I take a look at some research by Hobbs, Jelbert, Santos, and Hood (2024) that finds that the benefits of happiness courses are only maintained when participants continue to use the happiness strategies they learn in those courses.

This paper caught my attention earlier this year and I’ve been keen to discuss it on the blog.

It demonstrates a simple but important concept, namely that to build and sustain positive changes in one’s mental health, requires long-term habit change.

Let’s take a look.

Hobbs, Jelbert, Santos and Hood (2024) conducted a long-term analysis of the benefits university students received from a psychoeducational course called the “Science of Happiness (SOH)”. These were students at the University of Bristol.

SOH is based on the highly popular Yale course – Psychology and the Good Life. It covers topics like the nature of happiness, the role of biology, environment & genes in happiness, common cognitive biases, impact of distorted reasoning, important brain mechanisms, the art of problem-solving, and the importance of social connection. The course involves recorded lectures, live sessions, small group meetings, weekly reflective journaling, personal experimentation with happiness ‘hacks’ and a group project, all delivered over an 8-week period.

Course like SOH are popular because mental health concerns constitute the greatest burden of disease in young people, including those studying at university. These courses play a preventative role – equipping students with the knowledge and skills needed to look after their mental health.

Previous research has shown that these kinds of courses lead to small but meaningful improvements in wellbeing, anxiety and loneliness, and that students rate such courses highly. But something many of us (who deliver these kinds of programs) fear is whether there is any long-term positive impact. Do the benefits of the course cease when the course ends?

To try and answer this question, the authors contacted 905 students who had previously completed the 8-week program 1-2 years earlier, and asked them about their wellbeing, anxiety and loneliness.

225 students responded and provided a long-term follow-up measurement point.

When they look at the group as a whole (all 225), they found only weak evidence that the benefits of the course were maintained. Specifically, there remained a slight improvement in wellbeing.

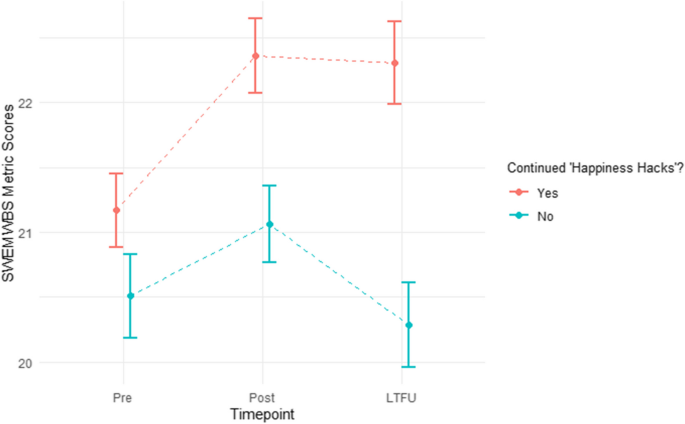

But when they compared students who reported continuing to use some of the happiness hacks they had learned (n=113) to those that did not, the differences were clearer. Those students who kept using the happiness techniques they had learned, maintained the improvements they showed just after the course. For the others, the benefits were lost at follow-up. You can see this in the following chart, looking at wellbeing scores.

This finding suggests a similar reality for positive mental health interventions as for dietary and physical activity interventions. For the benefits to be maintained over an extended period of time, the individual needs to continue using the strategies.

Another way to put it is that to achieve long-term change in mental health requires long-term habit change.

Now of course this raises the question as to why some students continued to use the practices (‘hacks’) whilst others did not. Additional research will be needed to answer this question.

But you can use this as a point of reflection in your own life. Have you ever started a healthy, beneficial practice, only to cease it later? What were the reasons? Conversely, what healthy practices have you been able to maintain long-term? What has made this possible?

As a mental health professional involved in delivering these courses and programs, this study underscores the initial benefits such programs can provide in improving participants’ mental health. However, it also highlights the need for additional support initiatives to help participants maintain these improvements over the long term once the course concludes.

For example, here at Flinders we have the Be Well Plan, an evidence-based psychoeducational program much like SOH. We know that this program produces short-term improvements in mental health and wellbeing. But now I am thinking about how we could support students to maintain those gains over the long-term.

In conclusion, it appears that in the area of mental health, long-term improvements in mental health require long-term changes to behaviour. So, if you find a mental health strategy that helps, think about how to embed it into your everyday life, so it becomes a part of the fabric of the days, weeks, months and years ahead.

Study: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10734-024-01202-4