Want to learn better? Want to make that brain of yours an unparalleled machine of learning? In this article we explore distributed practice, retrieval practice, and interleaving, techniques designed to enhance memory retention, recall, and comprehension for lasting knowledge.

When you start teaching, you also get more interested in how people learn. That has resulted in me taking an interest in learning science – the science of how people learn.

Most of what I learn about learning ends up in my ‘Evidence-based study, exam preparation and writing tips‘ document. You can burn your eyeballs with said document here.

However, inspired by this series of papers, I thought I’d use this post to explore 3 primary learning strategies that you can start using with your studies.

Distributed practice

Say you had 6 hours to put towards studying for an exam.

Distributed practice research would suggest it is better to do 6 x 1-hour sessions, with days in-between, rather than a single six-hour block.

Basically, spread out your work over days and weeks, versus cramming it all into a single block. This applies to verbal learning (e.g. remembering facts), problem-solving (e.g. doing puzzles) and skill acquisition.

So why is this the case? There are a few proposed mechanisms.

First, when we stimulate our mind with new information, we get diminishing returns (in terms of stimulation) by visiting the same material repeatedly in a single sitting. If we space it out though, each time we get a level of stimulation similar to the original presentation. Brain activity lessens with each practice when crammed together.

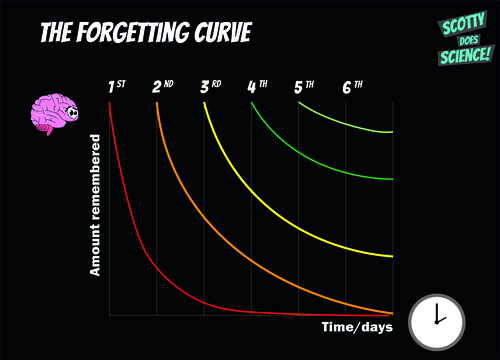

Distributed practice also more effectively slows the forgetting curve by regularly reinforcing content.

Something which I found interesting was that when we distribute learning over days and weeks, initially the information is held in one memory circuit (connected to the experience of learning), but when we revisit it repeatedly, it moves into another memory circuit (focused on learning facts). It moves from episodic memory to semantic memory and semantic memory is more robust in the longer-term.

I asked ChatGPT for some practical examples of what distributed practice looks like for your average student. ChatGPT took a while (it must get lots of questions everyday), but provided some nice examples:

- Flashcards: Review flashcards containing key concepts and definitions regularly over several days or weeks.

- Study Sessions: Divide your study material into smaller chunks and study different chunks on different days.

- Homework Completion: Complete assignments in smaller portions over multiple days instead of cramming all at once.

- Reading Assignments: Read course materials in advance and revisit them periodically before exams.

- Practice Problems: Solve practice problems from various topics, returning to them periodically to reinforce understanding.

- Revisiting Notes: Review lecture notes after each class, then revisit them periodically before exams.

- Quizzes and Tests: Take practice quizzes or tests on different topics, spacing them out over time.

- Language Learning: Practice vocabulary or grammar rules over multiple days instead of in one session.

- Essay Writing: Break down essay writing into researching, outlining, drafting, and revising stages spread across days.

- Online Learning: Utilize online platforms that offer spaced repetition techniques for learning languages, coding, or other subjects.

- Review Sessions: Organize study groups to review and discuss topics from class sessions at regular intervals.

- Digital Tools: Use apps or software that incorporate spaced repetition, such as Anki or Quizlet.

Retrieval practice

Retrieval practice involves repeatedly bringing to mind previously studied information. Read a book, put it down, and then see how much of it can you remember.

Often, we aren’t required to bring learning to mind until we are in the exam room, answering questions in a high stakes test. So, we spend too much time studying content, but not testing ourselves on it.

Retrieval practice is giving yourself lots of low-stakes and no-stakes tests whilst you are learning stuff.

There are a number of ways that we can test ourselves whilst we are learning: quizzes, flashcards, doing old exams, answering questions at the end of each chapter of learning, concept mapping from memory. All constitute very active, effortful ways of engaging with the material and are much better than simply re-reading.

Generally, free recall (i.e. trying to remember as much as you can of something you read, unaided) is better than recognition recall (e.g. seeing the answer in a multiple choice), but both are valuable. In one case you might be responding to old open-ended exam questions. In the other you are doing multiple choice quizzes.

