Food Regulation: History. (2015). Retrieved July 22, 2021, from the Australia and New Zealand Ministerial Forum on Food Regulation. Web site: Food Regulation – History

Kennedy, E & Dwyer, J. (2020). The 1969 White House Conference on Food, Nutrition and Health: 50 Years Later. Current Development in Nutrition, 4(6).

Rakova, N., Kitada, K., Lerchl, K., Dahlmann, A., Birukov, A., Daub, S., …Titze, J. (2017). Increased salt consumption induces body water conservation and decreases fluid intake. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 127(5), 1932-1934. Doi: 10.1172/JCI88530.

Ritz, E. (1996). The history of salt-aspects of interest to the nephrologist. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 11(6), retrieved from history of salt—aspects of interest to the nephrologist | Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation | Oxford Academic (flinders.edu.au)