So I read this article on the bus home the other day. It is called “Revisiting the Sustainable Happiness Model and Pie Chart: Can Happiness Be Successfully Pursued?” It is by Kennon Sheldon and Sonja Lyubomirsky.

In essence, the article explores to what extent we can increase our own happiness, separate from the effects of genetics and life situation. You see, in the same way that height and weight and physical attributes are governed by genetics and life situation, so are psychological attributes.

The question is then, how much control do we have over our psychological experience? Turns out that question is rather difficult to answer.

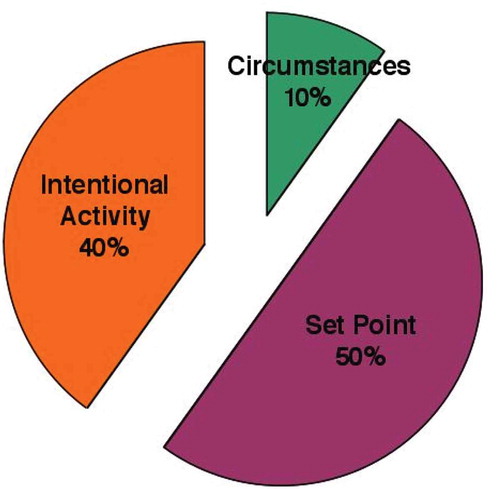

Back in 2005, Sheldon & Lyubormirsky (and colleague David Schkade) published an article in which they tried to answer that question in relation to happiness or subjective wellbeing (SWB). Drawing on a limited range of papers, they made the following estimates regarding the drivers of happiness. It became known as the happiness pie.

They identified 3 primary drivers of happiness – genetics (set point), life circumstances and intentional activities – and assigned to each an estimate of how influential each driver is in determining a person’s happiness.

They concluded that whilst a sizeable chunk of our happiness is determined by factors outside of our control (the set point idea that we all have a default happiness level, governed by genetics), there is still considerable potential for people to change their happiness through intentional activities, that is the choices you make about how you live your life. These changes could be lasting, not just short-term variations.

The article was instrumental in driving forward what we know today as Positive Psychology – the psychology of growth and improvement.

Since its publication, the article has received a lot of attention, including criticism. Researchers have challenged the conclusions of that paper, suggesting:

- some problems with the methodology that generated those estimates

- some problems with separating out genetics from life experiences and intentional behaviours (they are inextricably linked)

- there are many more life circumstances driving happiness that weren’t considered

- genetics probably explain more than 50% of variance

- the estimates were based on old papers and that there have been considerable changes in demographics and lifestyles since

Fundamentally, critics have argued that the 40% of variance attributed to intentional activities is likely to be a considerable over-estimate. Changing our happiness levels is not as within our control as we might think.

Sheldon and Lyubormirsky respond

The paper I read on the bus was the response of Sheldon and Lyubormirsky to these criticisms.

In essence they agreed with the criticisms, indicating that those estimates (the happiness pie) are probably out of date now.

They reiterated however that the fundamental idea of the original paper still stands. It is theoretically possible to influence our own happiness through intentional behaviours. They then go on to describe what current theories in happiness and wellbeing say about how that is done.

The practical takeaways from the paper

I believe that the fundamental reason to read papers or articles on wellbeing is to to extract from those papers knowledge that helps you understand the world and practical ideas you can experiment with in your own life. With this in mind, what could you take away from the recent paper by Sheldon and Lyubormirsky that might help you in your own efforts to improve your wellbeing?

1. Happiness fluctuates over the course of a day, week, month, year and lifetime. Some of the drivers of that fluctuation are out of your control. You therefore have permission to not hold yourself entirely responsible for your happiness.

2. The idea that we have a set point of happiness that we can’t change is likely incorrect. It is probably more accurate to say we have a range of potential happiness that we can move within and we have some capacity to move ourselves to the top of our happiness range.

3. Any shifts we experience in our happiness level as a result of intentional changes we make in our life are likely to be small, but still meaningful. Keep your expectations in check as you embark on your life improvement efforts.

4. If you are trying to improve your happiness, don’t focus on happiness itself, focus on goals that makes you, your life, or the life of those around you better. Pick goals that are meaningful to you. Be prepared to experiment with different goals and activities in the process to find those that are meaningful to you.

5. Be prepared to commit to ongoing efforts at self-improvement. Happiness is most likely to arise in the context of continually creating a steady flow of daily positive experiences that ‘interest, inspire, connect, and uplift’ you. It requires continual effort and change. Doing well –> feeling well.

6. Goals that revolve around a) getting better at something (competence), b) feeling more in control of your life (autonomy) and c) connecting with others (relatedness) are more likely to lead to happiness improvements.

7. When new positive things come into your life, there is a tendency to experience an initial increase in happiness, followed by a regression back to previous level of happiness. It is called hedonic adaptation and it helps explain why the accumulation of stuff doesn’t necessarily lead to lasting changes in happiness. When new things come into your life that increase your happiness you can sustain the effects of that by:

- regularly reminding yourself of the positive impact those things had on your life

- using that thing to create daily or weekly positive activities that elicit positive feelings/thoughts and behaviors (e.g. use that new phone to set up a regular practice of reading)

- use that thing to reorganise your life in a way that is more consistent with your goals and values (e.g. when you move into a new house, set up a regular social event at that place)

- regularly express gratitude for the thing that has come into your life

As the authors say “happiness can be successfully pursued, but it is not ‘easy'”.

Use your life to chase important activities and do so in a varied and changing manner. This is more likely to create a ‘steady flow of engaging, satisfying, connecting and uplifting positive experiences’ – increasing the likelihood that you can make sustained changes to your happiness.