Retrieval practice strengthens a memory circuit by requiring us to access the information from long-term memory. Memory isn’t just about studying a topic, it is also about the capacity to retrieve that information as necessary. When combined with feedback (did you remember correctly?), repetition (i.e. distributed practice), and opportunities for correction/improvement, it is an incredibly powerful tool for learning information long-term.

Something cool which I hadn’t come across before was ‘pre-tests’. Basically, do a relevant quiz BEFORE you start learning the content. It supposedly primes the retrieval of existing knowledge, preparing you to learn the most important parts of what is subsequently presented.

Interleaving

Ok, so the final strategy.

Interleaving is a study technique that involves mixing different topics or subjects during study sessions, rather than focusing on one topic at a time.

As far as I can gather, it is useful when the topics you need to study are related but distinct.

By mixing up these topics, it forces your brain to reconcile differences and similarities. It requires you to learn to discriminate between the different areas. It may also support the learning of the interconnections between the different topics.

Another way it might work is that our attention fades quicker when we are studying a single topic area for an extended period. Mixing topics may help keep things fresh.

ChatGPT helped me out again here by providing examples of interleaving in different topic areas:

- Mathematics and Physics Practice: Instead of completing all math problems and then moving to physics problems, interleave the two subjects. This helps develop the ability to differentiate between problem types and choose the appropriate solution strategy.

- Language Learning: If you’re learning multiple languages, practice vocabulary and grammar for each language in the same session. This challenges your brain to switch between different language structures, enhancing your overall language skills.

- History Topics: When studying history, interleave different historical periods or events. This helps you draw connections between different eras and develop a more holistic understanding of historical context.

- Science Concepts: If you’re studying different scientific theories or concepts, alternate between them in your study session. This aids in recognizing patterns and similarities among different theories.

- Literature Analysis: If you have to analyze multiple literary works, interleave the analysis of different texts. This sharpens your critical thinking skills as you compare and contrast different themes, styles, and literary techniques.

- Problem-Solving in Computer Science: Interleave coding problems of various difficulty levels and from different programming languages. This improves your adaptability and problem-solving skills in coding.

- Music Theory: When learning music theory, alternate between practicing different scales, chords, and musical compositions. This helps you integrate various musical concepts more effectively.

- Medical Studies: For medical students, interleaving could involve studying different medical cases or diseases in a single session. This improves diagnostic skills and the ability to differentiate between similar symptoms.

- Economics Principles: When studying economics, mix up concepts like supply and demand, market structures, and economic policies in your study session. This strengthens your ability to apply economic principles to real-world scenarios.

- Psychology Experiments: When learning about different psychology experiments, interleave the details of each study. This aids in recognizing common research methodologies and understanding the nuances of each experiment’s findings.

My work doesn’t involve learning, so much as progressing different projects. In that context, I find there are limits to how many projects I can work on in a given day, that is, how many different projects I can interleave. Generally, I limit myself to 2 projects in a single day, so that I don’t spend large amounts of time switching between them.

If you are going to switch between topics in a single study session, it is important to be organised and have the content you are going to work on already prepared before you start, so the switching is efficient and quick.

Final thoughts

When I was studying my degree, I did a lot of last minute work, just like everyone else. And generally it worked OK. I got decent grades and made it through.

In hindsight, though I realise there is a difference between studying to pass a test/get a good grade on an essay versus studying to truly learn the underlying material.

Most of what I studied I forgot, because I used strategies that worked in the short-term but weren’t optimised for long-term retention.

The 3 strategies described above are optimised for long-term retention. It means that in the short-term they can actually feel harder than cramming for individual topics. It is often why high quality learning strategies are called ‘desirable difficulties’, capturing their effectiveness but also their difficulty.

The fact that they feel harder is probably one reason why people don’t use them. With that in mind, instead of expecting yourself to transform your study habits, see if you can find one topic or one exam/essay where you are willing to try something different. A topic where you visit the content repeatedly over the course of the semester (distributed practice), test yourself with flashcards (retrieval practice) and juggle different parts of the topic on a given study day (interleaving). Compare what the experience is like to your normal study patterns.

And if you need help? Well, I was just chatting online with one of the learning advisors from SLSS and they know this stuff well. It is their bread and butter. Consider visiting the Learning Lounge if you want some tips on how to use these strategies in your own study routines.